I first heard about Leo & His Circle (Knopf, 2010), Annie Cohen-Solal's ambitious, but bizarrely unfocused, biography of the art dealer Leo Castelli, two summers ago, when I was sipping Campari and sodas in Montauk, Long Island, with Leo's son, Jean-Christophe. I have known Jean, as his friends call him, since 1986, when I began working for his father. Because Jean and I are the same age, we were often assigned to the so-called "kids' table" at gallery dinners. We've been friends ever since.

I first heard about Leo & His Circle (Knopf, 2010), Annie Cohen-Solal's ambitious, but bizarrely unfocused, biography of the art dealer Leo Castelli, two summers ago, when I was sipping Campari and sodas in Montauk, Long Island, with Leo's son, Jean-Christophe. I have known Jean, as his friends call him, since 1986, when I began working for his father. Because Jean and I are the same age, we were often assigned to the so-called "kids' table" at gallery dinners. We've been friends ever since.

Having read an early version of Cohen-Solal's biography, (which first appeared in French), Jean said Cohen-Solal viewed Leo's immigration to the United States, and his subsequent cultural assimilation, as the quintessential Jewish story of the 20th century. Cohen-Solal, he said, was exploring his father's influence as an art dealer within the centuries-long context of his family's Jewish heritage.

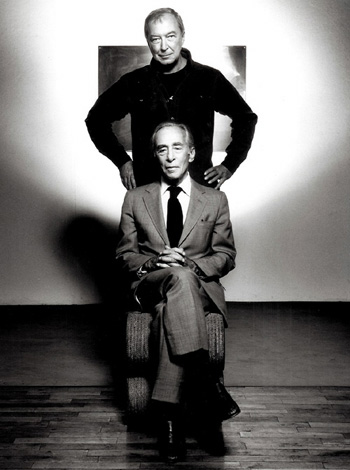

This struck me as strange. After all, wasn't Leo, the tireless early promoter of such larger-than-life talents as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and James Rosenquist--not to mention one of the chief architects of the American contemporary art market as we know it--also a font of contradictions? That he remained so staunchly loyal to his artists, for example, but was, at the same time, a serial womanizer; that he could be so gracious publicly and such a private tyrant; that he revered intelligent, strong-willed women, while acting so appallingly sexist; or that he so often appeared confident, smooth, jaunty, but could, and would, behave so helplessly--this was more than enough fodder, it seemed to me, for a fascinating account of his life.

Besides, Leo had never spoken of his Jewishness during the four years that I worked for him. Indeed, as Patty Brundage, one of the gallery's former directors recalled, "Holly Solomon used to come into the gallery in September or October and say, 'Happy New Year,' and Leo would never know what she was talking about."

Still, having once dutifully performed my prescribed tasks at the Leo Castelli gallery, first as a front desk girl and archivist, then as Leo's personal assistant, at 420 West Broadway, and, finally, at 578 Broadway as a co-director of the space and a curator of his private collection, I now considered Cohen-Solal's book a must-read.

Still, having once dutifully performed my prescribed tasks at the Leo Castelli gallery, first as a front desk girl and archivist, then as Leo's personal assistant, at 420 West Broadway, and, finally, at 578 Broadway as a co-director of the space and a curator of his private collection, I now considered Cohen-Solal's book a must-read.

The biggest problem with Leo & His Circle is Cohen-Solal's voracious appetite for overarching themes. There are too many narrative threads for even her to keep track of, and they dangle like half-gnawed carrots, for pages, chapters, until one loses all hint of their initial flavor.

In lieu of examining her extensive research, Cohen-Solal resorts to incongruous pronouncements, a disturbing use of exclamation points, and passages that read like "notebook dumps" as Dwight Garner points out in his New York Times review.

In her quest to paint the most elaborate possible picture of Leo, Cohen-Solal zooms out so far that idiosyncratic contours of his extraordinary character appear muddled. The first hundred pages of Leo & His Circle are an example of this. And, although I enjoyed learning more about the early years of his marriage to Ileana Sonnabend, and the couple's escape from Nazi-occupied France, for a lively depiction of the New York art scene in the 1940's and 1950's, your money would be better spent on Mark Stevens and Analyn Swan's mesmerizing biography, de Kooning: An American Master (Knopf, 2005).

Lastly, and perhaps most annoyingly, at pivotal moments, such as Leo's first visit to Rauschenberg's studio, Cohen-Solal invokes Claude Levi-Strauss' description of New York. Closing her chapter on Leo's discovery of Jasper Johns, she flashes back to Gertrude Stein and Picasso. Yanking us again and again from the narrative, she then showers us with petty errors: Jerry Ordover was Leo's longtime lawyer, not his accountant. Morgan Spangle was not the manager at Castelli from 1988-94, as Cohen-Solal states in her epilogue; but from 1984-90 (he then returned from 1996-98). The name of Leo's assistant, co-director, and employee of 21 years, Patty Brundage, is erroneously spelled Patti. The (male) free-lance curator, writer, and lecturer, Patterson Sims, is referred to as "she." ("So much for basic scholarship," wrote Sims, in an e-mail.) The galleries with whom Leo famously shared artists were NOT his satellites, as Deborah Solomon aptly observes in the New York Times Book Review. And these are only details noted in passing.

Ultimately dismayed by a book I found more slap-dash than vivid, I plumbed my own archive of memories, and came up with this admittedly humble verbal snapshot:

It is October 1989. Jean and I are seated at the kids table for a gallery-hosted dinner honoring The Bear, a film produced by Claude Berri. Berri collects art, when he isn't making movies. As a cultural icon--and a Frenchman--he is exactly the type Leo was constantly striving to impress. The dinner is attended by a smattering of art world heavyweights, from the art dealer Larry Gagosian to the artist David Salle, as well as Hollywood-types such as the then-sizzling Sandra Bernhard, and the actress Kathleen Turner.

I am seated next to Jean, who begins waxing about his youthful idolization of Turner. He and I compare notes on the steamy star of Body Heat, who is smiling and laughing across the room.

Then suddenly, Turner stands up. Winding her way through the crowded restaurant, the blonde bombshell moseys over to Leo, then 82, apparently to pay her respects. Leo and Turner exchange pieces of paper, which Jean and I assume to be their phone numbers. Jean looks crestfallen. I pat his hand. And with a weariness that extends well beyond his years--he has just turned 26--Jean sighs, "I've never been able to figure out why my father seems to have so much more fun than I do."