"Nothing is precious except that part of you which is in other people, and that part of others which is in you. Up there, on high, everything is one." -- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

At the root of the culture wars lies a fundamental dichotomy in worldviews. Which is more essential to humanity: the individual or the collective?

The philosophy of Ayn Rand, as articulated in her novels The Fountainhead (1943) and Atlas Shrugged (1957), undergirds one extreme of the cultural divide. Rand, a Russian Jew who immigrated to the U.S. in 1926, espoused a libertarian philosophy that leaves the individual unencumbered to pursue self-interest, enlightened or otherwise. Rand promoted the "virtue of selfishness" and reviled altruism, elevated reason and denigrated intuition, idolized laissez-faire capitalism and condemned all forms of religion and moral persuasion.

Rand, who portrayed the poor as "leeches" on the rich, is the patron saint of ultra-libertarians such as Ron and Rand Paul. Paradoxically, some Christian conservatives -- Paul Ryan comes to mind -- also idolize Rand, despite her militant atheism and "utter lack of charity or empathy."

Carried to its logical conclusion, the extreme individualism and "rational egoism" promoted by Rand lead to radical independence -- and ultimately isolation -- from other beings. In many religious traditions, hell is just such a state.

The other extreme of the cultural divide was fully actualized in the system Rand fled: Soviet communism. The Cold-War Soviet state callously and routinely sacrificed individuals to the cogs of the collective agricultural and industrial machines. The individual served as a mere drone in a hive. Drones were expendable so long as the hive survived.

Both extremes reveal the truth of a Cold-War-era joke: "What is the difference between capitalism and communism?" Answer: "With capitalism, man exploits man. With communism, it's the other way round."

Extreme collectivism undermines creativity and initiative, ultimately crushing the souls of individuals. It is no coincidence that alcoholism was epidemic in the former U.S.S.R. Extreme individualism, on the other hand, grants license for individuals to destroy the commons -- soil, air, water, and climate -- on which we all depend. It is also no coincidence that the U.S., champion of unbridled capitalism and unfettered globalization, has lead the way in the destruction of the commons.

There is a third way.

The renown French paleontologist, Jesuit priest, and mystic Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) articulated many novel and illuminating concepts: cosmogenesis, complexity-consciousness, the noosphere, and -- pertinent to this discussion -- union differentiates.

The latter theme permeates his great work The Human Phenomenon (1955). It originates in Teilhard's observations that all components of the universe -- whether subatomic particles, atoms, cells, or biological organisms -- unite with other such entities to create more complex structures. The tendency toward union is innate in matter.

The American philosopher Ken Wilber expresses a similar notion through the concept of holons. Wilbur describes a holon as an entity with a dual purpose: it is at once an autonomous individual and part of a greater whole. Holons exist in nested hierarchies: quarks, atoms, molecules, cells, organisms, societies, worlds, and so on. Teilhard and Wilbur concur that, far from losing its identity in union, an individual (or holon) becomes more truly itself by contributing to a greater whole (holon). "Fuller being is closer union," wrote Teilhard. And individuals without community, he painted in words poetic, are but a "cluster of sparks extinguished ... in darkness."

Still, the apparent paradox of Teilhard's axiom "union differentiates" makes it intellectually challenging: (integration) union and differentiation are opposites, mathematically and spiritually. The concept is best apprehended through experience rather than intellect. My ah-ha moment came in 1970.

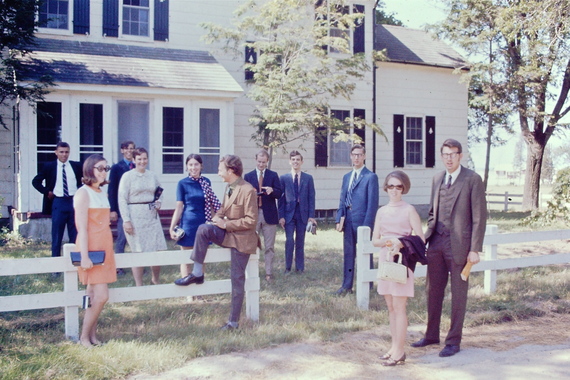

Following graduation from college, I joined a "summer missions" project under the auspices of a mainstream protestant denomination. Our co-ed group consisted of 13 college kids from a wide swath of America, and a 20-something married couple, our leaders.

The 15 of us lived under one roof, in the ramshackle clubhouse of an abandoned golf course. Tasks split along gender lines. The guys did church construction: pouring concrete, framing walls, hanging rafters. The women (I wince in retrospect) cooked, washed, and cleaned. The musically inclined, female and male, formed a folk group and ran the "Crossroads," our bi-weekly coffee house for footloose local youth.

Group living was stressful. Conflicts arose over rigid gender roles, perspectives on the Vietnam War; and the difficulty of balancing the competing demands of caring for ourselves and serving the community. The summer could have exploded in our faces, and did for subsequent mission teams.

Our group was fortunate. Mike and Susan, our house-parents, having recently married, had first-hand experience in working through gender-role issues. Moreover, Michael, completing his doctorate in psychology, had trained in counseling. At his insistence, we talked out and eventually sorted through most conflicts.

Although not utopia, the work-camp experience was extraordinarily positive for me, a model of Teilhard's axiom that I would only much latter come to appreciate: union differentiates. Like flowers awakening to the sunshine and showers of spring, individual personalities blossomed. By summer's end, each person filled an essential niche in our communal life. So powerful was this impression that I wrote into the wee hours of our last night, crafting reflections in verse for each and every participant. I remained buoyed by the whole experience months thereafter. Forty-five years later, reflecting on summer 1970 still evokes all kinds of positive feelings.

These musings convince me that the culture wars are pure political theater, intended to distract both sides while foxes raid the henhouse of democratic society. We need healthy communities and we need liberated individuals. The individual thrives only in the rich soil of a healthy collective, and the collective thrives only when its individuals are empowered to exercise their unique gifts.

Teilhard had it right: union differentiates. The best gardeners pay attention to both the plants and the soil.

(The author is indebted to poet and friend Charles Finn for encouragement, insight, and editorial suggestions.)