"Why do they hate us?"

THE AMERICAN PEOPLE:

LARRY KRAMER'S BLISTERING MAGNUM OPUS

by Lawrence D. Mass

"This is always history's greatest failure, its inability to believe what it sees, what, almost always, someone sees."

--Larry Kramer, The American People

There's a paradox inherent in historical novels. Though they tend to inspire stronger and more personal feelings than historical chronicles, the safety net of fiction renders those feelings less directly true. We know that Gone With The Wind was more imagined than actual history. The same is true of War and Peace. We can see our own lives in these great historical novels to an extent that's harder to do with documentation-heavy histories. But when we want to know the specifics of what actually happened in Russia and our Civil War, we look to what are considered authoritative histories rather than historical novels.

Consider the works of Larry Kramer. Though his first novel Faggots viscerally captures the bigger picture of a sex-besotted gay community unraveling around its inability to integrate sex with love, fictionalization of the characters and situations, even those that suggest real-life figures, facilitates a level of detachment from the actual history of that community in time and place. The same is true of The Normal Heart, his dramatization of the early AIDS crisis, as well as his farce, Just Say No, about Ed Koch and the Reagans. By fictionalizing and conflating these histories and their protagonists, the bigger issues can be perceived in sharper relief, and developments and personas may more vividly and persuasively emerge. "Novels are the private lives of nations" and "Fiction is history, human history, or it is nothing." Kramer quotes first Balzac and then Conrad in the two pages of epigraphs that open The American People. But there's nonetheless a price to be paid for fictionalization and dramatization. These works can no longer be claimed as authoritative history. This is the challenge that accompanies the literary and artistic achievements of Larry Kramer.

The American People is predictably commanding and passionate, its insights are stunning and endless, its narrative consistently compelling. But how much of the history it recreates is true? How much of it actually happened? Debates about fictionalization are among the greatest in all of literature and art, way too big a subject to try to resolve here. My suggestion is that we take The American People on its own terms -- as we do Faggots and even The Normal Heart -- as an extended evocation that reveals bigger truths than the historical details which in this or that instance and particular may be more a composite and fiction than accurate history. In the end, I have no problem with Larry Kramer's compositings, dramatizations and fictionalizations, even when they extend to my own experience, except when he asserts them to be "our history." Did Tolstoy proclaim "this is our history" for War and Peace? "It is not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less a historical chronicle," said Tolstoy. Did Margaret Mitchell declare Gone With the Wind to be an accurate history of the American South and the Civil War? "No, not a single character was taken from real life," admitted Mitchell in an interview. Is it right for Kramer to keep affirming of The Normal Heart that "this is our history"? To what extent will he do likewise with The American People?

Conversely, is The American People the War and Peace or Gone With The Wind of LGBT history? The American People is so many disparate things that comparisons will inevitably fall short. It's a Swiftian journey through an America we never knew; a Voltairean satire of American life and ways; a literary offspring of Gore Vidal's Lincoln and Myra Brenckenridge; a pornographic American history through the eyes of a Henry Miller; a Robin Cook medical mystery. It's a Sinclairean expose of American industrial and corporate skulduggery, and otherwise breathtakingly testimonial to the art of muckraking. It's a treasure trove of historical findings, especially of the history of sex in America -- of prostitution, communal living, of STD 's, of medicine and infectious diseases, of sanitation and health care, of medical and historical institutions, research, opinion, publications, figureheads and testimony. It's an ultimate coming together (pun intended) of the personal with the political. And it's the grandest telling yet of Kramer's own story.

There is one critical difference between The American People and historical novels like War and Peace and Gone With the Wind. With Russian history and the history of the American Civil War, a lot of what actually happened has been documented and chronicled, however incompletely. By contrast, most of the LGBT history that is the great preoccupation of The American People has to be deciphered, decoded and imagined, albeit in light of the arsenal of rare historical materials Kramer has mined. This is the great journey that Kramer has undertaken and the full measure of its achievement is difficult to determine at this juncture. What Kramer has done is the equivalent of, say, American history being recollected from the viewpoint of a Native American, a black person, a Jew or a woman. With other minority identities, however, there are more and better recorded histories extant than anything we might call LGBT history, a tragic legacy that Kramer is at greatest pains to decry and redress.

There are several premises crucial to The American People. The first is to understand where "the plague" came from, to locate what is suspected to be the "underlying condition" ("UC"). The journey begins with Fred (as in Fred Lemish, the Kramer character in Faggots) and a cacophany of experts, historians, scientists, researchers, miscellaneous commentators and including a kind of virion (virus analogue), most of these serving as alter-egos. As the journey progresses through every realm of history, including Fred's own and that of his Jewish family and community in America's home town, Washington, D.C., elements accumulate that are or seem to be contributory to the spread of disease. As Fred and company venture forth, they exude Kramer's in-depth fascination with and sophisticated knowledge of the intersections of science, medicine, history and sociology with every conceivable circumstance of sophistry, chicanery, wickedness, depravity and atrocity. They venture back and back and ever-further back to when the virion seems first to have wended its way via monkeys devouring each other; and before that to when the virion was looking for a host. Before they know it, Fred et al find themselves not only discovering earlier outbreaks of diseases that may have been contributory to UC, but ineluctably reconstructing nothing less than a very unorthodox and most definitely unauthorized history of the American people.

Ultimately, from a slowly brewing matrix of early American ignorance, arrogance, indifference, hatred and the 7 deadly sins, UC is revealed to be bigger and more ramifying and subsuming than anything imagined by even the most fanatical multifactorialists (those who emphasize the importance of co-factors in disease outbreaks). It becomes slowly clear that whatever else UC will turn out to be in Volume 2, it is also nothing less than the great swath of humanity and history that is the American people. All of it, the American people past, present and future, the novel tacitly suggests, was necessary for the plague to take hold and spread in time and place. Conversely, it's implied, had the American people been even somewhat less selfish, arrogant , ridiculous, stupid, bigoted, thieving, lying, hypocritical, marauding, pillaging, plundering, dumb and dumber, hating, hateful, murderous, mass-murderous and evil, one of recorded histories worst global catastrophes, the plague, might never have happened as it did. It's an unarticulated but spectacular premise that can be as difficult to swallow as it is to refute.

Just as you are witness to the burning of Atlanta and the sacking of Moscow and other battles in the otherwise personal, domestic and family dramas of Gone With The Wind and War and Peace, so you are witness through the personal accounts of Fred et al in The American People to officially designated landmark episodes of American history such as the Civil War and unofficially designated turning points such as the rise of the eugenics movement that helped spawn what became Nazism, episodes and events that have become otherwise so depersonalized by historians that we've lost our ability to appreciate them as three dimensional and its participants as flesh and blood; events and personages famous and infamous that have been desexed, otherwise whitewashed and often completely expunged from records and memory.

Kramer's narrative sardonically recounts so many examples and exemplars of egotism, of pomposity and religiosity, of religious cults and sects, of demented Jews and bigoted Catholics, of crazed Mormons and Baptists, of meanness, of stupidities and cruelties, of prejudices and oppression, of bullies and wusses, of fornicators and buggers, of people with plagues of various kinds, especially sexual, of blood and bloodletting and bleeding, of bloodbanking bunglings, of pus and sores and scabs, of bodily fluids, of odors and stinks, of waste management pollution and profiteering, of circumcision botchings, of the stigma of "illegitimacy," of incest (and plenty of it ), of hellish orphan life and orphanages, of the horrors of institutionalization, of eugenics, of involuntary euthanasia, of forced sterilizations and castrations by law, sanctioned and sometimes spearheaded by leading Americans including Teddy Roosevelt, John Harvey Kellogg, Henry Ford, Averill Harriman, John Foster Dulles and many others, of segregations, of massacres of slaves and Native Americans, of murders and murderers, of mass murders and mass murderers, of government backed edicts of hatred, of social diseases, of toxic home remedies, snake-oil cures and lifesavers, of the "real" history of poppers, of persecutions, of the violent suppression of sexual variance, of exterminations of admitted or suspected homosexuals, of concentration camps, of American collaborations with Nazis and Nazism, of the specifics of eugenical and Nazi medical experiments on children and those deemed genetically inferior, of starvations and cannibalism (and plenty of it ), of so much evil that incredulity can seem the only alternative to the otherwise continuous shock, horror, outrage and sense of genocidal tragedy. But it's just this incredulity on our part that Kramer most wishes to engage and conquer. The American People is evoking history, especially LGBT history but with it Jewish, Jewish-American and other American history, so that it's reach and its import for our lives and times and for future lives and times can be more rightfully and confidently prioritized for research, appreciation and mourning. Beyond all the particulars, Kramer's greatest hope and expectation is simply that the vast expanse of LGBT history that has been relegated, denied and otherwise lost to us finally will be claimed.

Another of the premises of this undertaking is that there have always been LGBT people. Though we no longer hear as much about the never-resolved sexual orientation debates that dominated scholarly discourse on homosexuality in the period that followed the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder by the American Psychiatric Association in 1973-74, they fell under the broad rubric of "essentialism" vs "social constructionism." Social constructionists believe that gayness is a modern concept given outsized importance by great social forces, especially capitalism and colonialism. Essentialists are those like Larry Kramer who believe that LGBT people have always been recognizable and identifiable; that we have existed as such throughout history; that there have always been transgender folk, bisexuality and homoerotic desire that would be as recognizable in Native Americans and early Puritans as they are today; that gay men have always cruised each other, have always had cruising areas, have always had names and labels, depending on the society, era and location. Responding to allegations and arguments that historical letters and documents and histories do not support these contentions about LGBT life in other times and cultures, Kramer continually affirms his sense of the internal and external censoring that revolved around all aspects of sexual life but especially anything having to do with same-sex desire or relationships; and he quotes and references an amazing array of arcane archival as well as better known historical sources in support of his contentions.

Kramer's perspective is occasionally spelled out editorially, as in the following passages:

But [gay gathering places] were there. From the beginning of time, they were there. From the beginning of time, of people-in-groups, of people-in-crowds, there are such places. Why, oh why, has it been impossible for us to accept such an obvious fact? That there is so little record of them is a testament to what must have been a nonstop effort bordering on the superhuman to eradicate all traces of their existence on the part of city fathers, and of course historians, and sadly, no doubt on the part of [gay people] themselves. No town, or family or [gay person], wishes such information to be known...There is little we know that was not done then, determined though so many historians are to deny this. It is not much different today but for the numbers.

Likewise editorially, Kramer's legendary exasperation, in this case with social constructionism and historians, is spelled out by one of the more potty-mouthed alter-egos: "History knows dipshit about ratshit...Modern history is a fairy tale told by idiots." In The American People, incidentally, the word shit doubtless breaks all records for appearances on a single page and in aggregate for any novel ever written.

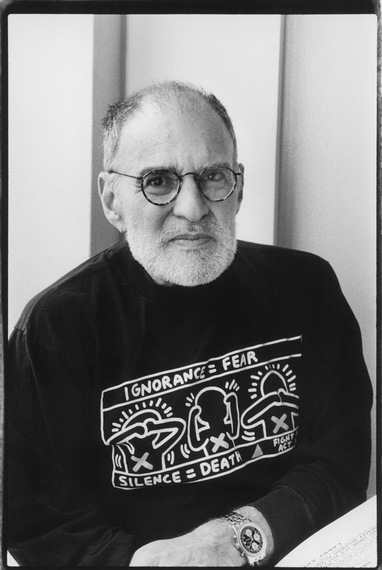

That's Larry Kramer in his characteristic anger. "Let me say before I go any further that I forgive nobody," observes Samuel Beckett in the last of the 12 epigraphs Kramer has chosen to quote in introduction to The American People. As you might anticipate from familiarity with Kramer and his legendary capacity for outrage, and considering the scope of his endeavor, it's not surprising that there's enough rage in The American People to fuel a world war. And as it always has, Kramer's anger at various archvillains can betray a sadistic pleasure in their vilification, in assassinating their personas, in exacting revenge, even in scapegoating them. If only Reagan et al had spearheaded a public health effort comparable to today's containment of ebola, Kramer's narrative suggests, the plague could have been prevented. Kramer wants to make an even stronger case than in the heyday of ACT UP for Reagan ("Peter Reuster") being every bit as culpable, as evil, as Hitler.

The American People is especially notable in looking in depth at historical homophobia and anti-Semitism, individually and together throughout the greater period of WW2. Kramer of course has been outspoken about homophobia in our lives and times and it's thrilling to see him wax so ardently and intelligently about historical anti-Semitism and its entwinements with historical homophobia. If ever there were a supreme proponent of the ACT UP slogan Silence = Death, it's Larry Kramer. It therefore seems incongruous that Kramer has remained so silent about contemporary anti-Semitism. An unfair allegation, perhaps, in light of the forthcoming Volume 2 of The American People, which will cover the period from the 1950's on, but it's one that has come up before -- e.g., with regard to the New Yorker profile on Larry from 2002, in which neither 9/11 nor anti-Semitism is mentioned, as well as in my Larry Kramer anthology. The American People does make reference to a homosexual in Truman's administration who commits suicide because of the gathering storm of Hoover's homophobia. "Jimmy" was against the establishment of Israel because he "foresaw that it would cause nothing but warfare in the Middle East forever." Even though it's the only such reference in the book, one can't help but wonder if Kramer thinks, like Jimmy, that the greater arc of today's anti-Semitism and Islamist extremism is because of Israel.

In The American People Kramer tells the story of several generations of Washington Jews, the Masturbovs, stand-ins for his own family, but with extraordinary twists. The sissy-hating, abusive father Philip turns out to be gay, working for an American firm that enables Hollywood to continue to do business with the Nazis. In the midst of an affair with a middle man in Germany, Philip travels back and forth there. Eventually, David, one of his twin sons, is detained by Nazi doctors, cohorts of Dr. Mengele, who is also represented as sometimes queer and otherwise sexual and whose fiendish experiments on children and especially twins are narrated in excrutiating detail.

The good news: David returns to America alive. The bad news: this "liberation" is actually a transfer from Dr. Mengele's medical concentration camp unit in Germany to its partner camp in Idaho, where the same and worse medical experiments to cure homosexuality and effeminacy are carried out. Which turns out to be just two subunits of what is in fact a worldwide gulag -- in Russia and Japan as well as everywhere else -- of human guinea pigs designated for testing of the newest and biggest front of war: CBW or chemical biological warfare, aka germ warfare.

HBO's new documentary by Jean Carlomusto about Larry Kramer, to be broadcast during Gay Pride in June, is called Larry Kramer in Love and Anger. And indeed and never moreso than in The American People, bound up with all the anger at so much evil and injustice is Kramer's characteristic compassion, concern, caring and love, of all of humanity, actually, but especially of the weak, meek, defenseless and victimized, and especially of gay people.

Kramer analyzes a massacre of young men that took place in the environs of Jamestown during the earliest period of settlement and speculates that those who were murdered were gay. What must it have been like for gay people to have had no context for understanding themselves, to not know what to do with themselves or where or how or with whom to be, to have had no sense of place for themselves, to be living with the cognitive dissonance that what is deepest in their hearts and souls, or even just circumstantially relieving, is "wrong," "evil," "sick," condemned and forbidden by society? The gentleness and pathos with which Kramer imagines the hardships of these early LGBT pioneers who didn't have the resources to better realize that that's who and what they were, is overwhelming.

But soon matched by his recounting of the excesses and losses of the American Civil War. Kramer's passage (I'm not sure what else to call these chapterettes),"The Civil War" will invite comparison to the testimony of Walt Whitman, the most famous gay witness to this history and who Kramer quotes at length and in homage. The American People overflows with accounts of the grueling hardships of the lives of all young people but especially LGBT people -- of the desperation of gay men and lesbians who needed to pass just to survive; of their mind-bogglingly courageous efforts to affirm themselves and their kind, often with the opposition of their own kind; of their inevitable murder by growing and peculiarly American brigades and lone warriors of hate. Search for my Heart," The American People is aptly subtitled and concludes, quoting Baudelaire: "Search for my heart no longer, the beasts have eaten it." But finding Kramer's abnormally big heart in The American People is as easy as being engaged by Kramer's volcanic anger and mighty voice. It's right there, front and center, in every word, each one lovingly and carefully selected, on every page. Whatever the disappointments and reckonings with history, with his own life, with the simple romantic love that he believed in so deeply as an innocent young gay man, with lovers, with gay life, with friends, with family, with America, there is one surpassing love and heart's home that has remained as unwaveringly faithful to Larry Kramer as he to it -- his muse.

Following his leadership of ACT UP, Kramer moved on to establish a LGBT studies program, the Larry Kramer Initiative, at his alma mater Yale. Varyingly under the sway of stodgy traditionalists and social constructionists, the powers that be at Yale ("Yaddah" in The American People), seemed to be doing everything they could to undermine and relegate the LKI, which they believed, at best, belonged under the auspices of gender studies and/or that it wasn't an otherwise fully legitimate, justifiable enterprise. Clearly, The American People aims to upend the historians, scholars and custodians of traditions Kramer did battle with at Yale within wider spheres of academe. To say that Kramer believes that LGBT people have been deprived of our history with the collusion of academics, intellectuals and historians, gay as well as mainstream, would be the biggest understatement you could make about Larry Kramer and The American People. Not surprisingly, the muckraking Kramer has done about the origins and pillars of "Yaddah" and "New Godding" paints a very different picture than that which this otherwise most esteemed institution of American learning and American presidents would want the world to see. The Yale that is dissected in The American People is the alma matter of genteel homophobes like William F. Buckley and George W. Bush and was the home of the leading literary critic Newton Arvin, who committed suicide after being publicly indicted for "lewdness."

A launching pad for Kramer in writing his epic tome were Ronald Reagan's commonplace references to "the American people," which Kramer correctly appreciated as not including gay people. It is Kramer's agenda not only to make the case for LGBT American history but to make the case for it as something much greater than anything ever imagined by any of us. What Kramer envisions with The American People is nothing less than a complete rewriting of history as we've known it. By now, everyone has heard of the contention that Abraham Lincoln was gay. (For the record, there are comparable claims that Lincoln, who had significant and positive relationships with Jews, was part Jewish.) Kramer goes much much further, alleging that not only Lincoln but Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Presidents Jackson, Pierce, Buchanan and perhaps other presidents, as well as Lewis and Clarke, de Tocqueville, LaFayette, Burr, John Wilkes Booth, Samuel Clemens, George Custer, Oliver Wendell Holmes, visitors to America such as Sigmund Freud and his alleged lover Wilhelm Fliess, virtually every actor in Hollywood past and present, including one who became president, and so many others, were gay or did it with men at some point.

As part of its commemorations of Black History Month, the New York Times published an editorial about the extent and details of Washington's ownership of slaves, Why, in the harsh light of what we now realize about our founding father's willingness to exploit what he otherwise realized was the morally and ethically untenable institution of slavery, is it so inconceivable that this military man, in a passionless and childless marriage, might have been gay? The point of course is not that being gay has some kind of connection to or equivalency with endorsing slavery, but that Washington's relationships to slavery, like questions of his sexuality, are aspects of the life of Washington that people have relegated and don't seem to want to know much about. When recently asked if he were really so sure that Washington was gay, Kramer rejoindered: "Are you really so sure he wasn't?"

Not too surprisingly after the passages on Washington, Hamilton, Lincoln and Booth, Kramer seems eager to buy into the notion, on the basis of well-known circumstantial evidence, that Hitler was homosexual, notwithstanding that this exemplar of faggification of the enemy has never been made to stick. Even so, in light of its myriad examples of how aggressively homosexuality and any evidence of it was covered up, The American People is seductive in asking us to look yet again at the question of Hitler and homosexuality, just as it asks us to do with virtually every other known public figure of the past.

The American People is mesmerizing. Despite it's Gargantuan length and sprawl, it is very readable, not only because Larry Kramer's writing is so accessible, so human, so personal, so caring, so heartfelt, so courageous and so resonant, but because of the way the book is constructed, as a series of mostly very short, readable segments. It's possible to sit down and read a vignette or chapterette for a few minutes. It doesn't demand that you read it for hours on end, though such a gifted writer is Larry Kramer that that's what you will inevitably want to do, especially since, as with most great novels, the momentum builds.

Volume 1 of The American People is 777 pages. Volume II is expected to be similarly voluminous. The two volumes together will probably be about the same length as War and Peace. In an introduction Kramer indicates plans to independently publish some 2000 additional pages beyond Volume 2. It seems almost preconceived that it cannot ever conclude as you might expect of a novel, drawing all the disparate strains together conclusively or even meaningfully. While there can't be any question that Kramer overshoots with so much fire -- e.g., Lincoln's assassination is reinterpreted as a gay love triangle with Booth, gone south, that Clemens was gay and that his "Huck and Nigger Jim were lovers" -- the greater truth Kramer so persistently makes the case for seems credible: that the histories of the American people that have come down to us, even from many contemporary historians, are so myopic, naive, reticent and constipated about the impact of sexuality and especially homosexuality and bisexuality in historical life and relationships and events, that nothing less than the entirety of this history needs to be reexamined and rewritten. For this reason alone, The American People is likely to find its place among the notable works of the Western canon.

How well does The American People work as a novel? The answer to that question must await volume 2, due out next year. Meanwhile, how well does what is there in volume 1 work, hold together? In his career as a writer, Kramer has sometimes misfired badly, or seemed to have, even by his own estimation -- e.g., in the screenplay he did for the musical remake of the Hollywood classic, Lost Horizon, and with his play, Just Say No. But such are Kramer's powers of insight and his gifts for prophecy as well as his skills as a writer that even these works will have to be re-explored and mined for riches by future scholars, critics and historians. Like his activism, Kramer's writing has never been known for its tidiness or prettiness, for its surfaces or for decorum, although his writing is so confident and fluid that it seems to have, in league with the greatest writers, its own lilt, language and cadences as well as a signature blend of gay, Jewish and mordant humors. As a novel, it's likely that The American People will come under fire for a lot of violations of various rules of fine writing. Perhaps a better question than how well it all works and holds together might be does The American People help us to see and question our own lives and times and histories to an extent and with a success that can be claimed by few other writers? While it may be too soon to know exactly what places The American People will eventually find for itself, one thing's for sure. The American People, which one of our greatest leaders, champions, voices, thinkers, sages, prophets and writers has labored on for 40 years, is here to stay. Eloquent, powerful, epochal, defiant, relentlessly in your face and tough as shit on everyone and everything, this astounding novel is no more likely to accept the silent treatment or any other kind of rejection than Kramer himself ever would.

_____

Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., wrote the first published press reports on AIDS and is a co-founder, with Kramer, of Gay Men's Health Crisis. He is the author/editor of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer and Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: Being Gay and Jewish in America.