On April 1st, HollabackPHILLY (a project of Feminist Public Works) launched a series of anti street harassment ads in the Philadelphia public transit system, including subway car interiors, bus shelters and subway station platforms throughout the city.

This is an expansion of the small but high-impact pilot campaign we ran last year, that quickly went viral online, attracting significant local and national press. Our goal with both campaigns was to familiarize the public with the term "street harassment" (gender-based harassment by strangers in public spaces) and define it as a solvable problem, as opposed to an inevitable "fact of life." However, this year we took it a step further, employing some killer messaging strategies that we hope will generate even deeper conversations.

Last year's ads were almost exclusively definitional. For example, since most people are unfamiliar with the term "street harassment," the below ad links the term with specific examples.

Street harassment is often minimized as a "compliment," and the below ad aims to start conversations around that issue, while linking the term "street harassment" to "unwanted comments."

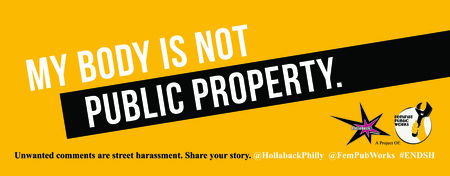

This year's new set of ads build on last year's definitional work by broadening and expanding it. For example, the below ad distills why street harassment is a problem: harassment communicates that people's bodies are open for public commentary, and limits our right to move comfortably through public spaces.

This next ad highlights the seriousness of the issue, making a complete break from the common minimization of street harassment as "just a compliment" or "annoying." Street harassment can make people feel unsafe in lots of ways -- for example, street harassment is unpredictable. An example we hear all the time is how a simple, "Hey, beautiful" can quickly turn to, "Stuck up b*tch!" or worse when ignored. Never knowing what might come next means that even relatively mild statements can make people feel unsafe.

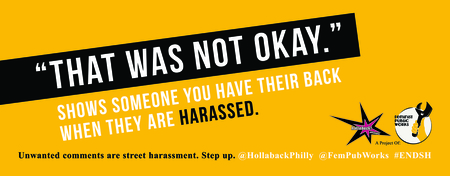

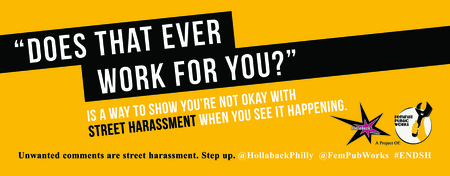

Other ads take it a step further, straight into bystander intervention. The following two ads give specific examples of what a person can say to support someone who has been harassed, or how to call out someone who has just said or done something harassing:

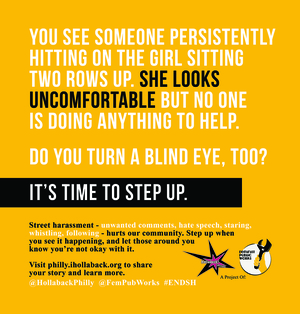

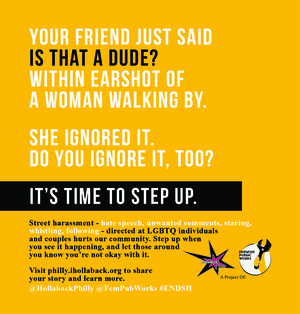

The following ads give examples of harassing statements, and pointedly shift the responsibility to respond from the victim to the bystander:

Some of the ads focus on calling out a stranger on their behavior or giving support to a victim after the fact, while others focus on how we can react when those closest to us -- our friends -- are engaging in harassing behaviors. All of these ways of intervening are powerful and important. If we want to see social change around street harassment, we need to start building up social pressure both out in public among strangers, and privately within our inner circles. This means it's time to start stepping in when we see harassment happening, because simply being a person who doesn't harass is not good enough. According to the principle of social proof, our silence when we see harassment happening to others is easily read as acceptance, and reinforces in the harasser's mind (as well as others witnessing the behavior) that the harassment is socially acceptable.

The shift from individual responsibility to a community sense of responsibility is commonly known as a bystander intervention approach, which has become a gold standard for gender-based violence prevention. Viewing the problem of street harassment as a shared responsibility is a revolutionary shift, not only because our culture emphasizes individuality at every turn, but because this shift puts the focus squarely on the harasser. If we're active bystanders, ready to intervene, it's because we see someone (the harasser) doing something wrong. What the victim is doing or wearing is not even part of the equation.

To get technical, this campaign works to establish a new injunctive social norm. Injunctive social norms regulate our perceptions of which behaviors we consider socially desirable or undesirable. There is another kind of social norm, called "descriptive social norms" which describe our perceptions of those behaviors we see as typical or normal. We avoided focusing on descriptive social norms in this campaign, because they tend to backfire by reinforcing a perception that the behavior the campaign is fighting against (in this case, street harassment) is in fact widespread, and therefore acceptable. One of the most famous cases of this happening is the famous "Crying Indian" anti-littering campaign in the 1970s, which actually resulted in more littering by reinforcing the perception that everybody was doing it.

One of the keys to successfully influencing injunctive norms through advertising is to be specific. Just telling people that a behavior is wrong is not the same as giving them the tools to change it. Our campaign ties the problem of street harassment to specific situations, like "Your friend just said, "Is that a dude?" within earshot of a woman walking by and. "You see someone persistently hitting on the girl sitting two rows up." We also suggest some possible responses, like "That was not OK," and, "Does that ever work for you?" to start getting people thinking about specific ways they might feel comfortable intervening in the moment.

While we work to broaden our messaging through social change strategies, the bystander-focused ads circle back to deepen the definitional work as well. The ads above delve into how street harassment specifically affects trans* women, the ever-prickly issue of telling people to smile, and the harassment of queer couples. Street harassment is an incredibly complex issue that doesn't lend itself to a simple, watered-down slogan. Our campaign aims to be as specific and direct as possible, while making space to open up conversation.

We would love to hear your feedback on this campaign. Share your thoughts here.

If you're interested in learning more about messaging strategies, check out my blog, Feminist Messaging Project.