Last April, as part of Democracy Spring the two of us marched from Philly to D.C. with four game-changing demands for Congress: Get big money out of politics, ensure voting rights, improve voter registration, and reverse Supreme Court rulings that allow private wealth to defeat citizens' right to a meaningful political voice.

Although virtually ignored by corporate media, some in Congress heard our voices--most notably Representative John Sarbanes (D-MD) who immediately collected roughly 100 Congressional signatures on a petition to hold hearings on our demands.

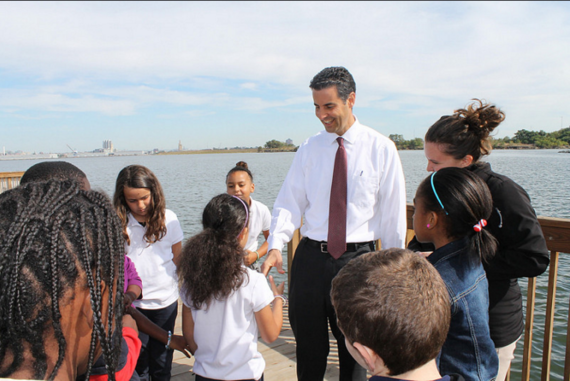

Needless to say, John Sarbanes is a hero to many, shining the light on the mother of all issues: democracy itself. Recently we felt honored to chat with him. Below is the first half of our conversation (look for part two coming soon). Here, we discuss how money affects legislation and the emerging grassroots movement to fix our democracy.

Congressman Sarbanes: I think we all agree that democracy is the gateway issue. If we can't create a strong, vibrant democracy, we're never going to get the policies we want--or the public's respect.

I am gratified that Democracy Spring wasn't--and your upcoming book isn't--just another articulation of the problem. If we don't put forth practical solutions, people's anger can take some very dangerous directions, as we have been seeing.

Adam Eichen: A novel thing is happening now. There are ballot measures in more than a dozen states to reduce the power of private money in politics, including in your district of Howard County. What do you think of the ballot initiative process to reform our campaign finance system?

Sarbanes: I am tremendously excited about the effort in Howard County. Here, the questions to the public are: "Are you ready to take the power back from special interests? Are you ready to make it possible for everyday citizens not only to have their voices heard but to get into the ring themselves and run for office? To be competitive even if they don't know a lot of people with a lot of money?"

To distill things down: This is about power. When people feel powerless, as so many do, that generates frustration, anger, and cynicism, where so many people either just want to grab a pitchfork or drop their heads and walk away from our politics and our democracy. That's the worst thing that can happen because then extremists, demagogues, and others can rush in and fill that space. And certainly we have seen this play out across the country and in the presidential campaign.

So, we need solutions that people can look at and say: "I see myself in this, I see that my voice matters, I see that I can have an influence over my democracy and my politics." And if we put that in front of people and they believe in it, I think we can start moving in a very, very positive direction.

I have been encouraged by the ballot initiative victories last November in Maine and in Seattle. If we can win in Howard County, it will make another very positive statement about where we can go with this kind of reform.

Frances Moore Lappé: How do you see the connection between the crisis of money in politics and voting rights?

Sarbanes: They go hand in hand. We have to protect people's right to vote and we have to protect people's right to have their vote mean something.

The first part of that has to do with protecting access to the ballot box, where there's been a widespread assault. In Montgomery County, Maryland, there was an attempt to eliminate an early-voting center largely used by minority populations. And if that's happening in one of the most progressive counties in one of the bluest states in America, we all know it's happening in other places.

But access to the ballot box isn't the only issue with voting. A conscious voter could well say to themselves, "Wait a second, if I vote, and all I'm being asked to do is choose which of two candidates I send to Washington to work for somebody else, for the special interests, why bother?"

In other words, the undue influence of concentrated money in our politics degrades the value of the franchise because you can't assure people that the person for whom they vote will represent their views once in Washington or their state capitol. The fact that the last national election (2014) produced the lowest voter turnout since 1948 in part is attributable to this calculus.

Lappé: So Congressman, in your journey, at what point did you realize that no other significant reform is possible without these deeper democracy reforms?

Sarbanes: Well, there were two things. One was an instinct, which kicked in right at the beginning of my time in Congress. It happened between the time I was elected and the time I was sworn in. A large industry player in my district approached me. They said, "We'd like to pull something together for you" implying a high-dollar fundraiser. And my instinctive reaction was: "Wait a second, I am not sure I want to go down this path." So I stepped away from it.

But that initial reaction was something I then built on and it encouraged me and compelled me to really make a study of how money operates in Washington and how it finds its way to members of Congress, to candidates, to committees, in a way that distorts public policy.

The more I looked at it, the more I realized how pervasive that influence is. It's subtle--not like some quid pro quo transactional corruption. It's human nature to lean in the direction of those who support us.

This led me to the decision, a certain number of years ago, to give up all PAC money from all sources, which turned out to be unique in the 2014 election cycle.

I also started connecting the dots between the influence of big money on substantive policy issues. The environment is an obvious example. Our inability to move aggressively on climate change legislation can be tied to the tremendous influence of the oil and gas industry on Capitol Hill. Oil Change International and the Sierra Club did a study a couple years ago and determined that the oil and gas industry was getting a 5,800 percent return on its investment in lobbying and campaign contributions. So, while they may be spending hundreds of millions of dollars on campaign contributions, they are getting billions of dollars of return in the form of tax subsidies, and other supports on Capitol Hill.

If we could unhook ourselves from the dependence on that particular industry, our ability to make clear-headed judgments about environmental issues would be significantly enhanced. You can find dozens of other examples, too. Take the pharmaceutical industry's influence in Washington, which has prevented us from allowing the Medicare program to negotiate drug prices. This has resulted in costs of tens of billions of dollars a year to taxpayers in inflated expense for the Medicare program.

So the list goes on and on, of how the big-money special interests in Washington are distorting public policy, and moving it in a direction that isn't respectful of the public's needs.

Eichen: I am really curious, how do you compare the time you've spent in Congress with that of your father Paul Sarbanes, who was in Washington as a Congressman and Senator for over forty years?

Sarbanes: I will say this about my father's time: He got started in an era when big money interests were not metastasized the way they have in recent years. While you did have special interests operating, there was enough separation between them and lawmakers and the way the institutions functioned. The policymaking machine could still function reasonably well. And those interests were less aggressive, and, in a sense, were less bullying in the way they conducted themselves on the Hill.

What's happened in the last ten, fifteen years is that the money has become so entrenched, so powerful, that it dominates everything. It is almost as though policymaking happens inside of a superstructure of money and influence. And it's suffocating to democracy. It's suffocating to the institution. And it's suffocating to the people's aspirations of what their democracy should be.

That's why it is so helpful to be able to point to solutions happening at the state and local level. So you can say to people, "Look, you don't have to give up. Look at what they are doing in Seattle, Maine, Arizona, and Connecticut. They are taking the power back. They are reclaiming their democracy. And if we can do it at that level, we should be able to do it in Washington."