Many years ago, when I was a special education teacher, I had a summer job at a residential school for emotionally disturbed children. The school happened to be located in a former tuberculosis sanitarium. Later, I heard from other teachers elsewhere about having worked in schools in one-time sanitaria as well.

How did it come about, one might ask, that tuberculosis sanitaria across the country became available for use as schools? The answer is that researchers cured the disease. The sanitaria were no longer needed for their original purpose, so they were turned into schools.

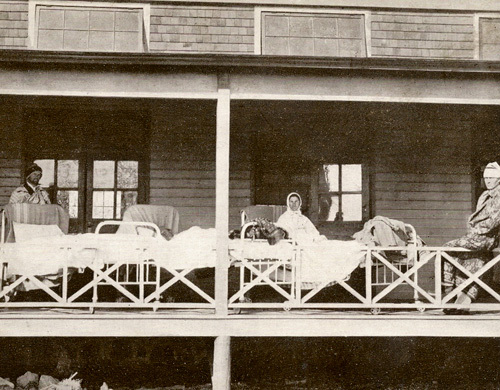

One feature of the former sanitaria is that they all had morgues. We used ours to store curriculum materials, because it had very sturdy and useful sliding horizontal cabinets. This arrangement led to a certain amount of macabre humor, but the morgue reminded us that what the sanitaria had once done was deadly serious indeed.

I was recalling my summer in the sanitarium after reading about the latest developments in the reauthorization of ESEA. Both the House and the Senate have now passed bills that eliminate the Investing in Innovation (i3) program and cut funding for the Institute of Education Sciences. In their place, the bills have a lot of language about state and local control, and about identifying and publicizing individual schools that are doing a particularly good job so their good works can help inspire and influence other schools. None of this would bother me if the legislation contained a clear commitment to rigorous research, development, and dissemination, but this may or may not be the case.

The Senate bill, which passed with bipartisan support last week, does authorize an evidence-based innovation fund. Modeled on the successful Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, which funds innovation and evaluation in 11 different government agencies, this initiative would provide flexible funding for a broad range of field-driven projects and allow schools, districts, non-profits, and small businesses to develop and grow innovative programs to improve student achievement. Grants would be awarded using a tiered evidence framework based on an applicant's proven effectiveness. The provision was initially offered and accepted as a bipartisan amendment during the Senate HELP Committee markup of its bill. However, the House bill has no comparable provision, and I have to wonder if the Senate provision will survive the grueling conference process and make it into the final bill.

Try to imagine what would have happened if tuberculosis research had been treated the way education research has been treated in the House version of the ESEA reauthorization bill. Individual sanitaria with lower death rates might be recognized. States and localities might try out ideas to make the sanitaria more effective, but few if any states or localities would be large enough to do the necessary sustained R & D. "Best practices" would be constrained by the current system, so they might involve better ways for sanitarium staff to do exercises with patients, for example, rather than experimenting with medications or other treatments. The disease would never have been cured. The morgues would still be used for unfortunate patients, not for curriculum materials.

The U.S. spends hundreds of billions of dollars every year on education. What student, parent, teacher, administrator, or policy maker does not want those billions used to make as much of a difference as possible? The pursuit of knowledge about how to improve educational outcomes is obviously important, but it is rarely very high on anyone's priority list.

Fortunately, medicine and other fields long ago decided that research was in the national interest, and that investments in research were the most reliable way forward in improving important outcomes. In medicine, the choice is stark: either the evidence prevails or the morgue does. Yet in education, anyone with eyes to see knows what happens when children fail to learn. Most of the children who cannot read end up unemployed. Many end up in prison, and all too many in the morgue. We know enough now to be able to say that the great majority of reading failure, for example, is preventable. Yet we choose not to prevent it. What does this say about us as a people, as a society, as a political system?

I hope our leaders in Congress approve the Senate language on evidence, or something similar, and reinstate and fund programs that have the greatest promise in identifying and disseminating effective approaches to key problems. The lives of a generation of vulnerable children depend on their wisdom and courage at this critical juncture.