Anti-Semitism, like Mideast tensions, isn't new.

There have been periods in history when Jews, Christians and Muslims lived in relative peace, though undercurrents of hostility remained. One such time was Jerusalem, 1192, during the Crusades, when the three religions held a fragile truce.

That historic moment attracted author Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, an 18th-century Enlightenment philosopher, who promoted religious tolerance in Nathan the Wise, now off-Broadway at the CSC.

It was a radical move; many of his writings on the subject were banned or censored by the authorities. His friendship with eminent philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, on whom Nathan was based, was equally rare.

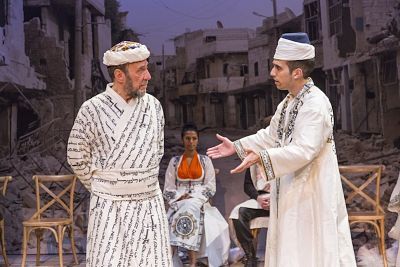

At the play's heart is a plea for acceptance. So when the ruling sultan asks Nathan (F. Murray Abraham), a wealthy Jewish merchant, a leading question, it could have serious repercussions.

"Which religion is the most beloved by God?" he queries.

"If I say the Jewish way is the only way, I risk his wrath," Nathan muses. "If I deny my race, he'll ask me, 'why aren't you a Muslim?' There must be another path."

Nathan is not only wise but politically astute. Fortunately, the sultan (Austin Durant) is a reasonable man, and the parable Nathan relays keeps potential punishment for the Jews at bay. It also makes an impassioned argument for mutual respect for all religions.

Indeed, in an era of virulent anti-Semitic caricatures and treatment, Lessing portrays a Jew who is humane and generous. The play also records the cruelty of Christian fanatics, while staging dramatic interplay among the sultan, the Knight Templar (Stark Sands) and Nathan.

The three, including Nathan's daughter (Erin Neufer), will see their destiny played out in an emotional roller-coaster ride. Themes of friendship, the mystery and relativism of God and the nature of acceptance are explored en route. Its thesis -- then and now -- is compelling.

While interesting, Nathan the Wise, a story of familial secrets, is a bit contrived. Still, its solid cast, led by a centered Abraham, carries it off.

Tony Straiges' set is economical, save for a confusing backdrop, a photo of satellite dishes atop abandoned buildings; costumer Anita Yavich's robes and tunics, stamped with the language of the wearer, are evocative.

Directed by Brian Kulick and adapted by Edward Kemp, who shortened the work, Nathan the Wise doesn't shy from religious cruelty, but promotes an important ideal.

Lisa Dwan's Beckett Trilogy -- Not I, Footfalls and Rockaby -- at NYU's Skirball Center, is far more abstract in sensibility.

Dwan, a gifted Beckett performer, boasts an impressive vocal range and control. The trilogy is a musing on the persistence of consciousness against all odds, as well as a realization that suffering is endemic to the human experience.

Beckett's exploration of the space between life and death can be unnerving. He invites us to experience the elasticity of suspended time -- waiting for the inevitable end. In the hands of an accomplished actress like Dwan, coached by Beckett interpreter and muse Billie Whitelaw, it is a haunting experience.

She brings dexterity to each character, while sustaining specifically crafted moments with grace.

Aided by lighting designer James Farncombe and sound designer David McSeveney, Dwan's performance is memorable.

Photo: Richard Termine