Interviews by email are a function of the busy life and digital existence most of us lead these days, and while a convenience they sometimes backfire in their intention. My desire in talking to Trevor Paglen was to get at the motivations behind his work, which for many years has involved activity that investigates covert government operations (classified defense activities and other such "secrets") in photographic images that seem consequently bound up in some degree of thrill-seeking given their potential (legal) risk. As a New Yorker piece on the artist detailed, "He has aimed his lens at a National Security Agency eavesdropping complex in Sugar Grove, West Virginia; a space-surveillance transmitter in Lake Kickapoo, Texas; and a secret C.I.A. prison outside Kabul."

Untitled (Reaper Drone), 2010. C-print, 48 x 60 in (121.9 x 152.4 cm). Courtesy of Metro Pictures

VORTEX 3 IN Sextans (Inactive Signals Intelligence Spacecraft), 2009. C-print, 48 x 60 in (121.9 x 152.4 cm). Courtesy of Metro Pictures

Paglen here, and in other interviews, plays down this aspect of his work despite the great lengths required to track and capture the often (intentionally) blurry, abstract results. The conceptual underpinnings of the work, namely the contingent nature of images ("It's about taking what might be a familiar image and reinscribing it with something else"), may drive the process more than its physical pursuit, but nobody spends weeks and months - 20-30 trips alone to the Nevada Test and Training Range (N.T.T.R), for example - chasing glimpses of spy satellites, domestic drones, secret detention facilities and test sites, without a strong desire to. Indeed, as I write this, Paglen has returned to documenting an invisible radar system that surrounds the United States in his ongoing project, The Fence, begun in 2010.

The Fence (Lake Kickapoo, Texas), 2010. C-print, 50 x 40 in (127 x 101.6 cm). Courtesy of Metro Pictures

Granted, his latest project, and the occasion for this interview, The Last Pictures, departs from this model. Its generation of 100 images nano-etched into a thin, silicon wafer (by MIT scientists) sent to space, and built to last eons such that it will "explain to somebody in the future what happened to all of the people who built the dead spaceships in orbit around the earth", conversely involved the direct collaboration of a government-friendly corporation, EchoStar Satellite Services, who contract with the military.

A generous, highly intelligent artist with a PhD in geography, Paglen happens to come from a military family so an ambivalent, vacillating relationship to its culture may be endemic. Regardless, the exhibition at Metro Pictures, Paglen's first solo show with the gallery, featured a very engaging and laborious installation of both select photographs from the disc sent to space, as well as - intriguingly - a grid of those rejected (82 additional images). A video of the satellite in orbit along with notebooks and other ephemera were also made available, detailing the thought process and science behind the project in an archival fashion.

Installation view, 2013. Metro Pictures, New York.

The Last Pictures is in part a response to, and reaction against, its famous 1977 precedent, the Golden Records. The latter, consisting of phonographs ranging from greetings in 55 different languages to an hour-long recording of brain waves, was launched into space aboard the Voyagers 1 and 2 spacecraft. Conceived by none other than Carl Sagan, it too was meant to be a message to whatever intelligent alien the spacecraft might encounter, though its utopian tenor - what Paglen understandably takes issue with - precluded references to human fallacy and malice. Ie., there were no references to disease, conflict, etc.

The Last Pictures (The Tower of Babel), 2012. Digitally retouched c-print, 71 3/8 x 92 1/8 in (181.3 x 234 cm). Courtesy of Metro Pictures

Rooted in the presumption that no image can posit universal meaning or truth about humanity, a postmodern premise that says as much about our current worldview (or Paglen's vision of it) as did the Golden Records, The Last Pictures is nonetheless a very compelling project. It evokes the basic human impulse to mark one's place in the world, or in this case, the universe, to say "we were here!". Like a reverse form of (cosmic) anthropology, it defines an image of "self" through the illusion of "other", the latter being wholly inconsequential to the endeavor (it is well established that anything in geostationary orbit has a lifespan measured in hundreds of years, not billions). And it is from this point - the impossibility of the project - that I begin the interview, a series of devil's advocate positions that Paglen rather kindly engaged until busyness prevailed, and (perhaps) patience waned. Artists understandably get tired of explaining their work, so whatever the outcome I'm grateful for any chance to poke around in their brains. As Carl Sagan said, "We can judge our progress by the courage of our questions and the depth of our answers."

The Golden Records, Courtesy NASA.gov

JUH: There is something simultaneously quixotic and futile about your project, The Last Pictures, a kind of hubris that assumes other beings would care about a species as inconsequential, cosmically speaking, as humans. Perhaps that betrays my own cynicism about our species, but do you really believe the photographs you've gathered will be meaningful (let alone comprehensible) to future "aliens"?

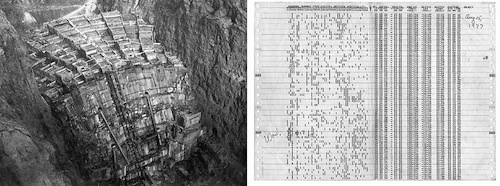

The Last Pictures (Construction of Hoover Dam; The Wow! Signal), 2012. Two gelatin silver prints, each frame size: 24 7/8 x 32 7/8 in (63.2 x 83.5 cm). Courtesy of Metro Pictures

TP: I don't think The Last Pictures will ever be "found" - I think of them more as images that will haunt the earth, watching us and whatever may yet come. The Last Pictures will be images detached from history and culture. In this way, the closest analogy we have to something like that is probably cave paintings. Do cave paintings mean anything? Not really, but I for one am happy to have them. Having said that, the project's main audience is obviously us here and now.

JUH: I don't know if I see cave painting as detached from history and culture. They are commonly held to symbolize a stage in human development in which abstract thinking develops, when we become creative, etc. The point zero of art history, if you will, in the diachronic model, anyway. So maybe you can explain what I'm missing in the analogy?

TP: Yes, that's certainly the common understanding of cave paintings, but those interpretations are constantly changing. The most recent research, to my understanding, has shown that the great "creative awakening" or that moment around 40,000 years ago when cave paintings seem to have first emerged is being complicated. More recent archaeological evidence seems to be doing away with the idea of a "creative awakening," and showing how the paintings emerge as part of a much longer continuum. Also, the interpretations of cave paintings change with the times. The early interpretations by Abbé Breuil held that the paintings were straightforward representations of hunt scenes and such; later scholars like Mircea Eliade and David Lewis-Williams interpret paintings in terms of shamanism; other scholars like Norbert Aujoulet seem are more resigned to the idea that there's something deeply enigmatic about them and that's that. The point is that the cave paints don't speak. They are impressionistic. In short, they are images. It's productive and fun to try interpreting cave paintings but ultimately they can't teach us anything beyond what we imagine them to be. In this sense, they are like mirrors more than anything else.

LA CROSSE/ONYX II Passing through Draco (USA 69), 2007, C-print, 59 x 47 1/2 in.

Courtesy of Altman Siegel, San Francisco; Metro Pictures, New York; Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne

JUH: You've been quoted as saying "I don't put work in an art gallery because the next day I want people to march in the streets", conveying instead a desire to evoke a sense of the sublime in your work, which you define as "the fading of the sensible, or the sense you get when you realize you're unable to make sense of something". The latter statement seems in keeping with your criteria for selecting photos for The Last Pictures, what Katie Detwiler paraphrased as "images that were unstable or undermined their own truth claims" yet at odds with what the New Yorker calls your impatience with "artists who don't take art's social purpose seriously." How do you reconcile the apparent contradiction in these expressed viewpoints?

Installation view, 2013. Metro Pictures, New York.

TP: I don't see a contradiction at all. I think there's potentially something productive about images that are unstable. In an ideal situation they can open up or help us "unglunk" what we think we know and ask us to question our assumptions about the world around us. In this sense, I'm very influenced by modernist theories of art, but of course realize that we're not living in the 1920s or 30s and that the aesthetic-political strategies that were relevant then might not be the same as what might be relevant now. Nonetheless, there was a transformative ethic underlying the work of that era. An ethic that has been unfashionable for quite some time now but is something I'm interested in and think is relevant. I believe that art can make relevant and progressive contributions to culture and society. Call me a sucker :)

JUH: Well its a romantic position, that invocation of the "avant-garde", one that I share. There was resistance and counter-discourse in a lot of that period's output (I teach many aspects of it in my modernism class at SVA) ala the anti-bourgeois, anti-academy sentiment that ran through the best of it, IMHO. So I still value the utopian prospects of that radicality too, and very much try to incarnate it among my students, and my own practice. But this was a very expensive project that likely wouldn't have been viable without the commitment of Creative Time, who commissioned, and Nato Thompson, specifically (who happens to be your close friend). How do you see it as being "transformative", and what do you hope its impact will be?

Installation view, 2013. Metro Pictures, New York.

TP: Sure, The Last Pictures cost money to make happen, but not nearly as much and a lot of people think. It's about 1/10th the cost of the site-specific installations they do at the Met, and about 1/100th the cost of Olafur Eliason's waterfalls. Yes, Creative Time fundraised for the project, so did MIT, and so did I personally. Creating artworks, writing and publishing novels, poetry, music, or conducting art-historical research requires support. So does everything else in the world, from physics to fish and wildlife management to human-rights advocacy.

As for the "transformative" potential of The Last Pictures, I think that's a very strong word. No artist has ever made a work of art that single-handedly transformed anything. The best we can do is to propose ways of seeing and thinking, hopefully in the service of a better future. I hope that the Last Pictures is a project that, in the first instance helps us think about images and their relationship to history and culture. The broader concern has to do with trying to think through our impact on the earth, and our relationship to the past and to the future. For me, it's been a very humbling project to work on.

JUH: Humbling how so?

TP: Working on The Last Pictures meant trying to think through an impossible series of questions. It meant working on a project that is both ultimately nonsensical and at the same time seemed to carry an enormous ethical burden. That's a very difficult space to spend so much time living in and trying to think through. At the same time, dozens of people from very diverse backgrounds dropped what they were doing to focus on making the Last Pictures happen. It was incredible and humbling to be in the middle of the project for all of those reasons.

Courtesy of Metro Pictures

JUH: In your previous photographic work documenting spy satellites (The Other Night Sky, 2007-10) and invisible radar systems (The Fence, 2010), the allure of danger and the near impossibility of the task (logistically and politically) infused the otherwise abstracted, often blurry results with a sense of portent, a voyeuristic thrill. The Last Pictures arguably represents the greatest "difficulty factor" thus far (in the amount of money and coordination it required), if not the same level of potential (legal) risk, whereas recent work documenting domestic drones suggests a return to the latter. How much does the precipitous nature of a project fuel your process?

TP: I'm still working on the Other Night Sky and The Fence, and am actually doing quite a lot of work on The Fence at the moment. I don't think there's anything particularly dangerous about those projects. Today I'm on the road shooting somewhat sensitive sites and by far the most dangerous part of my day was driving through a blizzard.