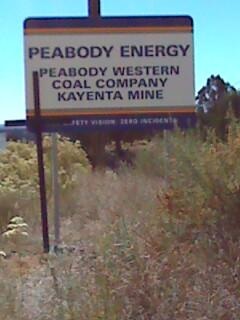

As the Labor Department made an unprecedented move yesterday to file a court injunction to shut down a hazardous Massey Energy coal mine in eastern Kentucky for a "a pattern of violations," concerned residents and activists constructed symbolic black crosses in front of the Navajo Nation's own Kayenta Mine, which was named last spring as one of the most dangerous mines in the nation.

Launched in the southern Illinois coalfields, the Black Cross Alliance movement has called attention to the growing deathtoll from coal mining and burning across the Midwest, Appalachia and Western coal regions.

The action came on the heels of a district court ruling last week to suspend a permit for the expansion of the nearby Navajo Mine near Farmington, New Mexico.

The Kayenta Mine itself may be operating completely in violation, according to a new complaint filed in court by several Navajo and environmental organizations last month, which noted that the Office of Surface Mining may not have even followed proper strip mine permitting procedure.

After nearly 40 years of devastating operation on the Navajo Nation, the dwindling Peabody Kayenta Mine has been cited by MSHA for faulty equipment, accumulation of combustible materials and inadequate workplace safety. For area residents with the Black Cross Alliance, who posted large black crosses across the coalfields on the reservation, the mine also represents a reckless use of scarce water resources, costly and deadly contamination of watersheds, the destruction of sacred lands, and a hinderance to the development of any sustainable economic development in the area.

Along with leaving behind sacred eagle feathers, the black crosses included the message:

You shall not press upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns.

You shall not crucify us any longer upon a cross of coal.

Last month, the New York Times ran a feature story on the growing Navajo movement to move away from the coal mines, which have dominated the region for decades. Citing the drastically reduced income from the mines, coupled with the growing health care and environmental damages and costs, Navajo residents have called for an increased investment in new power sources. The Times explored the impact of the mines on the residents:

"Quite a few of my relatives have made a good living working for the coal mine, but a lot of them are beginning to have health problems," he said. "I don't know how it's going to affect me."

One of those relatives is Daniel Benally, 73, who says he lives with shortness of breath after working for the Black Mesa mine in the same area for 35 years as a heavy equipment operator. Coal provided for his family, including 15 children from two marriages, but he said he now believed that the job was not worth the health and environmental problems.

"There's no equity between benefit and damage," he said in Navajo through a translator.

The Navajo Nation became the first Native reservation to set up a Green Jobs commission last year.

Last spring, Black Mesa area resident Marshall Johnson, director of the To Nizhoni Ani organization, wrote an editorial in the Arizona Republic calling for a just transition to clean energy development. Johnson concluded:

But the safety concerns of the Kayenta Mine go beyond the dangers of tunnel collapse or explosion. In 1967, the Peabody coal company began operating two strip mines on top of Black Mesa: the Kayenta and Black Mesa mines.

On average, they have used more than a billion gallons of our pristine water each year to wash and transport the coal, water down roads and clean their industrial facilities. The Navajo Aquifer, our sole source of drinking water in the region, has seen major decreases in water levels and shows signs of structural damage.

What water remains underground after their excessive use is threatened by leaking waste ponds.

Coal waste contains heavy metals, such as mercury, lead, thallium and arsenic, which can cause birth defects and nervous- and reproductive-system disorders. And as community residents have complained for years, the 250 waste ponds in the area regularly overflow and appear to be leaking in some locations.

Yesterday, Navajo activists declared their intent to continue their vigil across the region.