The former world champion Vladimir Kramnik won the London Chess Classic, a tournament that brought the English capital close to its former glory. London was the world chess center in the mid-19th century when the first two important tournaments were organized: the knockout event in 1851 and the round-robin in 1862, both won by the German master Adolf Anderssen, one of the greatest chess attackers. Did the current tournament eclipse the events played roughly 150 years ago?

Anderssen did not like the playing conditions in 1851. The chairs and tables were too low for him, the chessboard too big and the players were confined to a small place. But the German master would have loved to play the London Classic this month. The organizer Malcolm Pein and his team created a great spectacle by inviting formidable players and by presenting the event in an attractive way to visitors and to online fans. Of the three London Classics, this one was the best.

Chess and tennis

It has been an old tradition to invite presidents, prime ministers, mayors and other well-known personalities to make the opening move in chess tournaments. The tennis star Boris Becker opened the London Classic on Magnus Carlsen's board with the move 1.e4.

Lots of chess players picked up tennis. There were times when we spent more time with Boris Spassky on tennis courts than across the chessboard. Once in Tilburg we came to the tournament hall with tennis bags just in case our chess game ended early. The Dutch organizers didn't like it. "Gentlemen, you are at the wrong place," they said. "Wimbledon is across the Channel." Now tennis stars visit chess tournaments. With Becker's king-pawn move the London Chess Classic was on its way.

Starting fast

Carlsen took charge quickly, jumped into the lead after three rounds with wins against David Howell and Hikaru Nakamura. Against the top American GM, Carlsen was able to create a powerful storm. You can scroll to the end of the column to replay the games.

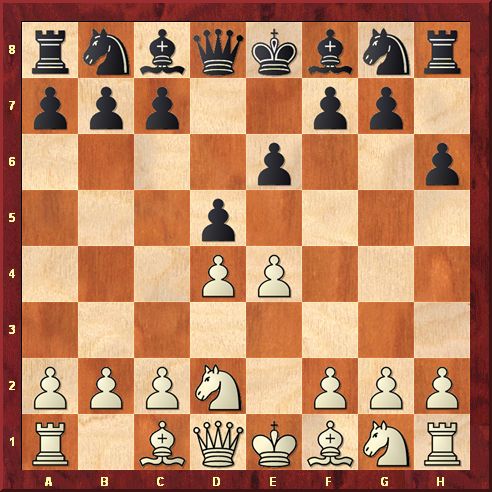

Carlsen - Nakamura

The queenside was wiped out and black's rooks are ready to invade white's position. White has to be quick and must take advantage of the knight on f6 - the only tactical weakness in Hikaru's position.

Position after 29 moves

30.h4 Qg6 31.Rxf6! (Magnus is not risking anything with the exchange sacrifice. He splits the black pawns into three islands and can pick some of them off at will. Moreover, Hikaru would have to give up the active play and defend.)

31...gxf6 32.Qf4 Rb2 (The stubborn 32...Rd8 is better.) 33.Bh5 Qg7 34.Bf3 (Protecting the g-pawn, white's knight can leap to h5.) 34...Ra8 (Black had to crawl back with 34...Rd8, for example 35.Nh5 Qg6 36.d5 Bc8 37.Nxf6+ Kg7 38.Nh5+ Kf8 39.Rc1 Rb7 with a playable game.)

35.d5 Bc8 36.Nh5 Qf8 37.Nxf6+ Kh8 38.Rc1! (The rook is going to attack the black king and Hikaru can't do much about it. The main threat is 39.Rc7 and 40.Rxf7!) 38...Kg7 (After 38...Rb7 39.Rc6! wins.) 39.e5! dxe5 40.Nh5+ Kh7 41.Be4+ (After 41...f5 42.Rc7+ wins.) Black resigned.

It seemed Carlsen was going to win another event. He performed admirably in the last two tournaments, sharing first prize with Vassily Ivanchuk in Bilbao and with Levon Aronian in Moscow, each time increasing his rating by a few points. But his drive in London suddenly stopped and he was unable to win a game. When he finally won, beating Michael Adams, he was neck and neck with Kramnik. The Russian GM passed him the next day and in the last day of the event even Nakamura sneaked ahead of him.

There is something puzzling about the way Nakamura fights back. He may fool around, slip into a terrible bind, hover between loss and survival, but he is always waiting for the right time to ambush his opponents. His game with Anand is typical.

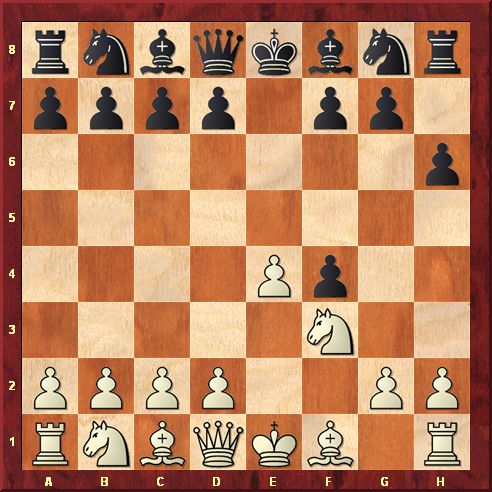

Anand - Nakamura

When you watched the opening moves, it was clear that Nakamura was not in Kasparov's coaching grip anymore. The American would get low marks for his opening play in the King's Indian defense, wasting time and allowing Anand free advance on the queenside. Hikaru tried to create a messy position, but he was on the verge of being smashed quickly. The world champion was already close to winning after 21 moves. And then something happened. Anand played indecisively and Nakamura turned the game on a dime, threw his pieces at Anand's king, and when the smoke cleared, he was up in material.

Position after 21 moves

22.Kh1?! (Anand makes room for the bishop to go to g1, but the move is tactically flawed, although white still keeps the advantage. 22.bxa7 Nh7 23.Kh1 Qh4 24.Bg1; or 22.Rxa7; or 22.Qc2 were better choices.) 22...Bf8! (Nakamura's defense and counterattacks in this game are based on several deflections. This is the first one.)

23.d6 (After 23.Bxf8? Nxe4! opening the road for the black queen to h4 gives black a deadly attack, for example 24.fxe4 Qh4 25.h3 Bxh3 26.Be7 [or 26.Kg1 Bxg2 27.Kxg2 Qh2+ 28.Kf3 Nh4 mate.] 26...Bxg2+ 27.Kxg2 f3+! 28.Rxf3 Qh2+ 29.Kf1 Qh1 mate.

Anand keeps his options open, although he could have included 23.Rxa7 Rb8; but dangerous for him is 23.Bg1 Nh4 24.hxg3?! (24.Nxe5 Bh3!) 24...fxg3 25.Qe1 Rg7 26.Be3 Nf5! 27.exf5 Ne4! wins.)

23...a6 24.Nc7 Rb8 25.Na5 Kh8 26.Bc4 Rg7 27.Ne6 (Anand eliminates the light bishop, an important piece in black's attack.)

27...Bxe6 28.Bxe6 gxh2 29.Nc4?! (The momentum switches after the knight move. Anand should have played 29.Bh3 Nh7 30.Nc4 Ng5 31.Bf5 with advantage.)

29...Qe8! (Not only attacking the bishop, but threatening to jump to b5 at the right point. The tide is turning, but the chances are still roughly equal.)

30.Bd5 (The bishop would not be able to help the white king, but it was not too late for 30.Bh3 Qb5 31.d7! Nxd7 32.Bxf8 Ngxf8=)

30...h4! (With the light bishop out of the way, the h-pawn opens up the white king.)

31.Rf2 (31.Kxh2 h3 32.gxh3 Nh4 transposes.) 31...h3 32.gxh3 (The white pawn on h3 protects the black king.)

32...Rc8 (The white pieces are entangled and black is able to play on both wings.)

33.Ra5 Nh4 (33...Nd7 34.Bb4 (34.Ba3 Ne7 35.Rxh2 Nxd5 36.Qxd5 Qg6 37.Qd1 Rxc4-+) 34...Ne7 35.dxe7 Rg1+)

34.Kxh2 Nd7?! (Hikaru makes a human move. The computers figured out a beautiful deflecting sequence instead: 34...Nxd5! 35.exd5 Rg3 36.Nd2 Qh5 37.Qf1 Bxd6 38.Bxd6 Rc1! 39.Bxe5+ Kg8 40.Bxf4 [After 40.Qxc1 Nxf3+ 41.Nxf3 Qxh3 mates.] 40...Rxf1 41.Nxf1 Rxh3+ 42.Kxh3 Ng6+ wins.)

35.Bb4 Rg3 36.Qf1 Qh5 (Black aims his forces at the f3-pawn.)

37.Ra3 a5? (Throwing the advantage away. Again, 37...Nxb6 with the idea 38.Nxb6 Rc1! wins for black.)

38.Be1 Rxc4 39.Bxc4 Bxd6 40.Rxa5? (Anand played this error with eight minutes left on his clock. He would have been still in the game after 40.Rd3 Bc5 41.Be6.)

40...Bc5! (Breaking down the defense of the f3-pawn.)

41.Be2 (Black wins also after 41.Rxc5 Nxc5 42.Be2 Nb3 43.Bc3 Nd4 44.Bxd4 exd4 45.Bd1 d3 46.Qxd3 46...Nxf3+ 47.Bxf3 Qxh3 mate; or 46.Ra2 Nxf3+ 47.Bxf3 Rxf3-+; 46.Kh1 Ng2 47.Qxg2 Rxg2 48.Rxg2 Qc5-+)

41...Bxb6 42.Rb5 Bd4?! (Hikaru is complicating his task. After 42...Bxf2 43.Bxf2 Nxf3+ 44.Bxf3 Qxf3 45.Rxb7 [or 45.Rb1 Rg6 46.Rxb7 Nf6-+] 45...Nc5 46.Rb8+ Kg7 47.Rb4 Nd3 black wins.)

43.Bd1? (The last mistake. 43.Rd5!? was the only way to fight back, for example: 43...Nf6 44.Rd8+ Ng8 [or 44...Kh7 45.Rd6] 45.Rxd4 exd4 46.Bd1 Ng2 47.Qxg2 Rxg2+ 48.Rxg2.)

43...Bxf2 44.Bxf2 Nxf3+ 45.Bxf3 Qxf3 46.Rb1 Rg6 47.Rxb7 Nf6 48.Rb8+ Kh7 49.Rb7+ Kh6 (White's position is hopeless: he loses the e-pawn and his king is still under attack.) White resigned.

Four Tops

Kramnik's victory was inconspicuous, but very efficient. He finished undefeated, drawing with the superstars and smashing the four lowest rated players - all Englishmen. The organizers again used the soccer scoring system to determine the final results: three points for a win, one point for a draw, no point for a loss. Nakamura was the only player who profited from it.

It may look confusing for many players who are used to the traditional values with one point for a win and a half point for a draw. But after having fun with the three-point system, the organizers will have to send a traditional crosstable to FIDE for rating. In this form it can be compared with other tournaments and evaluated correctly.

Still, Carlsen added a few points to his rating and may soon find out how lonely it is at the top of the FIDE list as did Bobby Fischer in 1972 when he was above Spassky by 120 points.

As the world champion Anand knows, he should be performing better than the 50 percent he managed in Bilbao, Moscow and now in London. He called his latest results disastrous, slipping to the fourth spot on the next FIDE rating list. We expect the January 2012 ratings of the top four to be: Carlsen 2835, Aronian 2809, Kramnik 2801 and Anand 2799.

King's gambit and other jokes

For the Armenian grandmaster Levon Aronian chess is a dialog between two people taking place on the chessboard: each move is a statement you can either agree or disagree with. These conversations expanded outside of the chessboard in London. Each round, one of the nine players was free to give a commentary on the games and on chess in general. It sparked great debates, almost as exciting as the games themselves. Chess players love to hear what the superstars have to say. We don't hear them very often, but in London we could.

Even the legendary grandmaster Viktor Korchnoi, 80, appeared on the stage with the commentators. He came to London to play a simultaneous exhibition. Throughout his career he played more than 5000 tournament games, averaging more than 70 games a year. The patriarch of Soviet chess, Mikhail Botvinnik, recommended to play 60 games a year.

Korchnoi still has strong opinions about the way chess should be played professionally. He chastised Nigel Short for playing "a patzer-like move 3...h6" in the French Tarrasch 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nd2.

He also disapproved Short's choice of the King's gambit, calling it a joke. But what was Luke McShane's answer to the gambit? The very same move 3...h6, after 1.e4 e5 2.f4 exf4 3.Nf3.

The game quickly turned into Bobby Fischer's set-up after 4.d4 g5 5.Nc3 d6 that the former world champion recommended in his famous 1961 article "A Bust of the King's Gambit." McShane, who played a marvelous tournament, later won the game. Chess works in mysterious ways. What may seem to be a weak move in one position, could be the beginning of a strong, playable defense in another.

Ignoring Korchnoi's comments, Nakamura chose the King's gambit in the last round against Michael Adams. Hikaru was outplayed and busted after 34 moves. Magic happened again and by move 41 Adams resigned. Carlsen, who was accused by Korchnoi of hypnotizing his opponents into making errors, put it succinctly: " Put your opponents under great pressure and they will make mistakes." Perhaps we can add that the King's gambit helped Magnus win the tournament in Medias, Rumania, in 2010.

Clash of cultures

There seems to be a pattern in the criticism leveled by some graduates of the Soviet Chess School at the young western talents. Vladimir Kramnik thinks, for example, that they should be more serious in their preparation. Carlsen and Nakamura put their hearts into actual playing, instead. Each of them tried to learn more about chess by taking lessons from Garry Kasparov. It's over now, the youngsters left him. It is easy to imagine Kasparov forcing them not only to play precisely on the chessboard, but also trying to influence their lifestyles. Transplanting the strict Soviet chess discipline into the free-spirited young Westerners turned out to be a challenge. It worked better for Carlsen, but Nakamura's coaching relationship with Kasparov ended after he finished last at the Tal Memorial in Moscow last month.

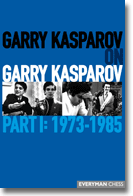

Kasparov showed up in London promoting his newest book Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov, Part I: 1973-1985, published by Everyman Chess. It is a nice addition to his monumental nine-volume work on his predecessors, on the opening revolution in the 1970s and his matches with Anatoly Karpov. This time, Kasparov writes about his career up to the end of the 1984/85 suspended world championship match. He was 21, the same age as Carlsen today. The 520-page book is based on his previous works such as The Test of Time, Child of Change and Unlimited Challenge, but goes beyond them. He includes 100 games, improves on his previous comments and on analyses by other writers.

Nakamura took a rather simple view of Kasparov's accomplishments: "His strength was in openings. You look at middlegames and endgames and I am quite convinced there are other players who were better than he was but he was able to get advantages out of the opening, so that was his strength. And when he wasn't able to do that that's when he lost his title to Kramnik [in 2000]."

Kasparov and Kramnik in London this month

Kasparov is well aware of what others say. He wrote in his book: "Throughout my life it has been said that I won mainly thanks to deep and comprehensive opening preparation. The art of preparation has been a distinguishing feature of many world champions and has always furthered the progress of chess thinking."

Note that in the replay windows below you can click either on the arrows under the diagram or on the notation to follow the game.

Photo images by Ray Morris-Hill.