The Wild World of WONDERWALL's Music

George Harrison's blend of tablas and electric guitars furnished an appropriate musical accompaniment to the dizzying film it supported.

By Tom Fritsche

Sometime in the summer of 1993, ex-Beatle George Harrison drove to the recording studio in West Los Angeles where he was to record a brief cameo for The Simpsons. He would appear as himself in "Homer's Barbershop Quartet," an episode-long parody of his old band, and he was assured the session would be brief and discreet. His cover was quickly blown and the studio was swarmed with The Simpsons' writing staff, all professed Beatle fans, overwhelming him with more questions about the old band. Harrison glumly obliged until the show's creator, Matt Groening mentioned Wonderwall Music: a soundtrack album he'd released in 1968, and the first he'd released under his own name. Harrison perked up and started gushing. That album, he told Groening, was the most fun he'd ever had making a record--and almost no one, in twenty-five years, had ever asked him about it.

No one had asked him likely because almost no one had seen the movie. Even today, Joe Massot's Wonderwall is largely unknown, except as an artifact of Swinging Sixties psychedelia. In it reclusive, middle-aged microbiologist Oscar Collins (Jack MacGowran) becomes obsessed with the beautiful Vogue model next door (Jane Birkin) and her freewheeling world that he spies through a small hole in the wall of his cluttered bedsit. The majority of the film is an impressionistic look at Collins' transformation as he goes deeper into a bright, unhindered, paisley world (and drills more holes in the wall). As a film alone, Wonderwall has seen little reappraisal; the plot, described by author Simon Leng as "wafer-thin," doesn't develop much, leaving much of the film's action to Collins' kaleidoscopic fantasies provided by Dutch art collective The Fool. Birkin's character (eye-rollingly named "Penny Lane") is little more than a one-dimensional trophy for Collins to voyeuristically lust over and her photographer boyfriend (Iain Quarrier) to ignore, and yet Penny's beauty is enough to sink the otherwise button-down Collins neck-deep into far-out psychedelia. As such, Wonderwall's release went quietly: its premiere at Cannes in May 1968 was overshadowed by the ongoing political unrest in France (which caused the festival to end early) and the film never secured wide distribution, dooming it to an initial release on the midnight circuit in America. While an English television screening was seen by Noel Gallagher of Oasis and provided the title of his band's most famous song, Wonderwall itself is considered unmemorable; for these reasons it is primarily known for its score.

When Massot approached George Harrison in 1967 about composing the film's music, he initially demurred. After all, he'd never scored a film before (the other Beatles barely allowed him one song per LP-side on their records), and it was unclear if Harrison was even up to the task of writing a complete album's worth of music: up to that point, he had only written and released about a dozen songs. Furthermore, the large gaps in Wonderwall's dialogue meant that any music, Beatle-written or not, would be a primary focus of the film. Massot, however, assured him that anything he submitted would be used; and so, armed with a print of the film and a stopwatch, Harrison set to work. The soundtrack he delivered was a meeting of his two worlds: the blues-rock he'd been brought up on, and the Indian classical tradition that had taken all of his recent attention.

First he set to work on the Western music. Harrison booked sessions that December in London; while an exact list of the players on those sessions are unavailable, it is understood that among them were fellow Beatle Ringo Starr and good friend Eric Clapton (as well as the surprising addition of Monkee Peter Tork on banjo), though the majority of the rock 'n' roll backing would be provided by his old clubmates the Remo Four of Liverpool. Harrison himself was thought not to have played on any of the tracks--serving only as producer and composer--until the album's remaster in 2014, which confirmed a more hands-on involvement. The songs recorded range from chill pedal-rock ("Party Seacombe") to Hollywood cowboy music ("Cowboy Music", of course) to blistering psych-shredder ("Ski-ing," whose popularity has so outgrown its origin that the Harrison estate once released it as a ringtone). One vocal track, credited to the Remo Four as performers and Harrison as producer, was deemed at the time to be too far off the mark by the Beatle and went unsubmitted until Massot rediscovered it and included it as the opening theme to a 1998 re-release of the film.

For the Eastern section, Harrison assembled a crack team of Indian musicians (including master santoor player Shivkumar Sharma and Ali Akbar Khan's son Aashish on sarod) and flew into Bombay to record with them for a ten-day session in January 1968. The Indian music composed for the film would be the culmination of Harrison's sitar training from Ravi Shankar (training so serious that, until later that year, Harrison had fully planned to abandon the guitar entirely in favor of his new instrument), as well as his general fascination with Indian music dating back to 1965, and he was determined to share this love with the music audiences of the West. With his aforementioned two-songs-per-album quota, Harrison had had little outlet for his Indian compositions; while he'd managed to release two Indian compositions on Beatle records ("Love You To" in 1966 and "Within You Without You" the following year), he could only add touches of Indian instrumentation otherwise (contributing sitar to "Norwegian Wood"). And so, though the EMI studio in Bombay was not as technically polished as the one in London (and the soundproofing in the studio still allowed traffic noise to bleed through), these Indian sessions were a welcome release for Harrison's new ideas (a third Indian composition, "The Inner Light," was also recorded during these Bombay sessions and later saw release as the b-side to "Lady Madonna").

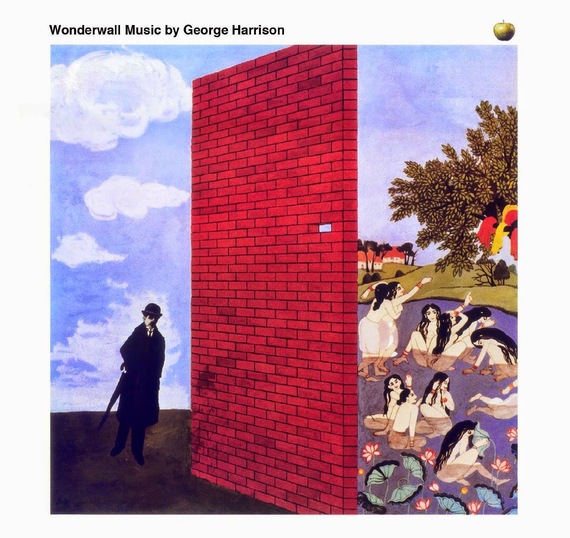

Harrison's score was released on November 1, 1968 under the name Wonderwall Music. It was the first album put out under the Beatles' new Apple label, the first credited to Harrison alone and the first credited to any Beatle without the other three. The album's release would be overshadowed by the Beatles' new album release later that month (the famous White Album); it did not chart in Britain, though it did manage a peak at number 49 on Billboard charts in America (despite being a soundtrack to an unavailable film) before fading away into out-of-print obscurity for many years. Though George Harrison would later contribute individual songs to films like Porky's Revenge, Lethal Weapon 2 and Shanghai Surprise (the last of which saw Harrison serve as producer), Wonderwall is the only film to which Harrison provided an entire score. Excepting Paul McCartney's minimal involvement in his credited score for The Family Way--largely arranged by George Martin--Wonderwall is the only film scored by any Beatle.

Even if few listened to it or remembered it--to the point that asking George Harrison about it would leave him stunned--Wonderwall Music did what it set out to do. Its blend of tablas and electric guitars furnished an appropriate musical accompaniment to the dizzying film it supported, and it provided an easy introduction to Indian music to several of his fans who, like Harrison, were intrigued by Hindustani classical instrumentation. And finally, it proved that Harrison that he could carry his own weight for an entire collection of music: to the world, to the other Beatles, but most importantly, to Harrison himself.