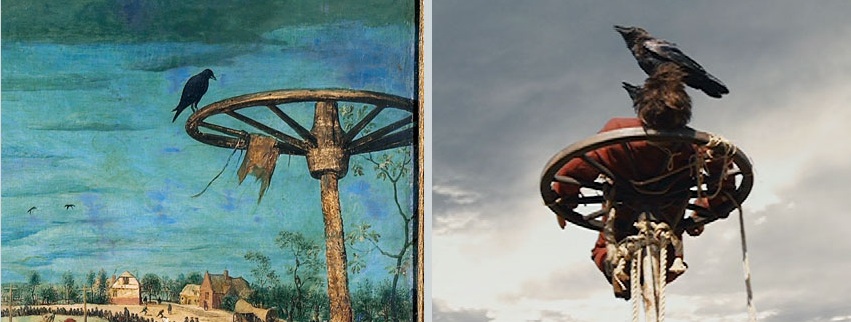

Film still from The Mill and the Cross, 2011 Directed by Lech Majewski - Credit: Kino Lorber, Inc.

Some time ago as part of my long fascination with Venetian culture, I came across Lech Majewski's impassioned film, The Garden of Earthly Delights, a doomed love story told through meditative and erotic enactments of Bosch's painting, a contemporary vision of Visconti's Death in Venice, shot in that fabled floating city, which the Polish filmmaker now calls home.

Charlotte Rampling - Film still from The Mill and the Cross, 2011 Directed by Lech Majewski - Credit: Kino Lorber, Inc.

An accomplished artist and composer, Majewski, also wrote and co-produced Basquiat, directed later by his friend Julian Schnabel. His new feature film, The Mill and the Cross with Rutger Hauer, Michael York, and Charlotte Rampling playing Mary, is an elaborately layered, computer-generated tableaux of another classic, Pieter Bruegel's 1564, The Way to Calvary - a composite of multiple light sources and seven different perspectives that Breugel had used to trick the eye.

In the painting, Jesus's crucifixion becomes marginalized by a vista of colourful onlookers, bread-sellers, squabbling hawkers, inquisitors and their victims strapped to Catherine-wheels, all strewn across the landscape. A windmill perched on a high crag casts an all-seeing messianic gaze over the landscape, its lazy blades turning the cogs of time.

The Way to Calvary, Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Kunsthistorisches Museum Burgring, Vienna

During our conversation Majewski and I chatted about animal suicides, latent cruelty, and the art of animating paintings.

Do you think Bruegel had a cynical view of humanity, suggesting that we are numb to others' sufferings as a way to ensure our own survival?

Not at all, he is a realist in looking at human conditions. He is a profound observer. I feel a lot of compassion in his paintings, a softening for Flanders and its people. He is compassionate in his depiction, but realistic...it is the inbred condition of human beings, that's the way it is...to be cynical you have to be on purpose, so to say.

Does this translate to a modern day view of humanity for you?

His message is timeless, anything important happens, you most likely won't see it because you just don't see beyond your own nose...the foreground is less important...Bruegel's attitude is truthful, I mean people go after the incidents that catch their eyes, but that's not necessarily the most important thing happening around them.

People have to be particularly stronger today as we are attacked by many aggressive disruptions, whether we like it or not. Disruptions to our train of thought are constant; if you want to communicate with yourself there will be constant interference - radio, TV etc.

It's a way of avoiding being alone. The film dwells on the cruelty - the Catherine-wheels with crows pecking at the mangled remains of victims - was that method of execution common practice at the time? I think of Prometheus, and also the Zoroastrian practice of exposing the deceased to birds of prey.

That's right, you shouldn't steal the fire from the gods. Bruegel is a profound philosopher. His paintings are like Fellini movies, full of heart; painting live people, caught in their originality. So many tortures invented at the time - Spaniards were very cruel; are cruel by definition, so to speak; it wasn't by chance the Inquisition happened in Spain; the conquering of South America was an exercise in cruelty. The same cruelty was applied to Flanders, and countries they were conquering.

A heretic executed' - Detail from painting and film still from The Mill and the Cross, 2011 Directed by Lech Majewski - Courtesy of Kino Lorber, Inc.

Film still from The Mill and the Cross, 2011 Directed by Lech Majewski - Credit: Kino Lorber, Inc.

Rutger Hauer, Film still from The Mill and the Cross, 2011 Directed by Lech Majewski - Credit: Kino Lorber, Inc.

Your films have a pensive mood to them; what do you think?

But I can't comment because that's your take. I have no idea; [laughs] things come from me and I don't control them - I am also trying to be truthful to my experience of life. Life is not the easiest to live, especially when you start to think, and observe, see what humans do to humans. What they did in history and what they are doing today. We are living in a painful world - the majority of this pain inflicted by ourselves.

Perhaps it's our ability to choose that makes us crueler? We can murder, but animals usually kill for food. You could say suffering is exacerbated by our own awareness. We glimpse transcendence though often fall short of it; knowing our own frailty causes more angst.

Nature provides events that are somewhat foreseeable, like earthquakes, volcanoes, mudslides, because they are limited to certain areas...in ancient societies people could foresee those things; if old enough they could remember past events through oral traditions; people were prepared to deal with it.

In the animal world there is also a certain amount of predictability in who will be subject to attack and who will defend. Survival of the species - those who are attacked develop a system of defences - speed, a sense of smell or hearing. I would call it fair game. There is logic to behavior.

Once humans enter, logic is suspended and subject to abstract manipulation - which can produce idiotic schemes for destroying other humans.

Fortunately animals are devoid of ideas on how to exterminate a group of people, or themselves for ideological reasons. It's a matter of survival - but it doesn't go beyond that.

Not having abstract thoughts would exclude the possibility of a belief in god - the kind of complexities humans deal with.

We are animals, but we cannot know what other animals think. I would argue with you that certain dogs develop a very strong godlike feeling towards their masters - they could starve to death for them.

But animal suicides are rare - they would have to override their instinct for survival right?

We cannot know...but definitely some of them seem like they have higher thought. Survival of the species is well developed among them - and what about dolphins, dogs and chimpanzees. It is off-limits to us, a subject of speculation.

I've heard that if you put the same number of chimpanzees, as there are humans on the island of Manhattan, there'd be a huge massacre - they cannot live in such close proximity as humans do - so we must have some level of compassion toward others, living as closely as we do.

Whenever you talk about human compassion - another question that crops up is what about Auschwitz?

Film still from The Mill and the Cross, 2011 Directed by Lech Majewski - Credit: Kino Lorber, Inc.

What about your own religious upbringing? It plays an important role in your films.

Obviously in Poland 99% people are catholic, even more than in Italy, comparable to Ireland really. For perspective, most historical occidental art is somewhat a dialogue with Christianity - if you look at the major paintings, musicals, poems, books and major symphonies, you cannot remove the religious factor in them.

Modern times are devoid of this. Being more atheistic leads nowhere. In my opinion you have to have a relationship to religion.

In my personal life I got a wake-up call from a Hindu person: Rabindranath Tagore. He woke me up to an inner life when I was sixteen. He was the most important spiritual father to my life, my creations, his aphorisms; his poetry is beautiful.

The mother figure often portrayed in your film is virginal, creative but unable to express her creativity, unhappy, and somewhat magical, seen through the eyes of a child - is that autobiographical?

Yes, good reading.

And then you picked Charlotte Rampling to play the Virgin?

Against the grain; it made sense to me; She also chose the role.

Charlotte Rampling - Film still from The Mill and the Cross, 2011 Directed by Lech Majewski - Credit: Kino Lorber, Inc.

Garden of Earthly Delights reminds me of Basquiat - the urgency of celebrating one's life as it comes to an end. After writing Basquiat, why did you choose Julian Schnabel to direct it?

Jean-Michel Basquiat's father was very much opposed to that script because he was the villain of the film, and threw a lot of obstacles. Ultimately I left the project to Julian and he sanitized the scenes with the father. We didn't get permission to use Jean-Michel's paintings, so Julian had to create the artwork and put in his effort and money. It was my brainchild, but after 2-3 years of knocking on everybody's doors, I left the project with Julian, and he single-handedly delivered it by putting in his own resources. So, it came about thanks to his stamina.

What about Greenaway's Last supper? Or Eve Sussman's Las Meninas?

[Greenaway] is not my kettle of fish. He is technical; it's just soulless calligraphy - but I'm not criticizing a fellow-filmmaker. It is theatrical but empty; he doesn't go beyond, like Tarkovsky does...

Animating a painting involves all these extra dimensions - a past, present and future - a front and back, and a movement through time.

Yes four dimensions...it was like weaving a tapestry and unbelievably complex to make it. [The composite] had a minimum of 40 layers and a maximum of 147, so every shot was layered.

The windmill as an ancient method of manufacturing energy is incredible. I realize now that it is a grain-making mill, mechanized by wind.

The windmill was constructed from parts, and shot in the Czech republic. I painted a tree of Breugel's, and cities and clouds to extend the landscape, which was cut in half. I animated branch by branch, so the leaves can move in the wind. The sky I shot in New Zealand. [note: the Maoris named the South island 'long clouds' for they run like rivulets and streams, and are almost a 'show to watch']

So you completed Bruegel's painting...

My respect for him is even greater now...

For more information on film: http://www.kinolorber.com/themillandthecross/

Text & Interviews: www.KišaLala.com

Kiša Lala on Facebook