There are communities in the U.S., like Dallas, which claim a large number of street dogs. To date, the proposals on what to do about it have all been lethal, including the shocking and cruel suggestion by one city council person to employ helicopter gunships to shoot and kill the dogs. Of course, shelter reform would go a long way to alleviate the issue since it would result in dramatically enhanced shelter services, better able to meet the wide ranging need of the homeless animals in a community. Indeed, implementing the No Kill Equation--a series of programs and and services which have already transformed shelters nationwide--would allow communities like Dallas to move beyond the crisis mode of impound and killing by building a sustainable, lifesaving infrastructure which is not only more humane, but which would increase efficiencies, effectiveness, community support and thus capacity to take in and save street dogs, too. But that is a process that some bureaucrats, including those in places like Dallas, seem loathe to consider, preferring to hide behind tired clichés about pet overpopulation, the irresponsible public, and lack of animal adoptability.

So while the Dallas pound continues to fail under a leadership that lacks vision and accountability and as city officials continue to excuse incompetence and promote outright cruelty to animals, what they seek is not systemic reform of root problems, but a quick and dirty fix. Wrapping themselves in the mantle of public safety, they are calling for the round up and killing of Dallas's neediest dogs.

Short of comprehensive shelter reform, what should the humane movement be promoting instead? What solution would not only begin to immediately address the homeless dog population, but would do so in a humane, life affirming manner? Looking to other nations for guidance, places where free roaming dogs are a far more common occurrence than in the United States but where humane approaches are being demanded by their dog living citizens, there is an answer: sterilizing and releasing community dogs, as is now done across the United States for community cats.

To some, the notion of sterilizing and releasing dogs is viewed as extreme. The reasons given are, ironically, similar to the arguments that used to be made for cats before such claims were debunked as sterilizing and releasing community cats gained widespread acceptance within the humane movement and government municipalities, including many health departments. They include the claims that the streets are not safe for the dogs, the public is not safe from the dogs, citizens will not accept the idea of re-releasing dogs, and it is illegal to do so. We know these arguments do not stand up to scrutiny for cats, but do they hold up for dogs? In other words, is sterilization and release for dogs a good idea in the United States?

It is. In fact, some of the early founders of our movement not only advocated against round up and kill campaigns for community dogs, they advocated leaving them alone. Others, such as early San Francisco humane pioneers, even raised the money to bail dogs out of the pound in order to release them back on the street.

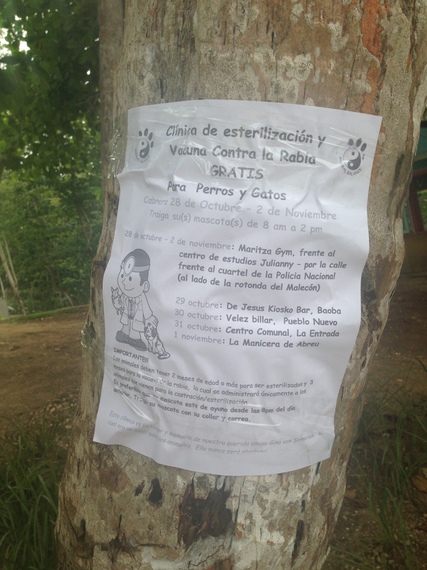

But one need not go back to the 19th century for evidence that the idea isn't so far fetched; sterilization and release of dogs, in lieu of killing, is done in other countries and even U.S. territories today. In fact, it is successfully being done in American Samoa, Independent Samoa, the Bahamas, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Cabo Verde Africa, Saipan, and the Galapagos Islands. And the reports have been universally positive for the dogs and for the public.

Dog Safety

There is, for example, a large community dog population on Playa Grande Beach on the North Coast of the Dominican Republic, but no animal shelter serving that community. Instead, dogs have long lived on the beach where they are fed largely by tourists and vendors who feed them scraps. Beginning in 2007, Animal Balance began sterilization and releasing the dogs. If a local or tourist wants to adopt a dog, they tell one the vendors who contacts a local rescuer to facilitate the adoption. They use the beach as the adoption center and, by all indications the system works well. In fact, the vendors have become fiercely protective of the dogs and are a bulwark against government overreach (i.e., round up and kill). The same has been true on all the other islands which have endorsed the sterilization and release of dogs, even after initial opposition. All report that dog safety has improved even in large cities: they are healthier, roam less, and live longer. Some of the islands also report an increasing number of sedate, plump community dogs that are increasingly moving into homes.

According to one report,

Once the packs of males stopped chasing the in-heat females, we saw that the dogs started to hang out in front of their favorite person's home more. People were interacting with the dogs more, slowly the dogs spent more time around the house. The people started treating 'their dogs' for parasites, then they could come inside.

Public Safety

While this evidence suggests that this approach benefits the overall well-being of the dogs, how does it impact the safety of the public? In fact, one of the biggest concerns relating to the re-release of street dogs pertains to the perceived threat such animals pose to humans. Historically, opponents of sterilization and release for community cats also cited a laundry list of public health threats that failed to materialize. But what about for dogs? Here, too, there is cause for optimism.

Initial data from the Samoa experience shows a decline in the number of dog bites after the dog sterilization and release campaign. While the exact cause of this decline has not been specifically studied, officials point to a variety of factors: the obvious effect of neutering on dog behavior, a decrease in behaviors associated with mating such as roaming (that decrease chance encounters with humans and increase human tolerance), an increased respect for the dogs due to the positive role model of rescuers which results in kinder treatment and therefore less conflict, and the impact of dog behavior and interaction training of locals by rescuers that often accompanies these efforts. Whatever the cause, the positive impact on public safety has been profound, causing public officials, including agriculture and health departments, initially opposed to the idea of sterilizing and releasing dogs to now embrace it. Said one: "everyone is now sleeping better at night and so are performing better in the day. Having lived through it, I can agree, not having to listen to the dogs barking, fighting, mating all night long makes everyone's life quality better."

Of course this is preliminary data, but all indications so far point to success: "by sterilizing the dogs there are multiple knock on effects; the social structure of the pack changes... the relationship between the local people and the dogs change and they become closer as they learn more about each other and finally community perspective of the dogs as annoying and a nuisance disappear."

It is also interesting to consider that many of the communities in the United States complaining about the presence of street dogs none-the-less lack a coordinated and sustained effort to address them, while animal rescuers, concerned about such dogs but loathe to the idea of rounding up and killing them, feel stymied in their ability to assist such dogs due to a lack of resources for fostering and rehoming, especially where the local shelter is ineffective or nonexistent. Sterilizing and releasing dogs provides a middle ground that serves the interest of both groups--a way that local government can realize the untapped potential of local animal lovers and animal welfare NGOs that are willing to help, but unwilling to kill. This assistance can not only translate into fewer dogs over time through lack of reproduction and the inevitable adoption of some dogs that will occur once such animals are in the care of rescuers, but a decrease in perceived "nuisance" behaviors as well. Often, it also means transferring costs from the public sphere, the taxpayer, to the private, philanthropy. For the dogs, for the rescuers, and for local governments otherwise content to lament but ultimately do little to actually address the issue, such an approach is a win-win-win.

Public Acceptance

Another argument against sterilization and release of dogs is the claim that citizens will never tolerate the presence of community dogs. Not only do the experiences cited in places where this approach is already working prove otherwise, but so, too, does the history of sterilization and release of community cats, which, when first introduced, was opposed for the same reason and ultimately proved false.

Some suggest that the public will not accept community dogs by noting that the public's attitude toward community cats is relatively recent, citing surveys from the 1970s which claimed that the number one complaint of mayors were animal nuisance calls. But drawing conclusions about what should be done about community dogs from studies about nuisance animal calls 50 years ago is problematic, not only because the inferences drawn from the data failed to adequately account for the nuances in public attitude motivating such calls, but the fact that, at least when it comes to community cats, the conclusions drawn from such studies no longer reflect prevailing public sentiment. And it is these changing attitudes towards community cats which provide so much hope for our ability to foster tolerance for community dogs where needed to protect their lives from regressive public agencies.

Indeed, even if one could argue that most people wanted animals rounded up in the 1970s (as opposed to the loudness of a vocal and intolerant minority which is much more likely), today, well over 80% of Americans surveyed think community cats should be left alone if the alternative is impound and killing and three-fourths believe it should be illegal for shelters to kill cats (and dogs) if they are not suffering. There are no doubt many factors that have influenced the changing perception and increasing tolerance for community cats among the general public, but perhaps none more so than changing attitudes within the humane movement itself.

No doubt many prior calls to animal control authorities were frequently motivated by a belief--long perpetuated by the sheltering industry--that homeless cats were better off dead and that the "responsible" thing to do was to report such animals to those tasked with rounding them up: the local pound. How many people cited in 1970s studies as having made animal "nuisance" calls were in fact reporting the presence of community cats to the animal control authority because they were concerned with the animals' welfare and had been schooled to believe that reporting such animals was in fact the "humane" thing to do?

For those complaints which were motivated by genuine intolerance, we cannot discount the role that fear mongering by groups such as the Humane Society of the United States played in stoking fears towards such animals through their spread of misinformation about disease and public safety; misinformation that inflamed public prejudices, encouraged intolerance and which justified impound and killing. With groups like HSUS publicly advocating that, "ownerless animals must be destroyed. It is as simple as that" and encouraging a local prosecutor to arrest and jail community cat caretakers, calling TNR for community cats "inhumane" and "abhorrent," should it come as a surprise if some members of the public reflected equally heartless, regressive views? By that same logic, now that TNR has moved beyond controversy within the humane movement and among the public, what reason is there to believe that the humane movement itself does not likewise hold the key--through education--to fostering greater public acceptance of community dogs?

In other countries, local merchants and residents who initially asked public officials "to do something" about the dogs (i.e., round up and kill) have, post sterilization, become the dogs' most ardent defenders. Like the U.S. experience with cats, it is not necessarily the dogs people object to, but their behavior. And as with cats, sterilization has immediate and profound benefits in that regard. Now when a clinic is set up, organizers simply pass out leashes, collars, rope and, as necessary, traps and the community comes together to get community dogs to the clinic. Residents also help with any aftercare when the dogs are released following surgery. In short, people's views will change, and institutions can be reformed, when a better, kinder way is found and promoted.

Legality

That leaves one, last objection: that sterilization and release of dogs is illegal. Some argue that state or municipal leash laws might preclude such programs, or that sterilization and release of dogs would constitute abandonment, the last being an argument once made against such programs for community cats. Of course, these arguments assume, erroneously, that laws cannot be changed to meet evolving needs or to reflect newer, more humane values. But that aside, can our existing legal framework accommodate the sterilization and release of community dogs? As an attorney, former prosecutor, and former head of animal control who used to enforce state animal cruelty and abandonment laws, I believe the answer is yes.

Most states define abandonment, in one form or another, as "the leaving of an animal without adequate provisions for the animal's care." The basic premise of sterilization and release program, by contrast, is the opposite: to provide care for animals already abandoned by someone else.

Sterilization provides for the dog's health, prevents breeding, reduces competition associated with intact males, reduces roaming which could lead not just to more encounters with humans but more danger for the dog, and improves the animal's ability to not only survive but thrive. Especially if sterilization and release programs include supplemental care, anti-cruelty laws should not be construed as coming into play.

As another prosecutor has noted: abandonment "is directed at those people who dump their pets and those individuals who move from an area and leave their pets behind. If an animal is returned to the area where it is being fed, it would be a greater injustice to find that these animals had been abandoned so that no action to spay/neuter the animals would be taken by anyone."

Second, abandonment and leash law statutes require the person to be the "owner" or have care and custody for an indeterminate period of time. This is not present in sterilization and release programs. The community dog caretaker would exercise custody only for the purpose of taking the dog to the veterinarian, at all times presuming the animal's re-release.

Third, public policy in many states encourages and promotes efforts to reduce the suffering and death of animals, precisely the premise behind sterilization and release programs. State law, for example, declares it "to be the policy of New York State that every feasible humane means of reducing the production of unwanted puppies and kittens be encouraged" despite also having a law prohibiting abandonment.

Finally, any attempt to apply an abandonment statute to a community dog group would violate the constitution's requirement "that a penal statute define the criminal offense with sufficient definiteness that ordinary people can understand what conduct is prohibited." To apply anti-cruelty laws to community dog caretakers who are helping the dogs not only makes no sense, it would violate the constitution on grounds of vagueness.

A Bridge to a More Humane Future

All this said, I am not advocating sterilize and release over adoption into a loving home, just as I do not advocate it for community cats who are social with humans over adoption for those cats. Rather, I am advocating this approach only as an alternative to killing or doing nothing at all. In other words, if community "leaders" refuse to hold shelter leaders accountable and reform the shelter and instead advocate for things like helicopter gunships or round up and kill campaigns as they have in Dallas, sterilize and release provides a humane alternative. In addition, if animal lovers and rescuers in a community can be empowered to sterilize such animals, it would reduce the birth of feral puppies and improve the lives of dogs, while promoting neighborhood tranquility and public safety. Isn't that a vastly preferable option to doing nothing or mass slaughter?

If a pound is going to kill community dogs, if rescuers are not going to find them homes, if robust transfer programs are not in place to get those dogs to a community where they could find homes, they, like the dogs in the Dominican Republic and cats in the U.S., should realize all the other benefits that would come of sterilization. They can always be brought into the shelter when there is capacity. They might be placed through a rescue group or directly off the street. Or they live as community dogs.

In fact, I also believe that communities should consider sterilization and release for dogs while shelters are undergoing reform in a bid to become No Kill as a stop-gap measure to eliminate killing just as we do for community cats. Instead of the ubiquitous five or ten years plans to No Kill, which are little more than delay tactics or money grabs, the animals could be sterilized and released (and fed) while the shelter works to improve processes, reduce intakes, and increase capacity over time, without any interim period of killing.

Of course, once shelters are fully reformed, once we live in a No Kill nation, sterilization and release wouldn't be the first choice for community dogs, just like it does not have to be for community cats who are social with people: redemption and adoption would be. It would and should, however, remain a choice, because killing should never be a choice at all.

Photos of the Dominican Republic courtesy of Emma Clifford, Animal Balance. Jennifer Winograd contributed to this article.