Foundations: Oscar Wilde and the Origins of Photo Copyright

In 1882 a 27-year-old Oscar Wilde arrived in New York City. Wilde's best-known works, The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest, were still years away, but Wilde had an aptitude for notoriety. Witty, flamboyant, and aggressively charming, he became an overnight cultural sensation among the city's social elite. Napoleon Sarony, a celebrity photographer known for his theatrical and flattering style of portraiture, solicited Wilde for a sitting.

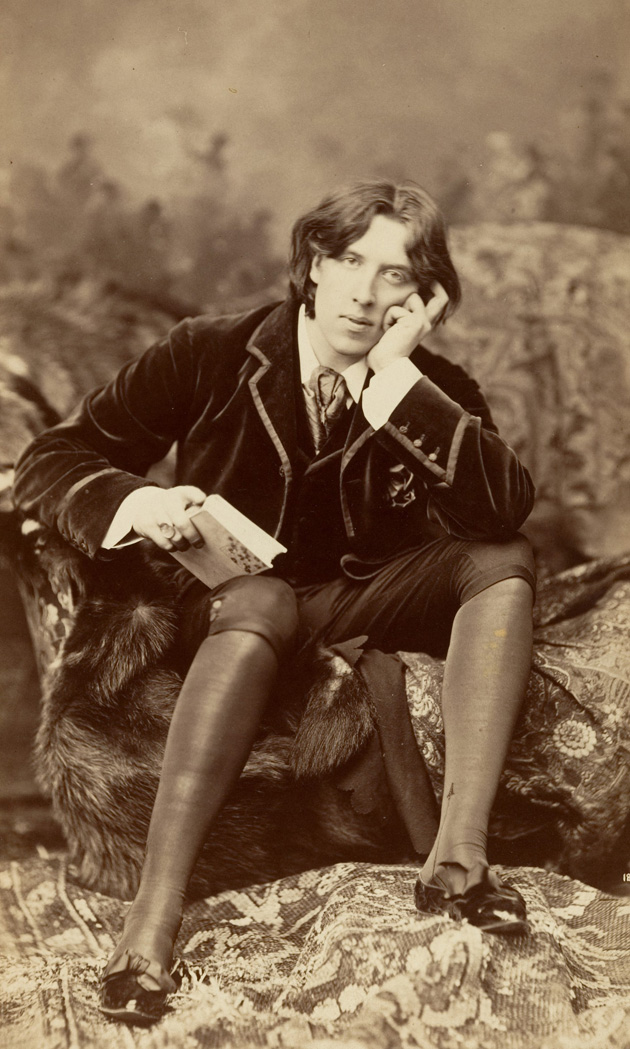

Sarony crafted twenty-seven portraits of Wilde in an array of ensembles, ranging from dignified to outlandish. The eighteenth photograph featured a contemplative Wilde sitting on a fur-draped chaise lounge donning a piped velvet jacket, silk stockings, and glossy patent-leather shoes. Soon after, New York department store Ehrich Brothers began using a copy of the photo to promote a line of hats. Sarony sued for copyright infringement.

The Copyright Act of 1865 explicitly extended copyright protection to the nascent medium of photography. However, the idea that "reproductions of the exact features of some natural object" could qualify as original creative works within the meaning of copyright law remained controversial. The Supreme Court noted that Sarony had intentionally crafted his photograph by arranging the background and by dressing, posing, and coaching his model. The Court found that the control Sarony exercised over his subject rendered him the "author" of an "original work of art" meriting full copyright protections.

Enter Richard Prince, "Appropriation Artist"

Fast forward 132 years to modern-day New York. Richard Prince, an "appropriation artist" well-known in creative spheres, is showing blown-up screen shots from his Instagram feed in renowned Manhattan galleries. The contemporary counterparts of Wilde's Gilded Age fan base buy the inkjet-on-canvas prints for upwards of $100,000. The original snappers hear through the proverbial grapevine that their filtered selfies are featured in high-end art shows.

Copyright law has evolved markedly in the century separating Richard Prince from Napoleon Sarony. On the shoulders of Andy Warhol and Jeff Koons, Prince has made a decades-long career selling slightly altered versions of other people's images. He evades copyright infringement liability through legal principles that allow certain "transformative works" to make use of copyright-protected materials without the owner's consent. Broadly, a transformative "fair use" alters or recontextualizes the original work for the purpose of commentary, criticism, or parody. All of the pieces in the Instagram-based New Portraits series include Prince's own original "comment" within the captured frame, submitted via his Instagram handle, "richardprince1234". He also enlarges the images and moves them from digital to print media. The original photos, which cover most of the space on the printed canvases, remain otherwise untouched.

Donald Graham, a career photographer whose portrait of a Rastafarian man was involuntarily featured in New Portraits, is not impressed. In a complaint filed in federal court this January, Graham calls Prince's work a "blatant disregard of copyright law". Graham's suit challenges whether Prince's transformations are sufficient to trigger "fair use" protection.

Who owns your Instagram photos?

The simple answer is "you do," but your effective rights may be extremely narrow.

The Copyright Act grants authors the exclusive right to copy and distribute their original creative works. Copyright owners also have the right to control any "derivative works" based on or including their protected materials. However, in the modern internet era, bedrock principles of creative protection are routinely challenged. Resulting cases like Graham v. Prince are defining the contours of digital age copyright law.

Instagram's Terms of Use indicate that posting to the site implies the poster (1) owns the content or otherwise has a right to share it, and (2) grants Instagram a license to use the content in accordance with site policies. Individual Instagram users have no legal right to make use of one another's original content without permission.

Unlike Facebook, Twitter, and other social media sites, Instagram has no built-in functionality that enables sharing or reposting. Nonetheless, content sharing on Instagram is ubiquitous. Cropped screen-grabs and applications like PhotoRepost and Regram make it easy to share other users' images. Unlike re-Tweets and re-Pins, these unendorsed reposts often omit attribution. Posters technically retain an exclusive right to copy and distribute original images, but these rights are routinely infringed and nearly impossible to enforce.

As with any image, substantially transformative uses of protected Instagram content are sheltered by the fair use exception to copyright infringement. For Instagram posters, exact copies (in the form of reposts) are also effectively permitted. If minimally transformed screenshots are legitimized as a fair use, unwary Instagram posters may retain only nominal copyright protection. Artists, photographers, and other original content generators face a dilemma as they seek to simultaneously promote and protect their work.

Taking preventative steps to protect original images can bolster an owner's copyright position. Watermarking photographs decreases the likelihood of unattributed reproduction, and providing a notice of copyright protection can strengthen potential legal claims. Those seeking to make use of the plethora of crowd-sourced content available on social media can also benefit from anticipatory measures. Securing an owner's permission to use an image is an absolute defense to an accusation of copyright infringement. Attributing a photo to the original source or including a disclaimer in a derivative work may decrease the likelihood of a copyright challenge.

While helpful, watermarks, notices, attributions, and disclaimers do not prove or disprove a copyright violation. The context in which appropriated content is redeployed also has important implications. If a protected image is used without permission for a commercial purpose, such as promoting a line of hats, this is almost certainly copyright infringement. An attribution or disclaimer will not rescue the infringer from liability. Artistic or parodic transformation of an image is likely a fair use, even in the presence of a watermark. At the intersection of copyright and social media, balancing the benefits of exposure with the risks of theft and appropriation is an evolving challenge.