"Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were." -- Marcel Proust

Proust's In Search of Lost Time is perhaps the most famous exploration of memory, with associations sparked by sensory cues like the famed madeleine. Our memories are fundamental to our sense of self, our relationships, and our behaviour. And yet, as Proust recognized, they are less reliable than they seem.

Cognitive psychologists have long proposed that memories are reconstructed over time, from Frederic Bartlett's 1932 experiment where participants were tested over a span of years on their recollection of a Native American legend called "The War of the Ghosts" they read in an initial session. Bartlett found that over time, memories of the story became "schematized" -- participants remembered the general gist of a story but lost details, and often replaced exotic and foreign items in the story with things that were more familiar to them. Hunting seals, an action foreign to Bartlett's Edwardian English participants, was replaced with going fishing; canoes were replaced with boats.

Other findings demonstrating the fallibility of memory abound. In 2001, Daniel Schacter categorized the "seven sins of memory," classifying seven shortcomings of memories further grouped into three sins of forgetting, three sins of distortion and inaccuracy, and the singular "persistence," the inability to forget something even when we'd be better off to do so, as in post-traumatic stress disorder. Research has found no correlation between our certainty in a memory and its actual accuracy -- so-called "flashbulb memories," memories for events that feel particularly detailed and vivid (for example: where were you on 9/11?), are just as prone to inconsistencies as more mundane memories, despite high confidence in their accuracy. Similarly, psychologist Elizabeth Loftus' work on eyewitness accounts has shown they are unreliable and highly susceptible to manipulation through carefully-framed questions.

From the perspective of neuroscience, the alteration of memories over time was less intuitive. Pioneering work by Donald Hebb, Eric Kandel, and many others all suggested that memories should stabilize over time through what Hebb coined as a "fire together, wire together" process. The strengthening of synapses formed memories, and once formed (or "consolidated"), they were thought to be stable. The process of reconsolidation, recently in the news as a potential target for treating PTSD, offers a mechanism through which established memories can be adjusted and altered. Each time a memory is retrieved, it is reactivated, placing it in a labile state where it is susceptible to change. It is then "reconsolidated," or stored again in the brain.

The idea that memories are susceptible to change is worrying -- we have faith in our own recollections and rely on our memories in all aspects of life. But the malleable nature of memory isn't necessarily a bad thing -- it also serves as the basis of our ability to update and integrate information, to form narratives and make sense of our experiences. Schacter himself suggested this, proposing that the "sins" of memory are actually byproducts of otherwise adaptive features, and that they can sometimes be adaptive in and of themselves. To return to the example of PTSD, the malleable nature of memory allows us to remove the negative emotions associated with particular memories. Memories can also be distorted in self-serving ways, protecting a positive and consistent self-image. One of Schacter's seven sins is bias -- including a tendency to recall our previous attitudes (for example, political opinions) as more consistent with our current beliefs than they actually were.

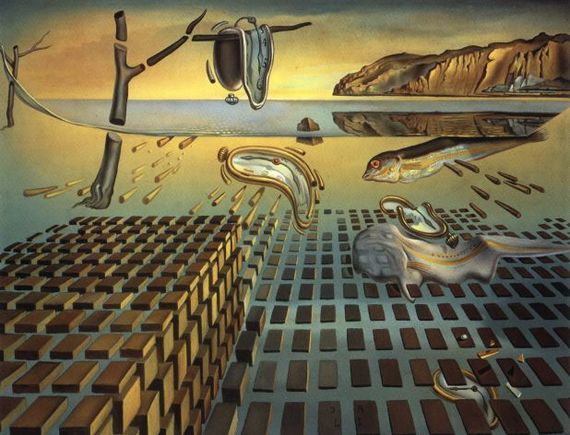

Proust was far from the only artist who realized that our memories were less than perfect. In Salvador Dali's The Persistence of Memory, melting clocks juxtapose the painting's title to suggest that while memory persists, it does so in a way that is not necessarily true to its original form. Its lesser-known companion, The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory, takes things a step further -- breaking down the original painting into brick-like units. One interpretation is that Disintegration is inspired by physics, a representation of matter consisting of atoms never quite touching. It is equally possible to interpret Disintegration in terms of the science of memory, where our recollections are deconstructed and reassembled, taking on slightly different forms each time.