This coming Saturday, the population of South Asia will celebrate a holiday that hasn't yet caught on in the West.

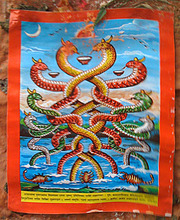

Nag Panchami is devoted to the worship of snakes: nagas in most Asian languages. Throughout Nepal and India, families will prepare ceremonial offerings of milk, and tack colorful posters of knotted serpents above their doorways. The ancient rite honors the role of snakes in both mythology and daily life--asking the reptiles to bring nourishing rains, and spare devotees from snakebite.

Nepal's bond with nagas began in pre-history, when (as sages and geologists agree) the Kathmandu Valley was a vast lake, populated by a race of powerful snake gods. These nagas and naginis lived in watery palaces, festooned with gems. They served as wardens of the seasonal rains, and guarded the Earth's underground treasures.

Eventually, a Buddhist saint named Manjushri hiked the ridges surrounding Kathmandu. He sliced a gorge in the foothills, draining the lake so that humans might settle. The irate nagas fled, relocating in aquifers, rivers, and nag pokhari: smaller "snake lakes" that punctuate the now congested Kathmandu valley. Though subdued, the nagas still command awe and devotion. Their resident ponds are shrines, where people planning a new house (or other earth-shaking enterprise) pour milky offerings into the water.

For western visitors, this close relationship with snakes can be disconcerting. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, snakes are seen as evil and cunning: agent provocateurs that seek to corrupt our souls. Examining the Western prejudice, it's clear how superficial (and misogynistic) it is. Our loathing seems to date back to a single morning in Eden, when a famous episode of serpentine generosity was falsely cast as a duplicitous dare.

"Ignorance," an antediluvian naga cautioned Eve, "may be bliss--but it's also ignorance. But don't take my word; have a bite of this fruit."

At which point Eve--whose courage would be twisted into a betrayal of everything holy--helped herself.

Was the snake wrong? The snake was right. Yet despite that defiant serpent's sacrifice, something inside of us that clings to dependency, and the lost innocence of the cradle, remains bitter. A snake got us chucked from our little garden, and we've been bashing them with shovels ever since.

Biologically, there may be good reasons for our innate aversion to snakes. Recent studies suggest that some aspects of human evolution--from our acute eyesight to the physiology of courage--may be rooted in the tense relationship between Cretaceous-period primates and these reptiles.

Maybe that's why we've rewarded them with such a high profile in our collective unconscious. Charismatic snakes were appearing in western mythology more than 4,000 years ago - long before the Old Testament. One such character was Ningishzida, the Mesopotamian god of the underworld. It was this serpent that later appeared around the staff of Hermes, and ultimately slithered into modern iconography--entwined around the medical caduceus.

But snake symbolism gets much stranger. In the Kabbalah, the mystical tradition of Jewish wisdom, each Hebrew letter is assigned a number. Every word thus has a numerical value--and a powerful relationship with words of identical values. According to this ancient system of ciphers (called gematria), the meaning of the Hebrew word for "serpent" matches that of another word: "messiah."

It makes sense, when you think about it. Both snakes and messiahs are, after all, masters at the art of liberation. A snake literally sheds its skin, emerging as a rejuvenated being. A messiah offers the same opportunity, though metaphorically: a chance to re-invent ourselves, and emerge with an overhauled soul.

When Nepalis make their offerings this Saturday, they'll be thinking less about molting than about primal power. For them, the ultimate nag is the hooded cobra: the Schwarzenegger of the serpent world, found everywhere in Hindu and Buddhist myth. Lord Vishnu, the Great Preserver of the Hindu trinity, dozes on the infinite coils of Ananta, a cobra-cum-couch, for eight months of the year (during the other four, he extricates humanity from its many perils). And it was a similar snake--a seven-headed cobra--that sheltered the Buddha from the rain and sun during his seven weeks of meditation before attaining enlightenment.

My suggestion is that all of us, wherever we may be, take a moment to celebrate Nag Panchami this Saturday. Just step outside, pour a tablespoon of milk into a likely snake abode (a sewer doesn't count), and offer a respectful nod to these strange, cold-blooded creatures that have helped shape human evolution, culture and spirituality. We may never learn to love them -- but it's a probably a good idea to have them on our side.

Jeff Greenwald's new book, Snake Lake, will be released this Fall by Counterpoint

* * *