Co-authored by Samantha Peters

The verdict is in. Jian Ghomeshi was found not guilty in all charges laid against him--four counts of sexual assault and one count of overcoming resistance by choking. Ghomeshi dodged a bullet or, more correctly, a potential jail sentence--18 months for sexual assault and a potential life sentence for overcoming resistance by choking. This case is significant for many reasons, but we would like to highlight the problems with relying on an inherently adversarial system, which prioritizes the rights of an accused over the rights of survivor(s), especially where sexual assault is concerned.

We propose a re-imagining of future sexual assault trials in order to respond to the realities of sexual assault survivors while also respecting the rights of an accused. As Black and Indigenous feminists with an interest in criminal defence, we understand the importance of these rights and we want to emphasize that we are not calling for a lesser standard or a flipped presumption of innocence when it comes to sexual assault charges. Rather, we are calling for a more nuanced discussion about the realities of both sides of the coin: the accused who faces the state and the survivor who faces their aggressor.

Since the trial began, there has been much speculation that the system--the criminal court system--does not believe survivors. There have been many articles that have spoken about believing survivors, how to support complainants, and the thin line between a defence lawyer defending their client, as far as possible, versus "whacking the complainant." Let us be clear, by the very fact that the charges made it to trial, means that someone, at some point in the criminal justice system, believed these women. We believe these women too. We believe all survivors of violence, especially sexual violence. However, what is also clear is that our courtrooms are not safe for sexual assault complainants/survivors.

Many individuals tweeted about the trial or about sexual assault using the hashtag #IBelieveSurvivors or variations of the hashtag. These people tweeted passionately about safety issues for survivors of violence and highlighted that the legal system is biased against sexual assault survivors. Perhaps, we also need to consider other ways that the criminal justice system can be accountable to sexual assault survivors. For instance, the Integrated Domestic Violence Court provides one judge to hear both the criminal and family law cases, where the central issue is domestic violence. The question is, could this work in the context of sexual assault cases? Should a special court dedicated to hearing sexual assault cases be a future consideration?

In 2014, Justice Robin Camp, a Federal Court judge, revealed the misogynistic assumptions about sexual assault survivors' experiences. These assumptions presume that sexual assault survivors can just prevent the assault from happening in the first place (as if they carry the burden) by just keeping their knees together.

In an effort to shield his own assumptions about the truth of the survivors' experiences, Justice William B. Horkins writes in the Ghomeshi decision,

"Courts must guard against applying false stereotypes concerning the expected conduct of complainants. I have a firm understanding that the reasonableness of reactive human behaviour in the dynamics of a relationship can be variable and unpredictable. However, the twists and turns of the complainants' evidence in this trial, illustrate the need to be vigilant in avoiding the equally dangerous false assumption that sexual assault complainants are always truthful. Each individual and each unique factual scenario must be assessed according to their own particular circumstances." (para 135).

Respectfully, while Justice Horkins says one thing, that the courts must be cautious in applying false stereotypes, he fails in refraining from assuming that survivors are liars. Though Justice Horkins had a tough job, it is words like his coupled with Justice Camp's words, why many survivors do not come forward (save for all the other reasons like time, energy, or resources to even make a complaint).

We believe that creating courts dedicated to hear sexual assault cases have the potential to create a "safer" space for survivors. As part of these courts, judges would also be required to undergo social context education about sexual assault law and its meeting with race, class, gender and other intersecting and/or interlocking marginalizations. In particular, judges should be familiar with the particular circumstances of sex workers and other criminalized populations who are survivors of sexualized violence. Such education would also allow for critical examination of mainstream discourse that re-victimizes survivors. The education would also unpack the hidden patriarchy and misogyny in the context of gender-based violence. These courts would operate on a trauma-informed foundation, understanding the complexities in survivors' reasons for inconsistencies in their testimony.

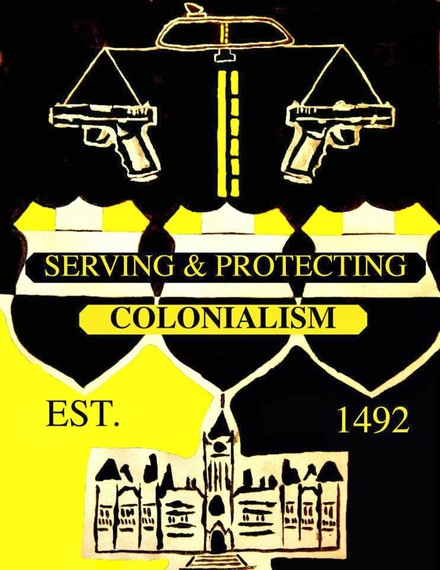

While we believe in the presumption of innocence for the accused, we also believe in acknowledging the tenacity for survivors to step forward and to tell their own truths, on their own terms, including those who do not rely on the justice system. Survivors deserve justice. Period. However, in light of the above, we also believe that relying on the prison industrial complex does not necessarily respond to these issues in a transformative way. When it is predominantly Black, Brown, and Indigenous bodies, specifically women, being criminalized and thrown into prisons, we know that seeking convictions does not automatically translate to justice. We must be cautious of the complexities of testimony, both from the perspective of the accused and the survivor.