This summer, two elementary students from the same school were murdered in the same week in my hometown of Flint, Michigan. Trashawn Macklin and Cherish Hill-Renfro were only two of seven homicide victims in six days.

Trashawn, 9, his uncle Akeem Easterling, 26 and James Allen Jr., 22, were found July 15 at Park West Apartments. A troubled 18-year-old with a history of home robberies is charged with their shootings, plus one more. There was a warrant out for his arrest because he had left the drug treatment program he had been sentenced to attend.

Five days later, Cherish, 12, and her mother, 42-year-old Yolanda Hill, were found dead of strangulation and asphyxiation at Atherton East Apartments, near where I grew up on Brentwood Drive. The mother's 44-year-old ex-boyfriend has been arrested. He served 15 years in prison on car theft and drug convictions and was released in 2011.

With an unemployment rate of 16 percent, Flint consistently makes the top of the list of most dangerous cities in America. In 2012, 2,700 violent crimes (including 66 murders) were committed in this town of 100,000 people. Yet, I can attest that Flint used to be a great place to grow up. I attended Flint Southwestern Academy, where Cherish would have gone this fall had she not been murdered. Flint was a city that had it all, and then lost it.

Today, my hometown is practically a war zone, rife with gang violence, drug addiction, human trafficking and a sick economy. For Flint's children, this situation is a catastrophe.

The response to these tragedies from Flint police officials and politicians has been a predictable call for more state and federal funds for their local war on drugs.

I propose a far different two-prong solution to save Flint and other beleaguered American cities:

1) Decriminalize possession and use of small quantities of narcotics, reducing or eliminating the current lengthy mandatory sentences for non-violent drug crimes. At the same time, medical treatment for those addicted to drugs should be privately funded.

2) Provide mandatory entrepreneurship education, life skills and business literacy courses for every American child.

Flint's problems are complex, but stem in part from rising gas prices during the 1970s OPEC oil embargo, which caused many Americans to rethink "big car" purchases from Ford, Chrysler and Flint's largest employer -- General Motors.

Flint's economy was hugely dependent on General Motors, which by 1978 employed 80,000 citizens in its plants. As documented in Michael Moore's 1989 film, Roger & Me, when General Motors CEO Roger Smith closed plants in Flint and relocated them to Mexico, the impact on Flint was devastating. By 2010, only 8,000 Flint residents still had jobs at General Motors.

I have no problem with a CEO doing what he thinks is in the best interest of his shareholders -- although history has not been kind to Smith, whose tenure at GM is widely viewed as a failure. But Flint has yet to recover from its addiction to a corporate giant. The city's violent crime rate skyrocketed after GM left, as entrepreneurial drug-dealing gangs filled the unemployment gap.

Unfortunately for the young men who flooded the streets of Flint dealing crack instead of working factory jobs, and for crack users, President Reagan signed War on Drugs legislation in the '80s that set the penalties for possession of crack cocaine 100 times higher than for possession of powder cocaine, including a minimum mandatory five-year sentence for crack possession.

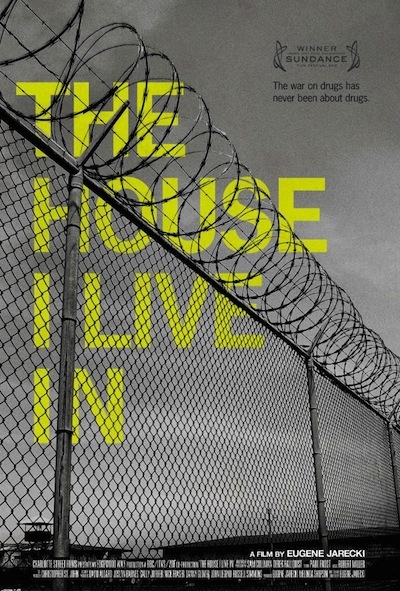

As the powerful documentary film The House I Live In -- which won the Sundance 2012 Grand Jury Prize -- illustrates, this why today our prisons are jammed with non-violent offenders serving lengthy sentences. The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world, and the War on Drugs is why. In 2008, young black men (18-34) were at least six times more likely to be incarcerated than young white men, according to a study by University of Washington sociologist Becky Pettit.

In August 2010, President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which eliminated the five-year mandatory-minimum prison sentence for possession of crack cocaine and reduced the Reagan-era powder-to-crack weight ratio for sentencing from 100-to-1 to 18-to-1. This is a step in the right direction, but decriminalization and drug treatment could do more to save our cities.

The world has its first decriminalization test case -- and the results, according to Business Insider, are "staggering." In 1999, Portugal decriminalized possession of small quantities of drugs, replacing imprisonment with treatment. Drugs like heroin, marijuana and cocaine are still illegal in Portugal, but small quantity infractions are settled in a special court where legal experts, psychologists and social workers evaluate each defendant and recommend treatment or other action. Drug manufacturers and dealers are still pursued and prosecuted, but possessing small quantities is treated as a health issue.

In 2012, The Economist opined that "Drug decriminalization has been a success everywhere it has been implemented," and urged President Obama to seriously considered it for the United States.

"Unfortunately," The Economist warned, "America's massive investments over the past 40 years in building up the machinery of the war on drugs have created powerful constituencies that have so far been effective in sabotaging moves in this direction."

Meanwhile, our smart, savvy urban youth know it's tough to get a job, and know they can make real money selling drugs -- and most of them have never been taught anything about legal entrepreneurship. If the only person in your young life able and willing to teach you how to set up a lucrative small business is a drug dealer, you would probably listen to him, too.

As a youth entrepreneurship educator for 32 years, specializing in the craft of bringing entrepreneurship education to at-risk youth in the inner cities, I've personally witnessed many urban youth choose a legal business career over the drug trade once they became financially literate. I've seen them, with a little help, start and run successful businesses, putting themselves through college and find a wide variety of pathways out of poverty. I've seen them improve their communities, and lift up others. This is why Thomas Friedman recommended in The New York Times that President Obama " should also vow to bring NFTE, to every low-income neighborhood in America."

Here's the truth about the War on Drugs -- it is because drug deals are illegal that relatively typical normal business disagreements over quantity, quality or price are often settled by violence. It is because drugs are illegal that the profit margins for dealing them are so high, and drug kingpins are able to employ our urban youth on every street corner of a desperate town like Flint.

Decriminalizing drugs and regulating their use through doctors and licensed pharmacies could eliminate much of the violence that arises over drug deals gone wrong and turf wars. Decriminalization could largely eliminate the highly profitable underground market in drugs, and reduce not only murders and assaults but also non-violent crime, such as robberies committed by desperate drug users.

If my proposal sounds radical, consider this question: Have the benefits of the drug war -- which has cost the U.S. government over a trillion dollars since President Nixon initiated it -- outweighed its costs?

- The War on Drugs has cost1 trillion since Nixon began it in 1971, yet the rate of drug use has stayed the same

- Half a million people are behind bars in the U.S. for nonviolent drug crimes

- 1.7 million American children have a parent in prison.

- African Americans are statistically ten times more likely than whites to serve time for a non-violent drug offense, and comprise 56 percent of those in prison for drug crimes.

Like The Economist, Jarecki argues that the War on Drugs is really about fat government contracts and who gets them. For the prison-industrial complex, he notes, the War on Drugs has been a huge success. For police departments who use it to get more funding and politicians who tout it to get elected, the War on Drugs has been a huge success.

Today, Jarecki told Observer editor John Mulholland in a video interview, "the tail is wagging the dog. You see this across American industries that have disproportionate and unwarranted control over the areas of policy that affect them, and so the prison industrial system in America ends up in many ways writing the laws that fill its beds."

Jarecki, whose parents are Holocaust survivors, also draws similarities in his film between the tactics used by the Nazis to marginalize and imprison Jews and other scapegoat groups, and the War on Drugs. His film illuminates America's history of outlawing drugs used by specific minority groups who are starting to succeed, beginning with opium and Chinese rail workers in San Francisco in 1875, and using those laws to imprison and disenfranchise them. Jarecki makes a convincing case that one of the primary obstacles to African American progress since the Civil Rights movement has been the War on Drugs.

Today, the War on Drugs is also hitting poor whites, with draconian mandatory sentencing laws enacted in response to epidemic methamphetamine use and sales in the Midwest. The House I Live In profiles Kevin Ott, a white man serving life without parole for possession of three ounces of crystal meth. He started dealing meth after he was laid off from his job.

Thirty years into the drug war, over 7 million people have been arrested, are on parole or are in prison. Many have been permanently disenfranchised as a result of non-violent drug convictions -- unable to get decent jobs, vote or travel overseas. Meanwhile, 700,000 prison guards and counselors make their living off the institutions that imprison these men and women.

Let's end the failed, costly War on Drugs by decriminalizing possession of small quantities and treating drug addiction like the health issue it really is. Let's beat the dealers at their own game by bringing entrepreneurship education into our schools and making our young people business literate, so they see other options. Let's bring our local business leaders into the schools to network with our youth and inspire them to look beyond the dollars they could earn on the street corner. Let's give all our youth the knowledge they need to participate in our economy, and in the process help save their lives.