This Post appeared on the blog ScreenCraft. ScreenCraft is dedicated to helping screenwriters and filmmakers succeed through educational events, screenwriting competitions and the annual ScreenCraft Screenwriting Fellowship program, connecting screenwriters with agents, managers and Hollywood producers. Follow ScreenCraft on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube.

In 1965 I was working for an animation studio in Borehamwood, England making little animation projects for the BBC and the military. I saw an article in the London Sunday Times that my favorite director, Stanley Kubrick, was going to make a science fiction film at the MGM studio up the street. The name of the film was 2001: A Space Odyssey.

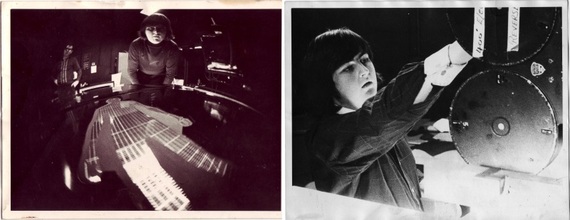

Shortly after, the stars really lined up for me. VFX pioneer Doug Trumbull came to our company head hunting for animation artists to work on the film. Back in those days if you had a steady job with a good company you certainly weren't interested in taking a freelance job for six month or so. But I was foot-loose and fancy-free and interviewed for the job -- and got it.

Little did I know that the job would last for two and a half years -- the longest gainful employment of my life in the business -- and also be the most influential experience of my career. Little did I know that I would be sitting in dailies with Stanley Kubrick critiquing my work for the next few years. I think if someone told me I had to do this now, I would have a nervous breakdown. But I was nineteen years old and didn't know any better.

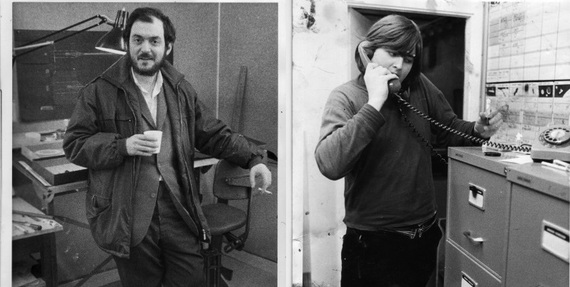

So, what was Stanley Kubrick like?

My experience with the man was that he was a deeply caring, gentle, and empathetic human being with a great sense of humor. But that was the man. As a filmmaker, he was intensely driven and ruthless on the journey to create his vision. Once when I was sick for a couple of days, he rang me up at home and threatened to send an ambulance to my house and bring me in on a stretcher to shoot animation.

He also had some idiosyncrasies that made him very similar to his character of Gen. Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove. He would only drink bottled water -- pretty unheard of for England in the 60s. He liked to have his pockets completely empty so he left his keys in the car and would bum cigarettes off the rest of us. He loved that in England at the time he didn't have to carry ID. He had a private pilot's license but would never fly on a commercial airline. If he traveled anywhere it was by boat and train -- this why the "Dawn of Man Sequence" was shot onstage with front projection, as it would have taken Stanley too long to travel to Africa. He had a sign in his office warning us all, "No Half-Baked Ideas."

Dailies and Discipline

I was hired as an animation artist but when Stanley found out I could shoot animation as well, he doubled my salary and my work-load became two fold. I would create animation artwork and then shoot it.

In dailies, Stanley would sit out front very near the screen in a chair between the screen and the front row of seats. He had what was known as a "beer-mug" in his hands, which did look somewhat like a beer-mug but was actually a Selsyn motor. Selsyns were twin motors which were synchronized to each other. The twin to the one Stanley held was hooked up to the focus control on the projector. Stanley had gotten tired of calling on the intercom for the projectionist to "run through focus," so he could see how sharp the image was. Instead he would crank the handle of the beer-mug back and forth so he was in total control of the image.

I would have a one-on-one meeting with Stanley at the front gate every morning, which in retrospect I should have been rather embarrassed about. As an irresponsible teenager, I was always late. So late that Stanley would be pulling into the studio in his Rolls Royce at the same time I pulled in in my mini-van. Far from being embarrassed, I would just smile and say "good morning" and he would return the greeting in a very friendly manner instead of berating me for being late. I have to say that my days usually consisted of coming in late, taking a long morning tea-break, a long lunch at the commissary, and then finally getting down to work after lunch. But when six o'clock rolled around I had shot more footage than any of the other cameraman. So somehow I seemed immune to being disciplined.

However, I did get fired at one point. There were several other animation cameramen hired and I was relegated to the night shift. The new cameramen were journeymen technicians and I was just a young kid, so they often tried to torpedo me at dailies. Being on nights, I did not attend dailies to defend my work and was fired. I was pretty depressed for a week or so -- until I got the call to come back to work. I agreed on the condition that they doubled my salary. I guess I had a lot of nerve for a young kid! I don't think they doubled it but it was a hefty raise.

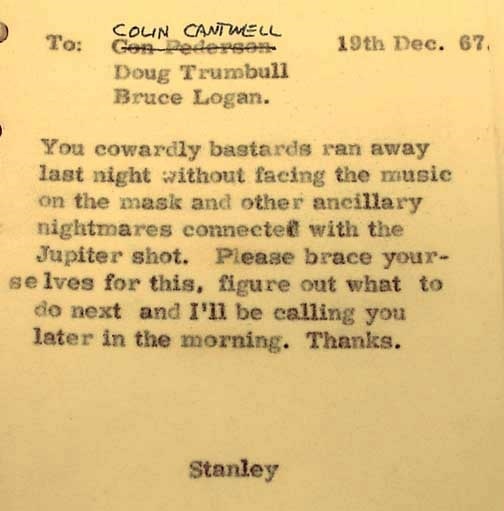

You Cowardly Bastards!

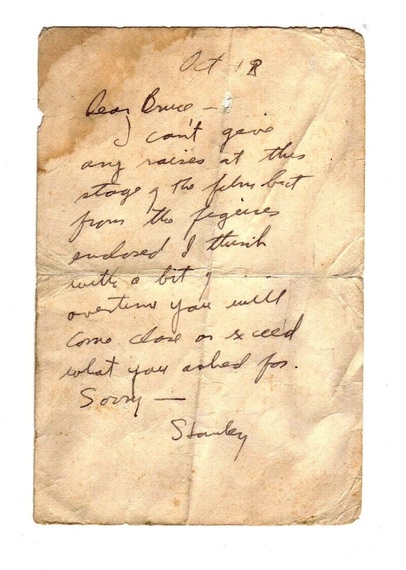

I asked for one more raise before the film was over. Here's Stanley's response:

I guess I pushed it -- and him -- as far as I could. Here's another memo that gives you a feeling for Stanley's directorial style:

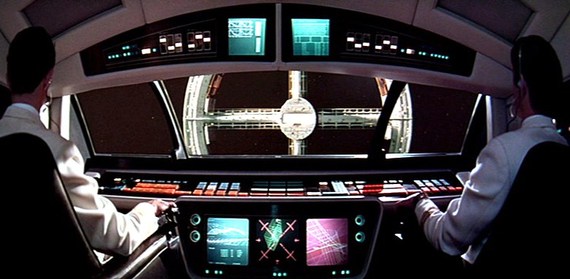

My last job on the movie was to shoot the opening scene of the film with the main title. Stanley was a stickler for quality and didn't want any foreign country having a duplicate negative for the title in their language. So I had to shoot the sequence seven times in the various different languages.

The shot was 1440 frames long and it was five passes -- the sun, the stars, the moon, the earth, and the title. It took me a day for each shot and was a fitting end to my work on the movie.

Before Stanley left to color time 2001 in Culver City, I asked him how he got the ideas for his next projects. He said it was a good question and went right to the heart of his amazing career. He had no answer for me.

This blog was originally posted on zacuto.com. Zacuto creates production grade, filmmaking camera accessories designed by filmmakers for filmmakers. Zacuto's blog is written by a wide variety of filmmakers and includes How To articles, production diaries, sneak peeks at new cameras, and more. Learn more about Zacuto by following them on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Vimeo.

Bruce Logan, ASC was born in London. His love of imagery started when he was hired by Stanley Kubrick to work under Douglas Trumbull on 2001: A Space Odyssey. He came to California in 1968 and worked as a DP on over a dozen films, including: Tron, Star Trek, Airplane, Firefox, High Road to China, The Incredible Shrinking Woman, I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, Big Bad Mama, and Jackson County Jail. He did visual photography for most of these films as well. He has shot commercial films for most of the major companies: Pepsi, GE, Visa, Chevrolet, Pontiac, DuPont, Contac, Sprint, Amtrak, Suzuki, Sunlight, and Armstrong. And he has applied his talents to making music videos for such high profile performers as Prince, Madonna, Rod Stewart, Aerosmith, Glenn Frey, The Go-Gos, Karyn White, Tevin Campbell, Hank Williams, Jr., and Michael Cooper. See Bruce's full bio here.

More from ScreenCraft: