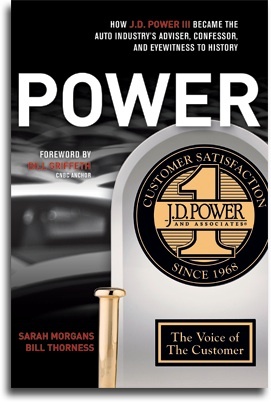

Part One: J.D. Power shares how he started his legendary company, and what we can learn from it.

J.D. Power's name is synonymous with automobile quality, but what you might be surprised to learn is that this man--and his company--has almost single-handedly revolutionized the way Americans think about cars and decide to purchase new ones. At a time when the American automobile industry is changing yet again, J.D., or Dave as he is known, shares his knowledge of market research and the wisdom years of measuring the market has taught him.

J.D. Power, or Dave, the founder of J.D. Power and Associates has spent decades not only building a successful global company, but also revolutionizing how consumers access information about product quality.

Through the retelling of his company's founding, and his tale of entrepreneurship, I came to learn some important lessons in what it takes. I commend Dave for the effect he has made on quality--both in production and marketing.

(Source)

Dave was born in 1931--in the midst of one of our nation's greatest economic catastrophes and one of the lowest birthrates on record. He attended College of the Holy Cross, before joining the Coast Guard during the Korean War. And surprisingly, his story begins on an icebreaker in the Arctic before a stint on Ford's finance staff and trailblazing through the market research field in the 1960s and 1970s.

SM: How did you join the US Coast Guard?

JDP: Rather than being drafted, after I graduated college in March of 1953, I chose to enter the Coast Guard's Officer Candidate School and then was sent to an icebreaker in Boston. We were assigned to missions in the Arctic and Antarctic. In fact, on the trip to the Antarctic we were the furthest south of any icebreaker--or any ship at that time, in the McMurdo Sound. There were a bunch of penguins around. They weren't scared at all. They wouldn't let us touch them, but they hadn't seen human beings before. It gave me the opportunity to see the world and to gain real world experience. On one of the trips to the Arctic, Walt Disney Productions chronicled our trip, in a short film called Men Against the Arctic. It won an Academy Award in 1956. I was watching the sunset as we turned around to head south--just a shadow in the film.

The icebreaker (Source)

SM: What brought you from that icebreaker to the world of marketing?

JDP: The Korean War was over and my time was up. I did not know what I really wanted to do. So, I applied to several graduate schools and planned to figure out my career based on where I was accepted.

I received an acceptance letter from Wharton, stating that they had too many engineers and too many financial-type people going through the MBA program --and that they wanted to add some variety by bringing in people who had traditional liberal arts degrees like me. I liked the way that they appealed to me and immediately accepted. Come to find out, the dean of admissions was also in the Marketing Department and he taught a class on 'market research'. That is when I fell in love this relatively new concept.

SM: What is one of the first times you made a formal analysis in the industry?

JDP: Ford Motor Company recruited at Wharton and I was one of several MBA graduates who was asked to join them in Michigan. They ended up assigning me to the Ford Tractor Division in Birmingham, Michigan, which was not exactly the most prestigious place to go when you think that you are being hired into Ford.

Despite what I thought at the time, the experience in a smaller operating division at Ford actually gave me much broader and deeper understanding for which I am grateful. One of the first projects I had was to audit tractor dealers after a 4-month sales promotion.

I went to one particular dealer on to verify the reported sales of tractor accessories between Ford's records and the dealership's records. I was warned that it was a bit of wild operation. I got there at 8 o'clock in the morning and the dealer turned me over to his bookkeeper.

I started out by asking her to cross check the serial numbers for units sold on Ford's sales list and had to question her about which ones were on the dealership's list, and I started saying, "What about this tractor?" and she couldn't find it in her sales journal. I then asked about the next one on the Ford list and again she could not find it on the dealership's list. After five more like that she got really upset. She burst into tears and said, "I told them he'd get caught! I'm going to quit this job and go back to the bank! And least they're honest there!"

For Ford Tractor, the major issue then was the changing nature of the small American farm--the small family farms were going away, and these small farms were a major source of sales for tractors. Further complicating it, Ford Tractor used independent, regional distributorships to work directly with the dealers. This is something that I had to study--two step distribution. When times were good, everybody was making money, then the recession hit and the farms began to die. At that point, dealerships and the distributorships, and Ford Tractor also suffered.

One of the things that we were evaluating is the necessity of independent distributorships between Ford and the dealerships. So, this experience at Ford Tractor gave me my first understanding of retail distribution. That's why I've been at the forefront of saying that the automobile industry is going through the same situation.

Dave (Source)

A TURNING POINT came in 1968 for Dave's career when a friend called him, soon after the establishment of J.D. Power and Associates, to say that there was a new opportunity in the automobile market. At the time, the marketing research and advertising firms could only serve one client in each industry, and this Japanese company was not represented. His friend mentioned that the company had launched and flopped introducing a new vehicle ten years before, and they were staging a comeback on the US market with another new car.

Dave asked him, 'What's their name?'

His friend replied, 'Toyota.'

A few years later, work with the company accounted for almost 75% of their revenue.

SM: How did you sign on Toyota as a client?

JDP: I had a problem getting in to see the Toyota people. They were small but they hired a few Americans to help bolster their US operations here in California. I called to see the manager in charge of advertising and market research, but he told me not to waste his time by meeting since they had already engaged another company. Apparently I was too late, and I was not part of the manager's circle of suppliers.

So, on a cold-call, when I was returning from another client meeting nearby, I stopped by their headquarters and spoke with the receptionist. She told me, 'he already said he didn't want to see you, he wishes you would stop bothering him.'

Then in the lobby, after seeing a brochure for their forklift operations, I asked her if I could speak to the man in charge of that section, and she told me to go find him in a back building.

When I got there, I told him that I knew more about forklifts than anyone west of the Mississippi (thanks to my Ford Tractor experiences) and made a deal to get him a report about the general state of the fork lift market. He was so delighted with the work that he introduced me to his counterpart in the automotive division.

Thanks to him, the next day I had a meeting with an older Japanese gentleman. We exchanged business cards. I looked at his, he looked at mine, and his said "Tatsuro Toyoda." I came back the next day with a contract.

Mr. Toyoda took out his pen and signed.

(Source)

SM: How did you turn your work with Toyota into broader automotive work at J.D. Power and Associates?

JDP: Toyota became a big and important part of our business. Over time I saw the risk of having too much of business with one major client. And, I had a desire to conduct some studies on issues that would be useful to a broader group of clients. I was thinking of these as independent studies where the market research company owns the data. But had to do independently--meaning without the commissioning of a client like Toyota or Honda. I sold that study for $2,500. Mazda didn't want it--but other companies did. I did the study on speculation, with my wife tabulating the data on a spreadsheet designed to organize by the vehicle's mileage. We spoke with the first 1,000 buyers and we had more than a 50% response rate [ED note: high even by today's standards].

I came home one night and she said Mazda has an O-ring problem. When the vehicles had about 35,000 miles, one out of five had an O-Ring failing. That was the fastest launch of any company. And, it was the most profitable breakthrough we had ever made because we owned the data.

SM: Where did you learn to rebound? How do you become immune to rejection?

JDP: It's a trait that was developed over time. I was much more reserved in those days. I learned that I needed to change and adapt to the situation. I figured out where I could make calculated decisions to do things differently.

One was the study of consumer reactions to the new Mazda rotary engine--and breaking the rules of the market research departments by doing the study independently and selling the information to subscribers throughout the auto industry.

That experience helped clarify for me that management was not getting good, straight information, when the senior level executives were the last to know about problems. I stuck with it and was able to show that Mazda had issues that needed to be addressed.

Working with the Detroit auto companies is another story of overcoming rejection. That took tenacity, and perseverance. It took time to show them that we were not out to "get them. " We focused on making sure that they understood that we were just trying to bring a better understanding of the consumer to their companies. Over time, little by little they began to trust us as we were able to show them the details and implications of the data and information.

SM: What was your experience with the market changes that happened in the industry during the 1980s and 1990s?

JDP: We gathered the top 500 car dealers about three times a year. I invited the management expert, Peter Drucker to be the opening speaker in 1991 and share his views on how to run a business.

We wouldn't allow the public or the press to sit in on these discussions, which provided a better opportunity for candor and an exchange of different ideas. He opened the meeting with,

'I'm here to wake you guys up. Look, I'm not going to tell you how to run a car dealership, because you know how to do it better than I ever could. But I will give you some insight on what's going on in business today.'

I asked the first question. I thought the dealers would really appreciate his views on the industry--this was in 1991, when GM was losing market share for the last ten years while newer companies like Toyota were growing like gangbusters.

He replied, 'I am not an expert in the auto industry. You are all better suited to answer that question than I am. But, I can tell you one thing. When the gods want to get even with a car company, they send them 40 years of good fortune.'

(Source)

That was a pretty profound statement that elegantly summarized what was happening at that time. The bloom was coming off of GM's rose after 40 years of success.

Well now, you've seen what's happened with Toyota in the last five years? They just hit 50 years in the market. And now, the new GM is back growing again...

What Drucker was really saying is that people who build the company are retired or out of the business after 40-50 years--they were the ones that started and made it grow. What happens is the people who take over for those earlier generations think they know it all, and don't appreciate what went into those earlier and more challenging times, and they likely don't know how to react make it keep growing when things slow down. These later generations often take a lot of credit for the success of their founders that preceded and got them to where they are.

This is part one of a two-part article. Part Two of the article will be published here http://www.huffingtonpost.com/steve-mariotti/.

Special thanks to Lauren Bailey for assistance with this article.