An intensifying coastal storm, nicknamed "Snowquester," was plastering the Mid-Atlantic states with 1-to-2 feet of heavy, cement-like snow on Wednesday, and is forecast to crawl northeastward, bringing the threat of multiple rounds of coastal flooding to an already vulnerable New Jersey shore and coastal New England, along with rain and snow.

While the prospect of heavy snow in places like Washington, D.C. and New York City has garnered most of the headlines, coastal flooding may end up having the most severe and long-lasting impact. Areas that are most vulnerable span from Delaware northward to the picturesque towns along the Massachusetts coast, where as many as six high tide cycles could yield severe beach erosion and coastal flooding, due to a prolonged stretch of gale force onshore winds and high seas on the order of 25-to-30 feet.

The storm comes about a month after a February blizzard that hit the Massachusetts coastline, causing widespread moderate to major coastal flooding. That storm led to the surreal sight of seawater careening down the snow-laden streets of Winthrop and Scituate, Mass.

The damage from that Feb. 9 storm, combined with the extended timeframe of this event, is heightening coastal flooding and beach erosion concerns across eastern Massachusetts, according to the National Weather Service (NWS).

On Wednesday morning, the NWS warned coastal residents to prepare for a long duration coastal flooding event, as the storm’s center crawls eastward into the Atlantic, then edges north, closer to New England, before finally moving away on Friday or Saturday.

“Current trends are ominous,” said a technical discussion published by the NWS’ Boston forecast office on Wednesday morning. The NWS said the observed storm surge height in Boston is already running higher than what computer models projected, indicating that the threat of flooding may be more significant than previously thought.

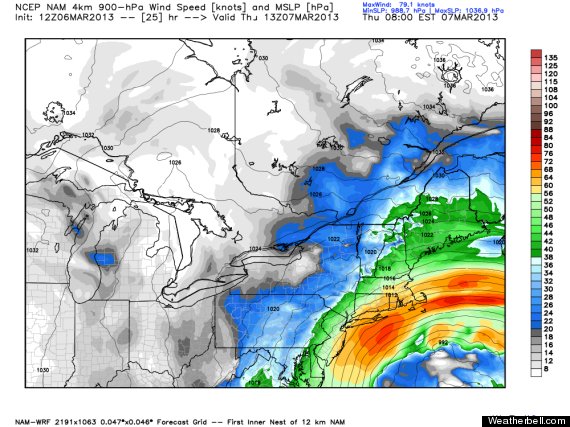

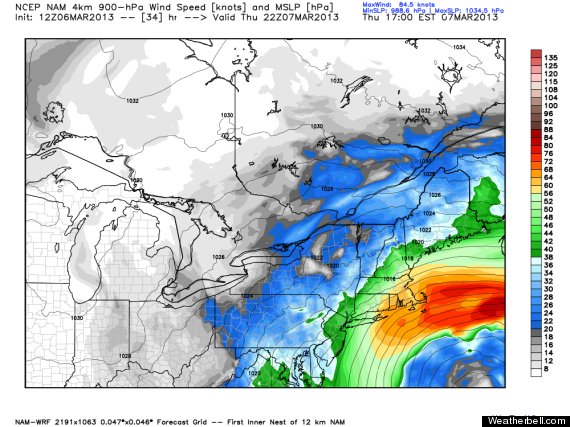

These images show a computer model forecast of surface air pressure and winds aloft for Thursday morning (top), and Thursday evening. The bright red colors indicate the strongest winds, blowing onshore into southern New England. Note how little the storm moves during the period. Credit: Weatherbell.com

The high tide that is of greatest concern along the eastern Massachusetts coast will occur on Friday morning, between 7:30 and 9:00 a.m., when moderate to major coastal flooding could take place, although moderate coastal flooding may occur as soon as the Thursday morning high tide.

The NWS is forecasting that some coastal areas may be inundated with 2-to-4 feet of water during the Friday morning high tide, and large waves may cause damage to some coastal homes and businesses in eastern Massachusetts.

Coastal flood warnings are also in effect in New York City and along Long Island Sound, as well as along the New Jersey and Delaware coasts, with “widespread moderate tidal flooding” expected along the Atlantic Coast in New Jersey and Delaware, with some areas of major flooding possible during the early Thursday morning high tide. The high winds and pounding surf may take a further toll on the Jersey Shore, which absorbed a devastating blow from Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

The forecast storm tide at Cape May, N.J., is actually slightly higher than it was during Hurricane Sandy, at a record 9 feet above Mean Lower Low Water, which would be 1.2 inches higher than during Sandy.

Because of sea level rise due to warming ocean temperatures, melting polar ice caps, and sinking land masses, along with other factors, coastal storms such as this one are already more damaging than they used to be just a few decades ago, and this trend is expected to continue, according to recent scientific assessments.

Higher sea levels provide a higher launching pad for storm surges from hurricanes and nor’easters, making it possible for relatively weak storms to cause major damage. In Boston, the top five highest storm tides — which is the combination of the tide level and storm surge — all occurred during nor’easters.

According to research by Climate Central scientists, on Nantucket Island, where coastal flooding is anticipated from this storm along with winds as high as 55 mph, the sea level has risen by about half a foot during the past 50 years.

According to the draft National Climate Assessment report released in January, even without any changes in storms, the chance of what is now a 1-in-10-year coastal flood event in the Northeast could triple by 2100, occurring once every 3 years, due to rising sea levels. Climate Central research shows that the odds of a 100-year flood or worse in Boston Harbor by 2030 would be 23 percent with sea level rise from global warming. Without global warming-related sea level rise, that figure would be 9 percent. The bottom line is sea level rise multiplies the odds by 2.5 times.

Weather Gridlock

One reason why this storm is such a significant coastal threat is that it’s forward movement is limited by a traffic jam of weather systems over the North Atlantic, known as a “blocking pattern,” which can help result in extreme weather events.

The blocking means that the storm is likely to slow its forward motion as it moves up the coast, and some computer models show it lingering off Cape Cod for about two days, which would bring more damaging impacts to southeastern New England.

Blocking patterns are a key ingredient in major East Coast winter storms, and a formidable block was in place when Hurricane Sandy roared ashore in New Jersey in October, bringing with it a record storm surge that inundated wide swaths of the coastline, particularly from Atlantic City northward to Long Island.

Some studies have shown possible links between rapid Arctic warming and its associated sea ice loss and an increase in blocking patterns in the Northern Hemisphere. Strong blocking patterns have been linked to several noteworthy extreme weather events, such as the deadly 2010 Russian heat wave and Pakistan floods, the 2003 European heat wave, and the March heat wave of 2012 in the U.S.

A new paper in the March issue of the journal Oceanography by Cornell and Rutgers University researchers argues that there may have been a link between Arctic warming and Hurricane Sandy’s eventual track and strength, as well as with other storms that occur during similar circumstances.

“... There is increasing evidence that the loss of summertime Arctic sea ice due to greenhouse warming stacks the deck in favor of larger amplitude meanders in the jet stream, more frequent invasions of Arctic air masses into the middle latitudes, and more frequent blocking events of the kind that steered Sandy to the west,” the paper said.

However, other scientists working in this field say there have not been statistically significant increases in blocking patterns detected, and it's an area of active research.