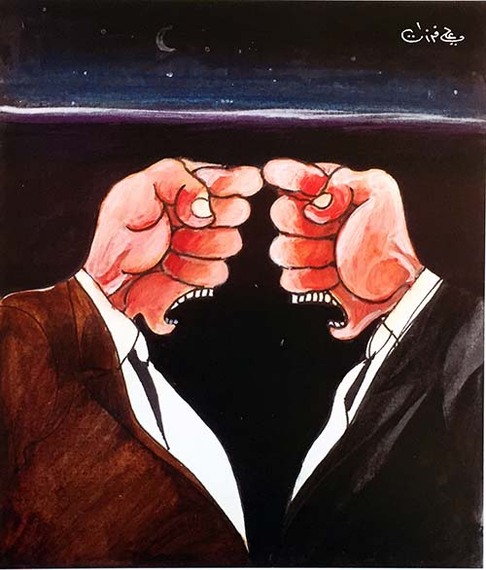

Get on the wrong side of the powers-that-be and you could end up with smashed hands, broken fingers, a bruised face, a bleeding body or worse.

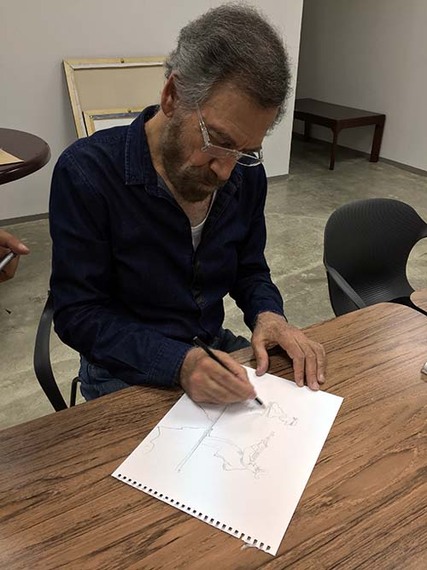

That's true of caricaturists who mock their regimes, and it's what befell Ali Ferzat when his scathing illustrations took aim at Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad and the country's ruling elite.

"My illustrations were such that even if I drew one line, the authorities were terrified of the impact," recounted Ferzat, in self-exile in Kuwait four years after thugs beat the daylights out of him and left him on the side of the Damascus airport road.

News of the incident and pictures of him in hospital went viral on social media and in traditional news outlets.

He was banned several times in Syria when he was at a government-run paper, he said of the precarious balance he tried to maintain, adding that freaked out authorities would over-interpret what every line, every dot, and every potential nuance meant.

The tipping point came in August 2011 as the "Arab Spring" snowball began growing, and with the outbreak of war in Syria when he felt compelled to take direct aim at the president.

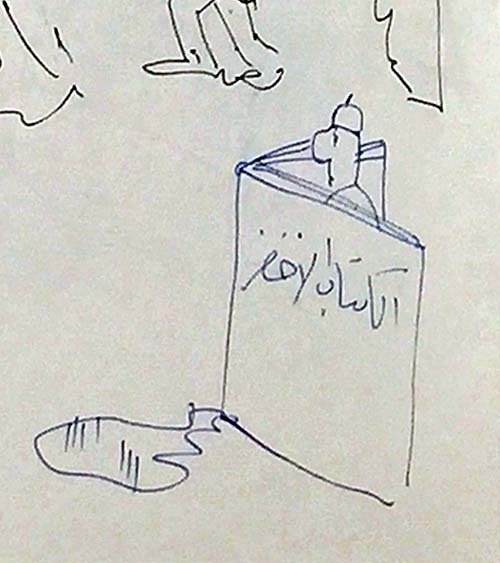

Ferzat, who had been drawing in state-controlled newspapers and had published his magazine, "Al Domari" (the lamplighter) -- which was eventually shut down because of its critical content -- was snatched as he walked home at night and "taught a lesson."

The unrepentant caricaturist was hospitalized, eventually recovered and left his homeland, but continued to draw -- his pen and tongue as sharp as ever.

"I swear I'll never let them rest," he said defiantly. "Imagine, they said the picture of the drowned (Syrian refugee) toddler Eylan (on a Turksih shore) was a fabrication."

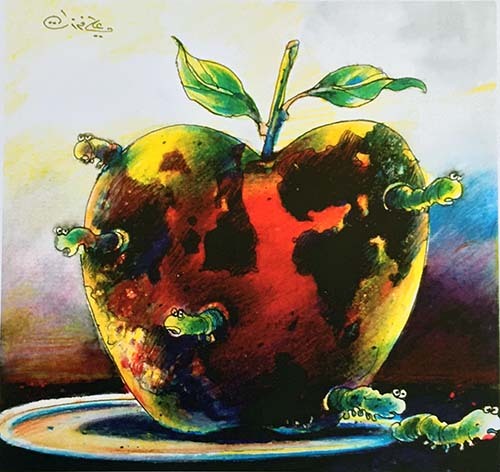

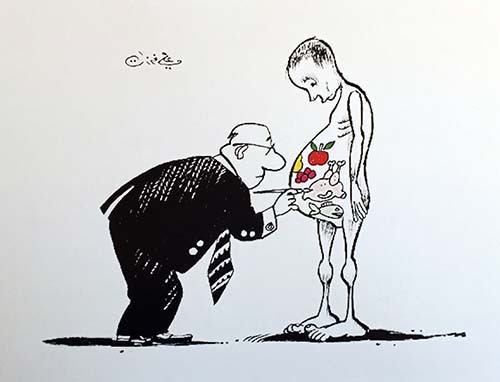

Ferzat's creative juices are stirred by his antipathy to dictatorships, to the military's power run amok, and to corruption in general.

He feels it's his moral duty to skewer "the nasties" and rally to the cause of the underdog, in his country and the Arab world. He is most ticked off by military leaders.

He insists the harm his caricatures cause isn't personal, but against an issue or unacceptable practices, and he provides proof to make his point.

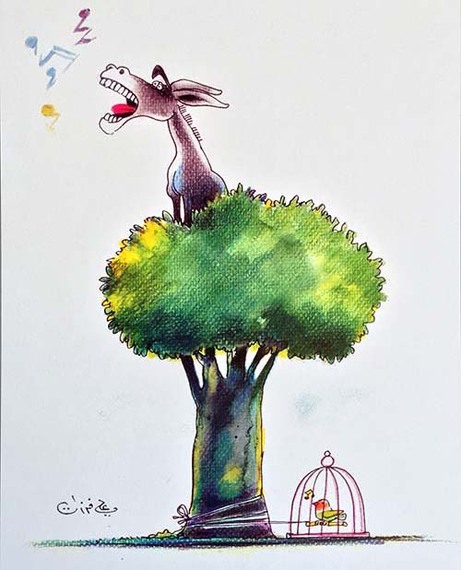

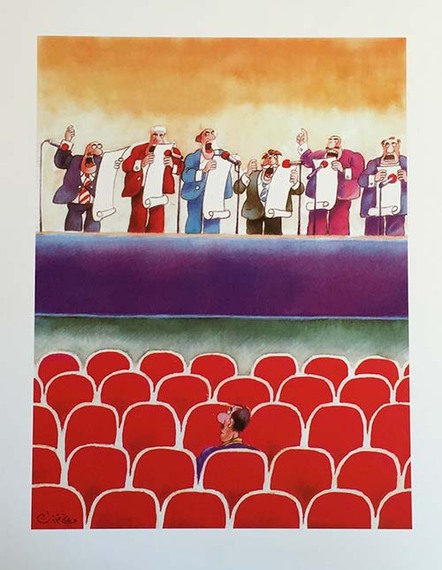

"The fewer the words in a caricature, the more universal it is," explained Ferzat of his medium. He relishes recounting his adventures in countering the regime.

To him drawings devoid of words trigger analysis and help expand readers' thought horizons to discover meanings, which he said were a pleasurable experience.

"My work titled 'no comment' means I leave it to people's imagination, but there's usually a goal and a message," he explained.

In 1983 he worked for a paper in Abu Dhabi called "Al Wehda" (The Union) and asked the editors to use an older drawing while he was on vacation.

They selected one of an upturned hand with a table in the palm and the tips of the fingers drawn as Arab men with different national headdresses. A sign on the table said "conference" and the cuff read "U.S.," implying American manipulation of Arab leaders.

The publication of the caricature, which he re-drew on a white board in Kuwait during a conference and workshops organized by the Nuqat Foundation, had coincided with an Islamic summit in Abu Dhabi and about which he wasn't aware.

It was taken as an insult and he was summarily fired.

Ferzat said he targets dictatorial regimes and has been banned from Iraq, Libya, Jordan and Oman. He once drew a Libyan citizen peeing against a wall fashioned after the late flamboyant leader Muammar Qaddafi's famous "Green Book."

"I want to illustrate our painful reality, the leaders and their positions regarding what's happening in the Arab world," he said.

On how he selects topics for his illustrations, Ferzat said artists are often bombarded by several notions and ideas at once but shouldn't be tempted to grab them and turn them immediately into illustrations.

"Everyone has an internal compass to direct him/her and that's how it works with caricaturists," he said.

There should be a thought process, development of the message to be delivered, and proper contextualization.

"I'm not beholden to the daily grind of the media," he explained of his modus operandi. "If I'm contracted by a paper, I send an advance reserve of 15 pieces, usually generic topics, and then do dailies events."

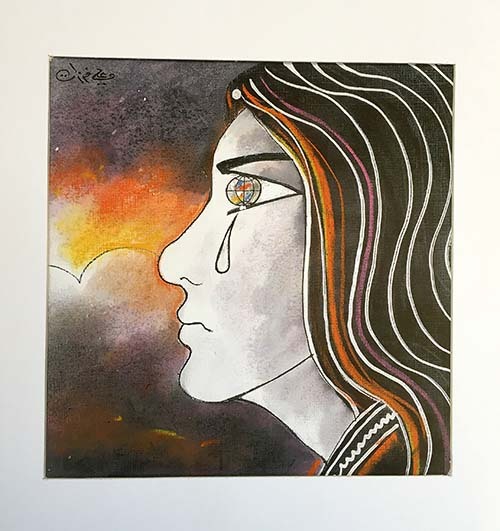

In 1996 Ferzat had an exhibition of his illustrations as paintings that sold for world-class prices. They were no longer just caricatures in newspapers.

"A painting must be a beacon of light and hope and the skill is in the distribution of color," he said.

As he showed workshop participants his illustrations and paintings, he demonstrated how color played a big role in setting the mood.

"Caricatures can reflect sad events with an emphasis on drama and tragedy: I had black and white illustrations for decades and later began to transform some of them into color, with some adjustments" he noted.

Sometimes he draws on black backgrounds with white correction fluid to reflect a painful reality.

Ferzat was influenced in his youth by caricaturists in Egyptian weekly magazines that his father brought home and later realized he had a satirical spirit before he began drawing.

The mission of art is a humanitarian one, he insists, and for caricaturists there's job-related work and there's creativity. He feels he's drawing for humans, not a group or an institution.

Not all is depressing, according to Ferzat. Caricatures have to have an element of hope for a better life.

"Most of my illustrations have hope and optimism. The bitter satire is to make a point; as an artist I can't keep quiet," he said.