Twenty-two year old Eunice Gonzalez-Sierra, is immersed in the hopeful yet anxious process recent grads experience when looking for their first professional job. Confident that she will land a job at one of the local law firms in Santa Maria, California, she takes to her Tumblr blog and sends messages of support to others who are steeped in job applications and checking their email constantly for any replies. But Eunice is no newbie at managing pressure brought on by high expectations and a Mexican work ethic.

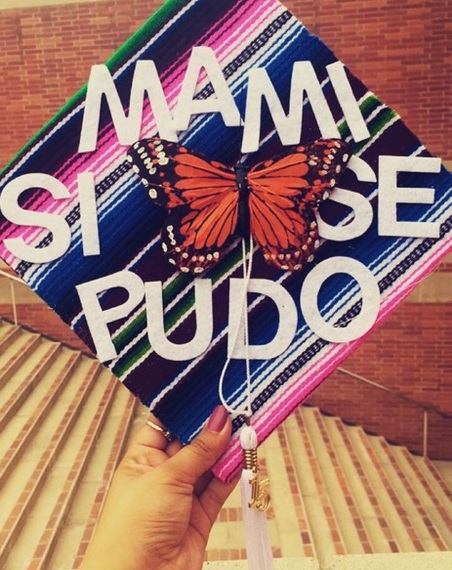

This work ethic led her to cross the stage and receive a bachelor's degree in Chicana/a Studies and a double minor in Labor and Gender Studies from UCLA in June. She is the first college graduate in her family. Eunice was also co-chair of UCLA's 42nd RAZA Graduation with the largest participation of graduates since its inception in 1972, where students' culture, language, and family are an integral part of the celebration, allowing for multilingual and multicultural experience. Participation is open to all students.

As she spoke to her peers at the RAZA Graduation she congratulated them in Spanish and English about their achievements. But Eunice was quick to point out that their success was only due to the hard work of the people that gave them the strength to keep going and graduate.

She made it clear, that the coveted college diploma, that has meant access to a different future from that of their parents for thousands of immigrants before her, was not just a prize earned by the individual but a communal achievement made possible by fathers, mothers, and extended family members who willingly faced physical danger and the brunt of social and institutional racism in hopes that the youngest among them could carve a different life for themselves.

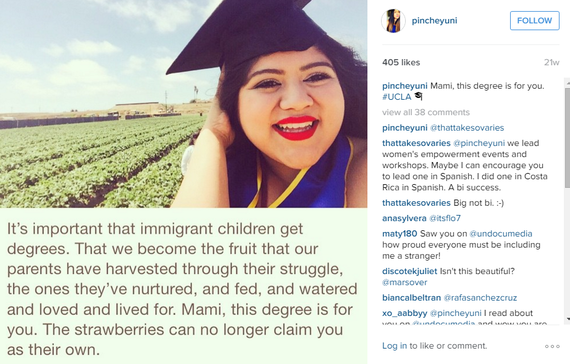

Eunice remembers her parents' life over the last twenty-two years and honors her mother for laboring in the strawberry fields since she was born, so that she could sit in a classroom. She gives her credit for making her the woman she is today and also honors her father, who worked alongside her mother in the fields, for making her a true chingona, a badass.

Eunice with her parents at her post-grad photo shoot in the strawberry fields they work in. Photo: Courtesy of Jorge Mata Flores

Eunice with her parents at her post-grad photo shoot in the strawberry fields they work in. Photo: Courtesy of Jorge Mata Flores

They crossed the border from Mexico into the United States twenty-two years ago. Similar to the 1,713,251 European immigrants that crossed the Atlantic Ocean between 1841-1850, according to the Harvard Open Collections Program on Immigration from 1789 to 1930, and to the millions more that continued to arrive seeking access to opportunity.

For Eunice's parents access came in the form of the ability to gain work immediately picking strawberries in what became California's billion dollar strawberry industry according to the USDA statistics service. This meant getting up at five in the morning to go to a field to carrying two empty boxes across a field that weigh about eleven pounds each when filled.

The boxes are then carried back and checked in where someone keeps a tally on the boxes each worker fills to pay them at the end of the day. They then pick up two more empty boxes and cross the field again, with temperatures ranging from the 60's-80's in one day for the next 12-16 hours. In Eunice's parents case they did this for twenty-two years.

As Eunice recalls her parents' journey with me, she is still in awe that for living such a physically demanding and harsh life, she has never heard her parents complaint. Her dad's greatest wish was to see the day he could get a driver's license and pay taxes.

They stay in the shadows, as most undocumented workers must , working from sun up to sun down for minimal pay, to ensure that the rest of America can have strawberry short cake, strawberry ice cream, strawberries in their cereal.

But it also meant steady work and access to elementary, middle, and high school education for their daughters. And for Eunice, one of five, an opportunity to go to college.

However, as many college students know making it into college is not enough to keep you there. There is a vast social and academic system that students must navigate and resources they need to tap into to manage the work load and community expectations.

For students whose language, culture, and economic means is vastly at odds with the majority of the students, figuring out the knowhow of how college works is layered in a series of foreign and sometimes, what can appear to be, invisible rules.

Maylei Blackwell, Professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies and Women's Studies at UCLA and one of Eunice's former professors, whose research focuses on indigenous migration, discusses what it means to have a degree when you are a child of indigenous field laborers.

Students like Eunice are super heroes. They really have come such a long way, sometimes, with a lot of the support of their parents who have such important educational aspirations for their children and really push them to strive. [They] have a lot of discipline themselves but don't have the cultural capital to move their children along. Often times they don't speak Spanish or English but an indigenous language making access that much harder. It is kind of a miracle. It shouldn't be but it is. It represents their heart and dream and the perseverance and courage of their families and of themselves.

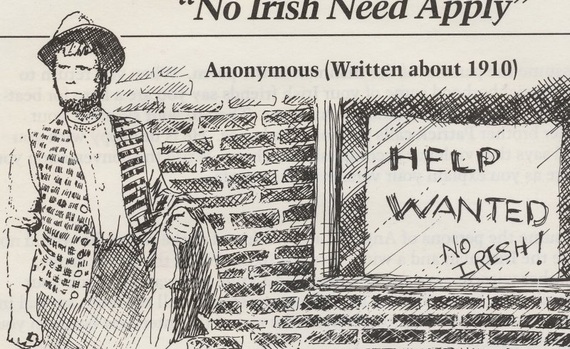

It is a dream not specific to Mexican immigrants but to immigrants worldwide as far back as human need has propelled groups of people in search for stability. Each immigrant wave has received a different reception often depending on who is coming, who is receiving, and the reason behind the move. The indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere were not necessarily excited to have their land taken, people massacred, and food sources taken by Europeans seeking a better life.

In the 1840s and 50s Germany's agricultural problems, Ireland's infamous Potato Famine, and general social upheaval due to industrialization led to higher rates of European immigration to America. Neither group was openly welcome by earlier waves of European immigrants already established in the U.S.

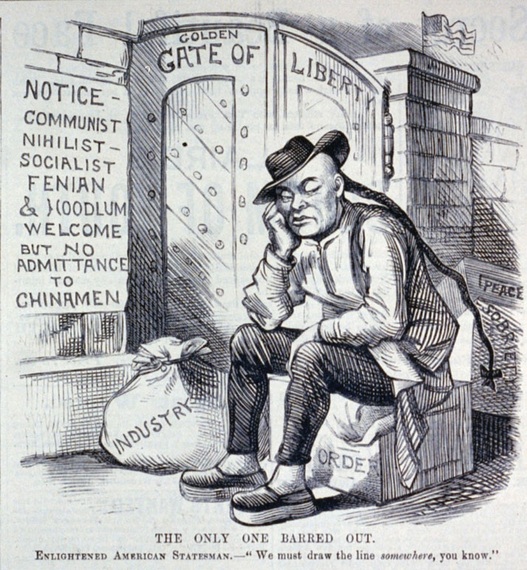

The Gold Rush led to Chinese immigration which was then fiercely blocked for decades about twenty years later with the exception of labor to build the railroads.

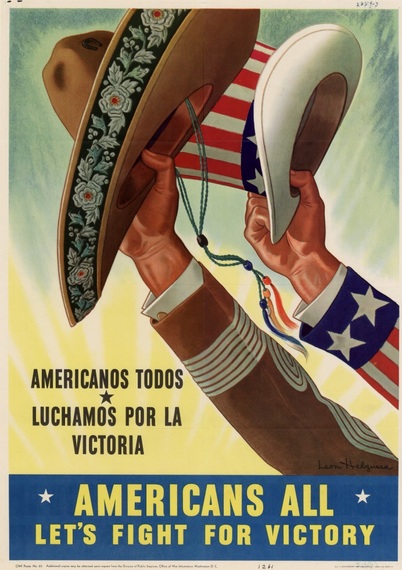

The Bracero Program was created, a guest worker program for able Mexicans, when the United States needed quick and ready labor to fill U.S. labor shortages in low paying agricultural jobs during WWII.

Courtesy of Helguera, Leon. Americans all, let's fight for victory : Americanos todos, luchamos por la victoria.. Washington D.C.. UNT Digital Library.

Courtesy of Helguera, Leon. Americans all, let's fight for victory : Americanos todos, luchamos por la victoria.. Washington D.C.. UNT Digital Library.

Mexico's economic crisis of the 80's and 90's led to waves of immigration to the U.S. As of 2013 Oaxaca, where Eunice's parents are from, is one of the poorest states in Mexico where over 50% of the population live on $62 a month. But jobs are not the greatest obstacles- access to water and safe childbirth are at the top. According to the World Bank in 2012, 78.9 of women out of 100,000 died of child birth and only 69% of the population had running water.

Today immigrants, in particular Mexican immigrants, are once again bearing the brunt of fear based thinking. Cries of "these people are taking our jobs" or "these people are criminals" are still used as anti-immigration arguments.

However, one of the leading organizations for immigration reform, which has existed since the eighties and serves as a model for immigration advocacy for undocumented workers is The Emerald Isle Immigration Center (EIIC).) It lobbies for the Irish Immigration Reform Movement. In 2007 there were at least 50,000 undocumented Irish 30,000 in NYC area alone as reported by the Los Angeles Times.

A crossing of undocumented people supported by Hilary Clinton. Support that their Mexican counterpart has never had.

In response to this age old scapegoating, the United Farm Workers created the Take Our Jobs Campaign in 2010 in an effort to "give back" the jobs they had "stolen" to American born citizens. The UFW offered work to anyone who was willing to work in the fields. Out of 8,600 who expressed an interest in seeking employment as farm workers, only eleven people actually took a job in agriculture.

Gabriel Thompson was one of these people. He wrote the memoir, Working in the Shadows: A Year of Doing the Jobs (Most) Americans Won't Do. Listen to the NPR interview with him and United Farm Workers president, Arturo Rodriguez, about the Take Our Jobs Campaign and Thompson's experience in the fields.

Three years later none of the people continued as farm laborers. Watch this video to see the update.

This has been a civil rights movement, says Professor Blackwell, for many people in the shadows they don't understand the prejudice. The way the media has distorted the issues and focused on the hysteria not on the actual global conditions that have created the conditions of migration. The U.S. has played a lot on those conditions so it isn't by accident that people embark here. We should stop kidding ourselves that the U.S. economy doesn't need these migrants. The response of the U.S. is a breeding ground for racism and hatred rather than one of understanding of global conditions.

The reality for Americans is that we are so far removed from the source of our food production and general goods and services that we will literally bite the hand that feeds us. Grocery stores are packed with produce year round, shelves are stocked with canned goods, refrigerators can't seem to get big enough, summer picnics never miss a watermelon, Napa Valley has not seen a decline in wine tours, but yet many people are still in denial of what it takes to get that food and drink there.

Imagine not having to go to the gym or go on a diet because your job was so physically taxing you never consume more calories than you spend, actually you can't even eat what you pick. Then try living on less than minimum wage, without health insurance or benefits, and having the rain determine your work for the season. Rain can often ruin an entire crop of strawberries. Food many times picked by children and pregnant mothers, as child labor laws for agricultural work are different.

Immigrants are propelled by the vision for a future that often becomes stagnant from wars; corrupt governments; violence; racial, religious, and ethnic intolerance; and back room deals that favor the elite and leave the masses to bear the brunt.

Opportunity wrought by hard labor and fueled by the collective desire of masses of people willing to face the unknown for the ability to simply survive, to feed themselves, clothe themselves, have shelter, clean water, and maybe something different for their children. Just look at Cesar Montelongo's experience as an MD-PHD student.

Let us try to remember this as we celebrate in a few weeks the very crossing that defines American agriculture, the feast of the first harvest,Thanksgiving. A feast to celebrate when Pilgrims, the first undocumented immigrants to America, were fed by the kindness of Native Americans, from brown hands to white hands, only to be massacred in return.

At the end of Eunice's speech she spoke directly to the future of this country- her peers, younger siblings, and cousins, cheering from the stands, "To you, we are waiting to go to your graduations, to see your diplomas because, "¡Sí se pudo! ¡Sí se puede! y ¡Sí se va seguir pudiendo!" "It was done! It can be done! and It will continue to be done!" A thunder of applause broke out.

An anthem for an immigrant nation where crossing borders and cultures out of necessity, in hopes of greater opportunities, are as American as apple pie (which, by the way, was brought by British and Dutch immigrants.)

Photo: Courtesy of Eunice Gonzalez-Sierra

Photo: Courtesy of Eunice Gonzalez-Sierra Photo: Courtesy of Eunize Gonzalez-Sierra

Photo: Courtesy of Eunize Gonzalez-Sierra Photo: Courtesy of Eunice Gonzalez-Sierra.

Photo: Courtesy of Eunice Gonzalez-Sierra. Photo: Courtesy of Eunice Gonzalez-Sierra.

Photo: Courtesy of Eunice Gonzalez-Sierra. Courtesy of Creative Commons

Courtesy of Creative Commons

Photo by: irishvoices.blogspot.com

Photo by: irishvoices.blogspot.com Field workers flanked four by four on each side of a rigged school bus, clearing a watermelon field by throwing watermelons to each other and then into the bus. August 2015, Salisbury, MD. Photo: Courtesy of Catalina Sofia Dansberger Duque

Field workers flanked four by four on each side of a rigged school bus, clearing a watermelon field by throwing watermelons to each other and then into the bus. August 2015, Salisbury, MD. Photo: Courtesy of Catalina Sofia Dansberger Duque