A wave of new books and shows has washed into the summer of 2014, all built around the theme of the greatest secret of World War II: the making of the atomic bomb. Why do we keep returning to the scientific breakthrough that took us into the atomic age?

Sixty years after the world's first atomic bomb was unleashed, we are in the midst of an explosion not just of books but a musical and a television series, all focused on the making of the world's first weapon of mass destruction. And no wonder. The story has the perfect plot: a struggle between good and evil on a global scale with a cast of heroes -- brilliant young scientists and the women they loved. A race against the villains from without (Hitler) and, after the race was won, within (Joe McCarthy.) Also a spectacularly cinematic setting in the high desert of New Mexico: a secret city built on a mesa surrounded by a mountain wilderness.

The action takes place in the years when World War II was far from won. Six decades later, as that war fades from living memory, we are reminded again, by new books, an Off Broadway musical titled Atomic playing in New York, as well as a new cable television series called Manhattan which debuted on July 27. (The Manhattan Project was the overall name for the effort that produced the first atomic bombs.)

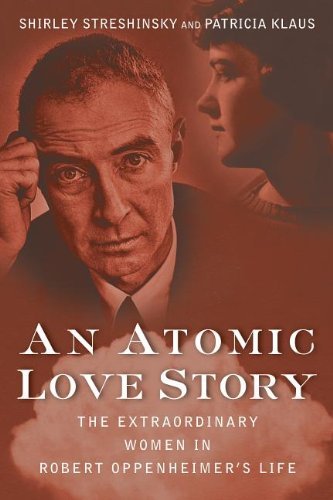

The revival began last year with the non-fiction The Girls of Atomic City about the women who worked at the Oak Ridge, Tennessee site. Next up was An Atomic Love Story: The Extraordinary Women in Robert Oppenheimer's Life, the book I co-authored with Patricia Klaus, the result of 10 years of research centering on the man known as the "father" of the a-bomb, and the women he loved. Then came The Wives of Los Alamos, a novel set at the secret New Mexico site where the bomb was actually built, where the average age of the scientists and their wives was 26.

Coming attractions: another novel titled The Atomic Weight of Love described as "the story of modern feminism through the eyes of a woman in Los Alamos." Also underway: a non-fiction book called The General and the Genius about the excessively cranky General Leslie Groves who was in charge of the project for the Army and, of course, Robert Oppenheimer, the genius at its core. The man who was described by one friend as "brilliantly endowed intellectually" with "good wit and gaiety and high spirits."

And another added: "His mere physical appearance, his voice, and his manners made people fall in love with him -- male, female, almost everybody." Elegant, handsome, wealthy, complex -- Robert Oppenheimer was the perfect central character, the romantic leading man, around which the story of the building of the bomb could be told. And retold by an emerging phalanx of writers who cannot resist the inherent drama of a time, a place and a task that would propel the world into the dangerous new era that haunts us still. Witness North Korea and Iran. We return to the beginning, perhaps, in an attempt to divine the future.

Since the publication of our book last September, Patricia and I have been speaking to groups large and small, in bookstores, libraries, homes. Our first event was co-sponsored by a YMCA near Berkeley, where initial work on the Bomb was done. That's when we learned what a draw Robert Oppenheimer remains. The room was packed, and included a contingent of physicists who had stories to tell, almost always about Robert.

Often they offered private glimpses of the man, passed down by a teacher who knew Robert: about his intellect, his curiosity, his concern for the human condition. A woman in her 90s remembered a story he told at a cocktail party in the 1940s. And so his legend grows.

Patricia is a historian, I am a writer. In the years when we were reading everything we could find about our subjects, our first big decision was critical: We started by assuming we would do a non-fiction book, which meant we would have to do original research, turn up new material. The problem was not Robert Oppenheimer -- there were reams of material about him. But we were approaching him through the women he loved, and initially we had very little to go on.

In the case of Jean Tatlock, whom Robert had hoped to marry, we had only one memorial letter, written by a friend of the family. There was somewhat more about Ruth Tolman, because her husband had been an important physicist, and the CalTech archives had a few of her letters in its Tolman file.

And as for Robert's wife Kitty, the major Oppenheimer bios had more information on her, almost all of it negative, and most of it provided by two women who had good reason to detest her. Their acid testimony seemed to have defined Kitty's legacy. If we couldn't find a lot more on these three women, we would have to call our book a "novel," another word for fiction. Neither of us wanted to do that, so it meant we were going to have to do some prodigious digging. That's when the fun began.

We followed the most elusive leads: Patricia found a small footnote which linked Jean Tatlock to the poet May Sarton, In the Sarton archive in the New York City library, we found a cache of letters from Jean to her best friend in high school, letters that made Robert's first love come to life for us.

Our search led us to Ruth Tolman's nieces in Berkeley, Jean's nephews in New York City, Kitty's great nephew in Germany. And we were able to track down the daughters of Kitty's first husband, (a marriage that had been annulled) and found ourselves with an altogether different account than the one Kitty had offered. We tracked down some surprising sources for gossip, found a ship's log that explained a suicide at sea. Pieces of the puzzle dropped into place; clearly, others are swirling around out there, in the cities of the Manhattan project, revealing the lives of the men and women who were a part of that time and its secret places.

Next month we are heading for the library in the town of Livermore, California, home to the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, built after the war by some of the men who had been at Los Alamos with Robert. We feel sure that a few scientists will be there to tell us a story we haven't heard.