Thomas Dolby's works "hold up," as it were. His five primary studio albums (including the wonderful, recent A Map of the Floating City -- also an immersive online game) auditorily evoke more pure cinéma than most movies. Meanwhile, his efforts in music video, film scoring and technology define pioneering. He puts on a treat of a concert, he launched the 21st century for twelve years as music director of the TED conference (Technology, Entertainment and Design), and his digital jams may well inhabit your mobile communication device. This week, he brings his new D.I.Y. Film Festival award-winning debut film The Invisible Lighthouse to the American Film Institute in Los Angeles. I ask him about it, and about its place in his storied career.

It's a film that I made over the winter -- English winters being rather miserable, I decided to try something a bit different, and close to where I live on the English coast, there is an old lighthouse that's been there since 1792, and it's closing down later this year -- partly because there's less need for lighthouses now, because of satellite navigation. And partly because the coastal erosion is eventually going to undermine it, and it'll fall into the sea. So they're shutting it down, and it's a very emotional thing for me, because I grew up around here, and I fell asleep with the flash of the lighthouse on my wall.

It's got an interesting history, which, among other things, it's on this island which was formerly a military testing zone for experimental weapons. And you're not allowed to wander around out there, because there are unexploded bombs.

Undeterred, the intrepid Mr. Dolby went anyway, guerrilla style, and lensed his film. He adds that the place is also nicknamed the "British Roswell" due to local UFO lore -- a well-documented (albeit alleged) landing nearby in 1980 had servicemen jotting down hieroglyphics from a "flying saucer" hull, with strange binary codes telepathically beamed into their brains, etc. (I love this guy.)

"So the film revolves around that, but it also ties in my family history, which goes back generations in the area," he reveals.

Some of my childhood memories around here are actually implants as well. Like, I have this memory of this big building that my ancestor built, that was used for a classical music festival, and when I was 10, it burned down in this terrible fire. I remember watching the roof burning across the marshes. And years later, my mum told me, 'Well, we were actually hundreds of miles away the night that it burned.' But I've heard the story so many times that it's like it's burned onto my retina.

"It's really a film about memories, it's about how memories become amplified over time," he says of The Invisible Lighthouse.

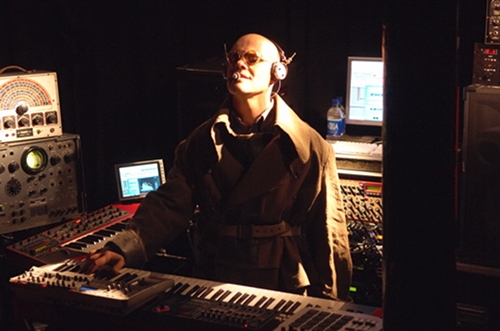

That's the long way around saying that it's a self-contained film, but when I perform it live, I do the music and the narration live on stage. And it's evolving: I'm just right now in the middle of writing a cue that I'll play next week -- it's a new piece for one section. Later in the year I hope to do a full tour of the U.S. with it. I'm hoping to play old cinémas and theatres.

(Did I mention that I love this guy?)

Mr. Dolby's trajectory through the cinématic arts is vast and varied, from doing music for acquired tastes as diverse as Willard Huyck's Howard the Duck and Ken Russell's Gothic (which both sound wicked cool), to hanging out with his friend J.J. Abrams. He tells me about bringing the highly-attentive Abrams to TED, about Abrams showing him around the Star Trek Into Darkness set, and in turn showing the director his music studio. "We dig each other's toys," he grins. I remind Thomas that years ago, his rave-up of Slava Tsukerman's Liquid Sky in an interview turned on a lot of video-store lurkers to that movie.

"I suppose I was always a bit of a film fan," he explains,"and I tended to like sort of unusual, experimental things that were very atmospheric.

And I often felt, when I was writing songs, that I was writing a score for a sort of experimental sci-fi movie -- very often parallel universes, and alternative realities, and things like that. So, you know, a song like 'Airwaves,' you can imagine this sort of post-apocalyptic world, where it's very dangerous to go out in the subways, and everything's electrified, and the air is not safe, and so on. And there's a sort of underground ham radio movement. I tend to sort of, you know -- my tribe are really the underdogs, the resistance -- that's my tribe.

This concept is echoed in "Dissidents" (one of my fave songs ever, from his truly thrilling 1984 album, The Flat Earth). Thomas is amenable to the parallel. Then we delve back further, to discuss the milieu in which he created "Leipzig," one side of his very first single.

I think that 'Leipzig' was a nod in the direction of a movement, an electronic music movement that kind of fed off the Cold War atmosphere of Eastern European cities and so on. And there was a generation of us who were very inspired by side two of (David Bowie's) Low, and things like that. Along with listening to Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream and people like that. And that was sort of at the height of the Cold War, really, so, being a little island off the coast of Europe, we were very affected by that.

I think that what was going on at the time was that a lot of people were using synthesizers and electronic instruments, and were very mesmerized by what machines sound like when they're just being themselves. You know, that it's not just a case of us programming them, they have a personality of their own which is different from organic instruments. And that's certainly true. But actually I very quickly found that what I really wanted to do with electronics was something a lot warmer. I wasn't interested in the coldness. I was interested in telling stories, using electronics as a canvas, really -- or a palette to paint on a canvas.

And so I've always done that, really. I do consider myself primarily sort of a storyteller. So there was definitely a very visual element to it. Plus the fact that I tend not to -- I don't write relationship songs: I don't write songs in the moment, about people leaving text messages for me, and things like that. That sort of day-to-day life, master of urban style is not something that I relate to, really.

But I am really strongly influenced by my environment, by where I am in the world, where I'm working, places I travel to, and the weather, and the atmosphere in general. So that's what makes the music cinématic, I think.

I ask if The Invisible Lighthouse, billed as a work-in-progress, will change.

It's going to go on evolving, and I may eventually have one or more other musicians on stage with me, when I tour with it later in the year. I've got some shows in the U.K. in the spring, in May -- including the cinéma in my hometown, which is going to be quite interesting. You can see the lighthouse from the cinéma! Most of the audience there will know every shot -- you know, where I took it and stuff. My region of East Anglia has been done, by other people -- but never quite like this.

Unconsciously (brain implant?), I parallel the theme of Mr. Dolby's recent Time Capsule tour, wherein he inventively invited fans and friends to record their views of the future in his eponymous silver airstream-cum-contraption. I've asked the sci-fi-humanist likes of Ray Bradbury and Leonard Nimoy this, and so I ask the tech- as well as eco-savvy Thomas: Where will we be in 100 years?

Well, if we don't think of something, we may not be here at all. But I'm actually optimistic that we'll think of something. And I think, actually, if there's hope, it's with the scientists. Because the politicians and the corporations sure as hell aren't going to solve it," he reflects. "But science will maybe come to the rescue -- and it's gonna have to. I sometimes think, you know, we're on this planet that's spinning at a thousand miles an hour, and rotating around this endless power source, and it's got a molten core, and it's got winds and tides that never stop. We should be able to figure this out. We really should.