Just off the expressway that links the Italian stoned mansions in the Nigerian capital of Abuja's pricey "Minister's Hill" neighborhood to the settlements of corrugated tin roof shacks in the outskirts, is a nondescript path that leads to Dei Dei, one of Abuja's low-income communities.

The road is dotted with fruit sellers and their sumptuous piles of mangoes; fleets of motorcyclists honking impatiently at giggling hijab-wearing girls crossing the street; lily-white Barbie-like mannequins draped in secondhand bras and panties for sale; and stray goats, chickens and dogs.

Just off this road, on the right hand side is a field -- enclosed by a fence where guys urinate -- of cars parked over orange skins, latex condom wrappers, crumbles of leftover cigarette stubs and shards of glass from broken beer bottles.

A gray 2004 model Toyota Corolla is parked with others. The steering wheel security lock is activated. The car belongs to a 30-something year old guy named Abdulaziz Abdulaziz.

He describes this place as a "criminal's den."

"So one has to be watchful, especially with cars that can easily be stolen or broken into," he says.

Abdulaziz lives in the heart of Nigeria's capital city of Abuja, thirty minutes away from Dei Dei.

Normally, Abdulaziz would not be here, but something has lured him and that something brings him and more than a thousand others back here several times a month.

It's a cultural custom called dambe.

An age-old traditionThrongs of men sit on handmade wooden stands. Prostitutes with kohl-ringed eyes and hair covered under veils strategically meander through the swarm.

Soon, the dambe game will begin.

A boxer walks around the dandali, the ring. There's a dambe match every day in Abuja's Dei Dei community. Sunday brings the most crowds, usually around one thousand.

In the past, Hausa (one of the largest ethnic groups in West Africa and are mostly found in northern Nigeria) butchers travelled to villages to slaughter animals for various occasions like weddings and festivals. During or just after the harvest period, butchers organized fights to display their bravery and attract single ladies.

The practice has evolved to a full-fledged competitive martial art form, broadening beyond the traditional butcher caste of the Hausa people to incorporate youth in communities across Nigeria, Chad and Niger.

These days, the boxers don flamboyant hairstyles -- fades, Mohawks, twists and hair colors -- gold, red and black, mainly.

Catchy stage names complete their celebrity appeal. There's a boxer named "Horror" from Katsina State. Another is called "Ebola."

Dambe fighters get ready to enter the ring on a Sunday morning in Dei Dei, Abuja

Dambe is usually described as traditional boxing. Kicking is also permitted but is less popular in some variations. The boxers line up to enter the dandali, the ring. There's a dambe match every day in Dei Dei. Sunday brings the most crowds, usually around one thousand.

No one knows how long dambe has been around.

Sani Aleka, a dambe coach, says the game appeared in Hausa land around the 1940s.

Dr. Ibrahim Satatima, a Hausa scholar and professor at Bayero University in Kano, says the sport's history is much longer and is now an "institution."

"Dambe has been in Hausa land since before the advent of Islam," he says. "And Islam came into Hausa land between the sixth to seventh century."

Satatima adds that dambe is a source of pride for many Hausa people. It's a symbol of cultural identity that he hopes will remain.

After three rounds of kicks and jabs, the unarmed boxers are sometimes left with broken jaws, bleeding eyes, shattered teeth or cracked ribs. The punching hand -- called the spear -- is tied with a strong cotton rope, called kara, while the weaker hand acts as a shield for self-defense. The aim is to knock down or "kill" the opponent.

In the days of yore, pieces of glass were tied with the rope to produce maximum injury. That practice is now banned, but the brutality of the sport remains.

Cases of boxers dying in the ring are not unheard of.

The violence of the game stuns Abdulaziz, who just started going to Dei Dei to watch dambe a few months ago.

He winces as two slim young men, swipe at each other's faces in the middle of the ring. One guy stomps. Dust rises with the slamming of his foot on the earth. The other one bares his teeth and slaps his own thigh -- it's a popular intimidation tactic.

The barefoot, bare-chested boxers pace around the dirt ring with sweat spilling over their eyebrows. In half a second, one boxer falls flat on the ground. Everyone stands up to behold the fallen boxer's shame.

He's been "killed" as they say.

He hides his face in embarrassment as the victor parades through the crowd behind a procession of kalangu and dan karbi percussionists.

The victor poses before his fans, flexing his muscles and running back and forth to bask in his glory. He's a 23-year-old boxer known as Shagon Dan Kanawa, which means "son of Kano," a reference to the famed city in northern Nigeria where he comes from. His real name is Mohammed Izazuddin Hassan and he's been on a winning streak for several months.

He gives a speech to the crowd, thanking Allah and thanking his mother for praying for him. He kneels down before the singers as admirers come one by one to drop cash on his body.

Naira notes fall around Hassan.

For Hassan, a poor Hausa boy, this is what dambe is about -- a moment to be a hero, an opportunity to earn anywhere from $20 up to $500 for defeating an opponent, a chance to escape the reality of what can be humiliating poverty in Nigeria, especially in Abuja, the city where poor people like him feel totally unwelcome.

After winning a match, Shagon Dan Kanawa, whose real name is Mohammed Izazuddin Hassan, kneels to receive cash from his admirers

After winning a match, Hassan kneels to receive cash from his admirers

Hassan poses with his posse

The Class DivideSnuggled in the valleys of rocky hills and eroding monoliths, Abuja's sprawling landscape underwent a decades long transformation to become one of Africa's first planned cities, one of the continent's most expensive to live in and one of the world's fastest growing by population.

Local and international firms, including that of the renowned Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, designed the city's architectural elements.

Abuja, with its palatial houses and expensive restaurants, is often seen as a haven for the country's looters.

One taxi driver frowns at the mention of Abuja.

"Abuja is where the people who have stolen and chopped this country's money stay," says the taxi driver in Pidgin slang English. He asked to remain anonymous.

"Me, I no like Abuja at all. It no be for poor man like me."

For many, Abuja represents the years of kleptocratic regimes that left millions of Nigerians poorer in an independent Nigeria than they were when they were living under British colonial rule.

Abuja is a reminder of the billions of dollars in oil revenue siphoned by government officials since the 1956 discovery of crude oil in the country's oil-rich Niger Delta region.

Abuja epitomizes Nigeria's cavernous class divide where a tiny minority of multimillionaires live on one end of the cave and millions live in abject poverty on the other.

The poolside at Abuja's Transcorp Hilton hotel is a popular hangout for the wealthy. It's one of the most profitable Hilton hotels in the world and is the most expensive in the city, with rooms starting around $250 a night.

Abuja's exclusive highbrow multimillion dollar neighborhoods are tucked away on tree-lined boulevards

Abuja's sprawling landscape underwent a decades long transformation to become one of Africa's first planned cities, one of the continent's most expensive to live in and one of the world's fastest growing by population.

A red-carpet affair at a rooftop lounge in Abuja

With a population of at least two million, Abuja exists in its own parallel reality mounted firmly on a culture of elitism. Here, a bottle of water at a hotel can cost $5. A full course meal at a restaurant in an upscale neighborhood may start at $40. Rent for a decent one-bedroom apartment in the city averages around $13,000 a year and that yearly rent is expected upfront. A pair of mediocre quality men's leather loafers at the mall can cost at least $125. The hefty importation levies, the volatile forex market, cost of electricity generation, rent and bribe money account for the exorbitant cost of goods.

Business tycoons and their foreign partners go out to play at the golf country club named after Ibrahim Babangida, the former military ruler who is often credited for institutionalizing corruption in Nigeria.

Children of the elite, driving in the latest models of SUVs on the false ashoka tree-lined boulevards, go club-hopping, spending lavish amounts of money on endless flows of Dom Pérignon. With their British or American accented English, they order plates of local delicacies and continental staples.

Red-carpeted birthday parties and weddings at choice venues bring together the who's who of Nigeria's elite: the old money families of politically powerful retired military generals, politicians, oil and gas moguls, Nollywood celebrities, the nouveau riche oligarchs with real estate properties in Beverly Hills California, London's platinum triangle or Dubai.

But beneath the glitz and marble terraces, discreetly tucked in the shade of acacias behind the sidewalks are children wearing holey flip-flops and women crouched on the ground holding their babies.

When cars stop at the traffic light, they all rush forward to plead for money.

More often than not, they're left empty-handed, standing in the red glow of taillights.

Dodging between cars, boys and girls selling everything and anything from groundnuts to wiper blades sprint at the sight of the city's task force officers.

Street hawking is not allowed. If the boys and girls are caught, the officers could seize their wares.

The message is clear: Abuja is for the rich.

A woman walks around to beg at an open air market in Nigeria's capital of Abuja

A beggar sits with his money bowl along a road in Abuja

Working class women walk past an residential building under construction in Abuja. Rent for a decent one-bedroom apartment in the city averages around $13,000 a year

Dei Dei is one of the larger makeshift settlements in the outskirts of Nigeria's capital city of Abuja. Here, the government's supply of electricity and water is almost nil. Sanitation is low. Petty criminality is high.

Between the ongoing evictions of the indigenous Gwari people who inhabited Abuja for centuries and were forced to leave their homes to make way for bulldozers and then the demolition campaign of Nasir El-Rufai the former minister who governed the city from 2003 to 2007, thousands of working class people have been displaced over the years in Abuja.

Local journalists branded El-Rufai's initiatives as a war against the poor.

Some displaced people are squatting in empty over-priced residential properties and abandoned construction sites across the city.

Most of the people who work in Abuja's city centre cannot afford to live there. They live in the shanties clustered along the thoroughfares.

Driving home after a dambe match, Abdulaziz sees the lines of cars and public buses stuck in traffic, headed to the outskirts.

"It's really cruel, this class thing," he says. "The city is highly segregated between the rich and the poor and the poor get very shoddy treatment because actually the slums, because I wouldn't call them settlements, the slums around Abuja are just not habitable. You see places with no access road, no water. Some places don't even have light. And the arrangement is just haphazard and to access some places is hell. So, to think these are the people servicing the city, but being dismissed into some places is just not right."

Dei Dei is one of the larger makeshift settlements.

Here, the government's supply of electricity and water is almost nil.

Sanitation is low.

Petty criminality is high.

Yet, every Sunday, hundreds of people go to Dei Dei to watch dambe.

"A Poor Man's Sport"The grittiness of dambe contradicts the ostentatious wealth of Abuja.

At the Dei Dei dambe boxing ground, Abuja's laborers come out to cheer on their local champions while politicians and government contractors throw dice at the casino in Transcorp Hilton Hotel in the swanky Maitama district in the city center.

At the Dei Dei dambe boxing ground, a toenail cutter walks around with his rusty nail clippers, making hissing sounds to call for customers. In Abuja's city center, clients in LED -lit spas rest their feet in the hands of pampering pedicurists.

The dambe spectators buy ice cream from a guy spooning it out from a dirty cooler that he wheels around, selling at 100 naira ($0.50) a cone. Hip, 20-something-year-olds pay six times that amount for a small cup of ice cream at a parlor in the city center.

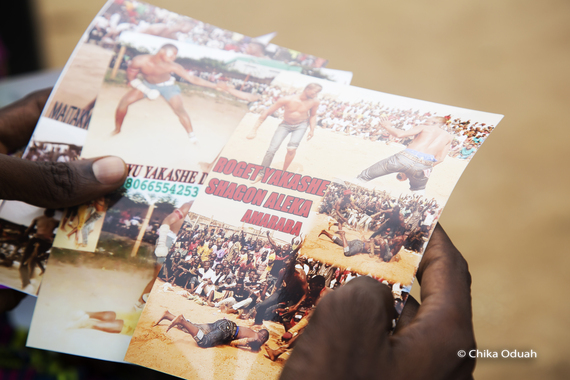

Dambe spectators go through printed photos of dambe boxers to decide which ones to purchase. The pictures go for 100 Naira ($0.50) each.

At the Dei Dei boxing ground, marijuana-joint-puffing men in caftans or denim jeans walk by to sit in the area in the stands that's designated for them. Their wrinkled, pockmarked faces bear the hardness of a life of hustling.

"This is a poor man's sport," says Jafaar Jafaar, a friend who accompanies Abdulaziz on a Sunday morning where almost one thousand people have showed up. Abdulaziz and Jafaar -- young, trendy middle class guys living in the city center -- are a bit of an oddity in this crowd. They're cultural aficionados. Abdulaziz says his friends jeer at him whenever he tells them he going to Dei Dei to watch dambe.

Not only are most of the dambe spectators poor, the financially unstable boxers are also teetering on the poverty line. One day, they're OK and the next, they may be out of cash for weeks.

So, they play with passion.

Each strike could determine if a boxer can afford to pay next week's rent or not.

The drumming excites the awaiting boxers. The singer's voice rises.

"If it is your turn today, tomorrow it will be someone else's turn," he sings in Hausa.

The fighters are decorated in amulets -- strands of animal hairs wrapped around gemstones, verses of the Koran written on scraps of paper, other mystical things stuffed into leather pouches.

A boxer wears a leather pouch of charms around his neck. The fighters are usually decorated in amulets- strands of animal hairs wrapped around gemstones, verses of the Koran written on scraps of paper, other mystical things stuffed into leather pouches.

The boxer, Shagon Dan Kanawa, whose real name is Mohammed Izazuddin Hassan, bends down to draw figures on the dirt. This is a spiritual fortication ritual

Though most of the boxers say they are Muslims, syncretistic spirituality is deeply entrenched in dambe. Spiritual guides nurture the boxers. Each boxer undergoes an elaborate fortification ritual. They wear charms tied around the neck. They drink homemade herbal tonics. They mix leaves with their blood.

Their arms are lined with dozens of self-inflicted scars.

The shiny mounds of healed flesh give Hassan's arms a reptilian look. He said some of the scars are just a few weeks old, made with a small blade. First, he cuts. Then, he pushes grounded leaves inside the bleeding gash.

Also, the palm of his punching hand is painted red and black with herbs and lalle, henna.

"When I don't use this, I won't have power in the hand," he says.

23-year-old boxer known as Shagon Dan Kanawa, whose real name is Mohammed Izazuddin Hassan, wears henna and an herbal mixture on his punching hand as part of a spiritual fortification ritual

The arms of dambe boxers are lined with self-inflicted scars. Hassan used a a small blade to make tiny cuts in his arms. First, he cuts. Then, he pushes grounded leaves inside the bleeding gash as part of a spiritul fortification ritural.

A few weeks ago, he was punched in the chest by a boxer who he says used spiritual power.

"Him use poison to blow me in my chest," he says. "You know the blow that is not normal."

Like other boxers who experience injuries, Hassan did not go to a hospital to treat his chest wound.

"This na traditional boxing and na traditional medicine you will use to drink," he says.

A spiritual healer gave him a potion to drink. After he drank it, Hassan says he vomited green liquid. He believes the liquid represented the supernatural poison leaving his body. After vomiting the green stuff, Hassan says he regained his power and returned to the ring, winning one match after the next.

The spiritual element elevates dambe from a game that is far more than sport. This is Hausa culture.

"It's the only traditional thing that I can spend time on," says Lawal Mohamed. "I come here several times a week. If I am not here, my mind will not be at rest. I will be thinking about dambe."

The 51-year-old used car salesman started watching dambe when he was 9 years old.

Today, he was so eager to go to Dei Dei that he told a customer who was about to pay for one of his cars to wait until after the game.

It's these sorts of fans keeping dambe alive, but many of them would never allow their children to play.

Deep down, they know that even though dambe boxers are celebrated in their local communities, the glamour of it all is fleeting. Dambe boxers live the rough life.

With each painful blow, dambe fighters sacrifice their bodies to preserve a cherished Hausa tradition.

After three hours of dambe, the crowd disperses. The tiger nut sellers disappear. The photographers selling printed photos of dambe champions walk away. The ice cream cart is gone. The popcorn is finished. Flies wrestle other flies for discarded morsels of sugarcane. Sex workers stroll out alongside their customers. The musicians pack up the drums. The boxers hop on motorcycles or duck into vans to return home.

The ring is left barren with Abuja's silent mountains wrapped around it.

Dambe's Uncertain FutureHassan and some of the other boxers live in the red-light community of Tafa. It's a noisy truckers' stop along the expressway from Abuja. Drug dealers sell their illegal goods without hiding. Recent police raids in the area uncovered local gang leaders.

Abdulaziz describes it as a place for "people of the underworld."

"See the girls?" he asks.

One guy sits alone, intoxicated.

The son of a housewife and an Islamic scholar, Hassan feels different from the other dambe fighters. He does not smoke and condemns the other boxers for their drug addictions.

"Some boxers are not going to school and they can't speak English or Arabic. They no know Allah. Me, I want to go back to school. I finished secondary school. I speak Arabic," he says.

He wants to study electrical engineering at a university.

With the money earned from dambe, Hassan bought five cows. At the market, each cow can fetch at least $500. He gives money to his widowed mother and his six siblings. He pays university fees for one of his brothers.

Hassan knows that his days as a boxing hero are numbered. He knows that the constant battering on his body could destroy him or leave him penniless, the same way it has left former champions fading away in villages, miles away from dambe's crude spotlight.

52-year-old former dambe champion, Abdulkadir Lawan played for eight years.

With a dislocated thumb, yellowy eyes and deep etches of wrinkles on his body, Lawan says he regrets ever playing.

"I don't even want my eight children to do dambe," he says.

Lawan, a jolly and spirited fellow, wears the charms worn by other retired boxers to symbolize the spirit of dambe. He is an important figure in dambe and shows up to the Dei Dei boxing ring everyday to entertain the crowd with his dancing and jokes.

52-year-old former dambe champion, Abdulkadir Lawan played for eight years. He is an important figure in dambe and shows up to the Dei Dei boxing ring everyday to entertain the crowd with his dancing and jokes. Here, he his is bundled in an exaggerated "spear" for comedy

But he's planning to retire from that role as well.

Dambe faces an uncertain future in Abuja. Pressure from the government has forced the dambe organizers to relocate at least five times in the past ten years, according to Aleka.

However, the owner of the Dei Dei boxing ring, Ali Zuma, is optimistic about dambe's future. Men from other ethnic groups in Nigeria, like Igbo and Yoruba, are also starting to play dambe. Zuma says this cultural assimilation can help preserve the sport. Zuma tries to get wealthy men to patronize the sport.

But Zuma is also accused of being part of the problem. Boxers complain about his management.

Many say that he does not pay them well. Hassan's chest injury from a few weeks ago left him out of the ring for five days. He says Zuma did not compensate him, though he felt he should have.

Hassan thinks about money a lot. He wants more of it so that he can move from where he lives. It's a dark one room with a cement floor. His accommodation is so embarrassing to him, that he doesn't even want his siblings to visit him.

Hassan stands in front of the room that he rents in the outskirts of Abuja

On this Monday morning, Hassan walks over to his room and finds the door locked.

The landlord just locked him out.

It's the third time this year that he has been locked out of his room for failure to pay his rent. It's 2,000 naira ($10) a week. He'll have to sleep in a friend's place tonight.

But Hassan doesn't look fazed. It's the life of a dambe star.

"You see, this old room is my room," he says. "And because of only two thousand naira they done close the door."