I have been writing about looking slowly, taking the time to see the visual world. My first column was about a Mondrian painting, and it included some closeups made with a special macro lens. After that, I turned to the question of boredom (are artists ever bored by what they make?) and the strange fact that we miss even enormous, spectacular things in our visual world because we're in such a hurry to get where we're going.

Starting this month, I am going to explore the new Google Art Project site, which has some of the most detailed scans of paintings ever made. As the New York Times observed, it's a work in progress, and only a dozen paintings are uploaded in extreme detail. But it is a tremendous opportunity to look closely. This month I'll be using several images from the site; next month I will write an entire column on the amazing scan of Giovanni Bellini's Ecstasy of St. Francis in New York. That painting is scanned in even more microscopic detail than the Mondrian painting.

My question this month is: How does an artist know when a painting is finished?

This used to be a simple problem: when the artist had filled in the blanks, she was done. Over the past two hundred years it has become a very difficult question. Artists, critics, and scholars debate it endlessly. It's one of the mainstays of conversation in artists' studios. There is a lot of talk about intuition: artists say, "I just work until it feels right," or "I'm not sure if it's finished, but I am slowly getting the sense that it might be." But feelings can be elusive. Many painters mull over this problem for years on end. It's an unending source of fascination, like the religious paintings I discussed a couple of months ago, which entranced viewers for months and even years.)

Here I will map out three of the fundamental ways that paintings can be unfinished, because thinking about how something is unfinished is just a little clearer than thinking about how it's finished. I would love to hear from painters, or artists, critics, and viewers. Tell me your stories and thoughts on this subject! Like so much in art, it seems so simple, and yet it is ferociously difficult.

Here, then, are three kinds of unfinished paintings.

1. The simply abandoned.

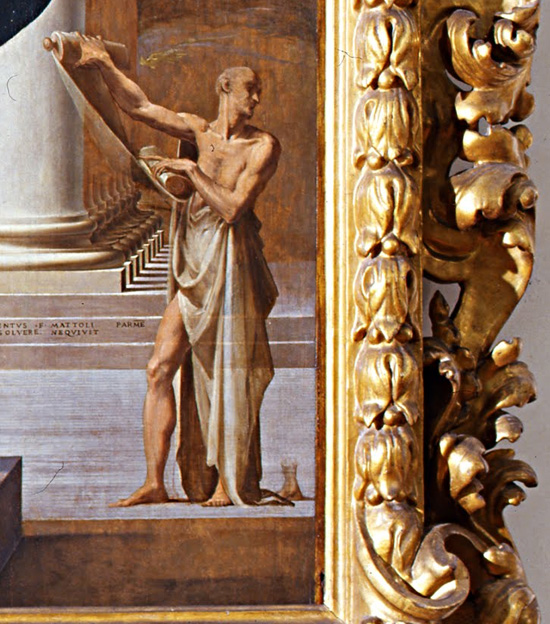

At first, this painting, by the mannerist painter Parmigianino, looks perfectly finished. This is one of the most wonderful things in the Uffizi in Florence, even if it isn't the one that attracts most tourists. The Google Art Project scan makes it look sharper and brighter than it does in the original, which makes it seem even more polished. (The Google scan is mis-labeled "Madonna of San Zaccaria," so it can be confusing to find.)

If you step up close to the painting, you notice the temple in the background has a colonnade. At the base, the columns are all painted in, but at the top, the columns and sky above the temple are unfinished.

And at the lower right, if you look even more closely, you see an extra foot to the right of Saint Jerome. It's as if Parmigianino moved him to the left, but did not completely erase the original figure, or as if there were two prophets, and then he erased one.

Parmigianino died in 1540, and it is assumed this picture was incomplete at his death. It is also possible he abandoned the painting, for one reason or another. There is a difference: if the painting is incomplete, then the artist did not intend it to look this way. If it was abandoned, he would have lost interest, and it could be interesting to know why. Giorgio Vasari, a contemporary of Parmigianino's, says the painting was left in Parmigianino's studio "perchè non se ne contentava molto" ("because he wasn't satisfied with it"). The art historian Sydney Freedberg thinks that Parmigianino had fully explored a certain style in the painting, so that it was "embalmed" or "entombed" and he didn't want to return to it. In that case, the painting would be incompiuta (incomplete, abandoned) and the missing details would have no special meaning.

(Ah, but these things get so complicated. It has also been proposed that the single column is more appropriate as a symbol of the Virgin than the full temple. That is possible, because in another painting, which Google has also scanned, Parmigianino made a lone column as sign of the Virgin. Parmigianino would have erased his pair of debating prophets to signal the truth of the doctrine of Immaculate Conception, rather than the debates about it. If this account is right, the painting would be unfinished "in reverse": to finish it, Parmigianino would have effaced the half-finished portions of the temple.)

2. The non finito.

The second kind of unfinished painting is called non finito: it means the artist deliberately stopped working before the painting was finished in order to create an effect. It is just barely possible that Parmigianino's painting is an example of the non finito, and that he left it as we see it in order to make it more expressive: that's just barely possible because the non finito itself had been invented by other Italian Renaissance artists including Donatello and Michelangelo, who left rough-carved surfaces in their works. Titian's Flaying of Marsyas, and his other late works, are other examples of Renaissance works left intentionally unpolished, rough, non finito.

But in general, the non finito is a Romantic idea; the ninteenth-century Romantics were in love with partial things, fragments, pieces, lost parts and orphaned forms. For a Romantic viewer, the tenuous, unpolished, wavering, dappled surface was far more evocative than the veneered and polished surface.

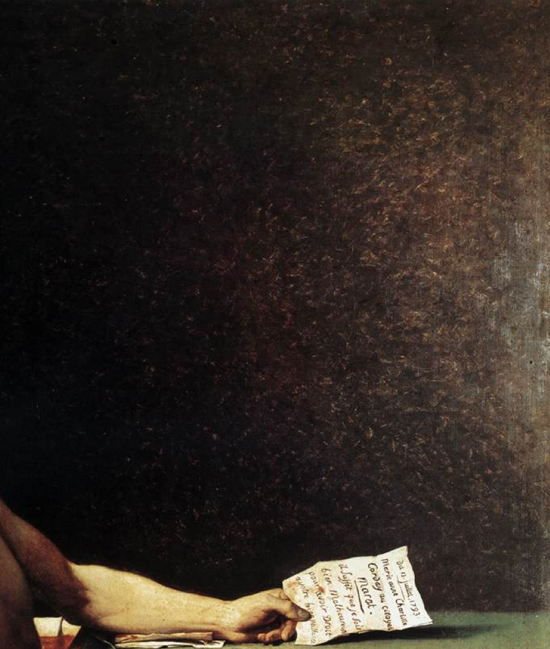

One of the first paintings that is deliberately, provocatively, non finito in this sense is Jacques-Louis David's painting of Marat, one of the martyrs of the French Revolution. (This one isn't in the Google Art Project yet.)

David, Death of Marat. Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts.

In the painting, Marat has been stabbed while he was in a mineral bath. (He was wearing a vinegar-soaked bandana, to relieve the discomfort of his skin condition.) The martyr's body is done in a spare, almost-too-thin kind of paint that David was experimenting with, but it is at least minimally finished. It's the background that is problematically unfinished. It is possible just to see it as the mottled brown underpainting that David and other eighteenth-century painters always put down when they started their paintings, and it is plausible that David's painter friends and students would have seen it that way. But for another sort of viewer -- the kind who would be more likely to commission David's paintings, for example -- that background is decidedly odd. It can be read as a symbol of Marat's unfinished life, and it fits the fact that the painting was shown, and even taken through the streets, as an emblem of the Revolution. Anyone who would have looked closely enough (although it is difficult to imagine anyone looking in quite that way when the painting was surrounded by crowds) might have understood that background as a token of the haste, the emotion, the tragedy.

All that might have made sense in the time of the French Revolution, but for the past two hundred years the painting has been in quiet rooms, and people have looked at it very attentively. Under those conditions, the patchy painting on that wall seems like a fascinating innovation for its time, something that was entirely new in 1793.

The art historian T. J. Clark has written a wonderful page on that wall in a book called Farewell to an Idea. He thinks the painting has a pivotal role in modernism, because it was the first moment when painting itself had to be reinvented, from the ground up, for its imemdiate context. The background is the obscure sign of that reinvention: it reminds us the picture is about real politics, at a particular moment, and that the painting itself would not have been true to that moment if it had been stocked with the conventional interior decorations David was so good at supplying.

The most intensely pondered examples of the non finito are Cézanne's paintings. In Parmigianino's and David's paintings, the unfinished portions can be completed in imagination: the viewer knows, from comparison with completed pictures, roughly how the finished product would look. Modern works that attempt non finito effects can be more radical, because it can be impossible to know how the gaps would have been filled. The earliest modern pictures where the imagined process of completion is uncertain are, I think, Cézanne's late landscapes. Even now, after a century of study, it remains impossible to say what the paintings of Mont St. Victoire would look like if Cézanne had continued working on them.

Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Les Lauves. Basel, Kunstmuseum.

What is "missing" from the loosely delineated passages, like the parts around the mountain?

Because paintings like this were never conclusively finished, it is possible the non finito portions are actually the more detailed ones, so that they lack a lack of detail: the exact opposite of the Madonna with the Long Neck. (Some people avoid this question by saying Cézanne's landscapes are part of a series, an ongoing experiment: but that begs the question of what, in any given image, made Cézanne satisfied, impatient, bored, or unhappy.)

Given that Cézanne was dissatisfied with some of his late works, and that they are all in some sense experiments, can we see what disappointed him, and where?

Cézanne, Still Life with Apples.

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, from the Google Art Project.

Or to return to the question of this column: if a painting like this is finished, what does "finish" mean? Older non finito pictures are finished works, but they consist of passages with conventional, predictable finish and others that simply lack that finish.

And if unfinish is not absence -- as in the Mt. St. Victoire painting -- how can we identify it? What is finished and unfinished in a cubist still life?

If it is no longer possible to distinguish the completed from the intentionally incomplete, the ideas of process and method also become unintelligible. A painting might be constructed from absence to presence, or erased from presence to absence; there is no way to be sure.

The non finito remained problematic throughout twentieth-century painting. Would De Kooning have "fixed" the "blurred" passages in his early portraits? Is the cloudy right arm of the figure in The Glazier (1940) an erasure or a sketch?

Willem De Kooning, The Glazier. New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Is the painting best read as a record of De Kooning's process, or as a completed image? And -- here's a truly difficult question -- if it is both, as I think most people assume, then what in the picture tells us so? It's a truism that De Kooning's early paintings show both the creative process and the finished work. But does anything in the paintings assure us of that?

(Everything I have been saying here has its parallels in literature. There is, for example, Kafka's novel The Trial, which is lost in its own labyrinths. If it had been definitively finished, in a way it would have been ruined, because it is all about the endlessness of the Law. A more complicated example is Roberto Bolaño's enormous novel 2666, which links to many of his other books, and is itself made of several books. Within 2666, there is an entire novel that details murders of women in Juarez, and that list, as Bolaño knew, can never be completed. But I'll stop myself here, because looking, rather than reading, is my theme.)

3. The perpetually unfinished painting.

Last, there is the painting that cannot be finished because it is infinite, because the artist is in the grip of a compulsion. In the December column I mentioned Roman Opalka, who has been painting numbers, from one toward infinity, since 1965. An older example is the compulsively detailed Fairy-Feller's Master Stroke, by the schizophrenic Victorian painter Richard Dadd.

Nominally, this painting is finished, but actually that's only because Dadd painted up to the very limit of his eyesight and his capacity to hold the brush, and then went on to the next painting. In that sense the painting is the record of an interminable compulsion, and it could never be finished.

(This is a Google Art Project image: it's too bad they don't have it in more detail, because there's lots more to see.)

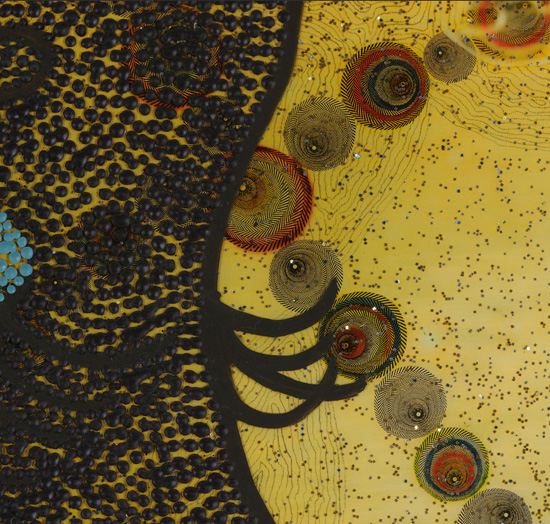

And to end with a contemporary image: is Chris Ofili's No Woman, No Cry in the Tate Britain entirely, decisively, finished?

The painting has outrageous, unbelievable detail. Here is a close-up of the woman's eyelashes. (This image is one of the featured ones on the Google Art Project, and the level of detail is nearly microscopic, far beyond what you see when you look at the actual object.)

Does it make sense to say this painting is finished? Or is it more like the record of a period of exhausting, myopic work? A painting like this asks to be seen all at once -- it's dazzling -- and it also asks for an impossible amount of viewing, from an impossibly patient viewer. A painting that can never be finished may be the sign of a patience so extreme it has become pathological.

*

Once, a picture was built. Making a picture was like building a house: you didn't begin with the roof, or call it finished when a wall was missing. Parmigianino's painted temple is under construction, like a real temple might be. In modernism the metaphor of making is no longer architecture, and in its place there are radically different concepts of how pictures are made. A non finito painting can be a sign that the painter could no longer go forward or backward. It could also be a sign that the unfinished portions seemed more expressive than the finished parts -- but then why not keep destroying those dull, completed passages and make the whole thing more expressive?

As an artist, you can become so confused that you just put down your brushes. That, too, is a form of non finito.

So now I'm not sure if this column is finished. Please post your thoughts about finished and unfinished works, and we'll see.