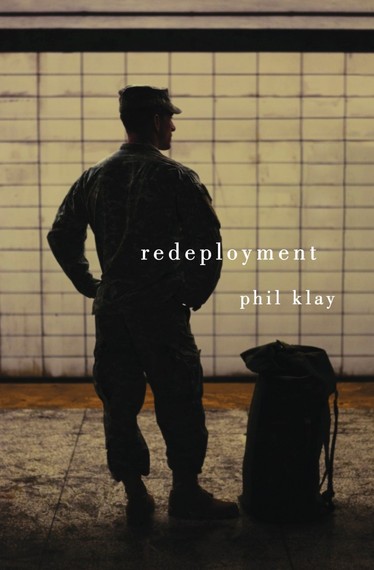

Phil Klay joined the Marines in 2004 after graduating from Dartmouth and served in Iraq in 2007 and 2008. His first book, Redeployment, a collection of stories based on his service and his return to civilian life, won the 2014 National Book Award. The New York Times called it "the best thing written so far on what war did to people's souls." It has been described as "extraordinarily powerful" by The Washington Post, "heartbreaking" by GQ, and a book of "sheer emotional torque" by The Guardian.

As part of Words After War's December Book Club, Phil Klay answers a few questions from Victoria Kelly, author of When the Men Go Off to War.

***

Victoria Kelly: You begin your collection Redeployment with a story about coming home. There is a remarkable poem by W.S. Merwin called "When the War is Over," published in 1993, that I have gone back to time and again in my attempts to understand the military experience:

When the war is over

We will be proud of course the air will be

Good for breathing at last

The water will have been improved the salmon

And the silence of heaven will migrate more perfectly

The dead will think the living are worth it we will know

We who are

And we will all enlist again.

In Redeployment, your narrator expresses something similar: "As glad as I was to be in the States, and even though I hated the past seven months and the only thing that kept me going was the Marines I served with and the thought of coming home, I started feeling like I wanted to go back." Why do you think so many servicemembers, spanning so many wars and generations, have shared this desire to return to war, despite its horrors?

Phil Klay: There are so many reasons. For that character, part of it is that all his instincts are now geared toward combat, and so the whole way he responds to his environment is something that would be useful in a war zone, but is really difficult at home. He feels like he no longer fits.

But there's more. First off, the sense of camaraderie in a war zone shouldn't be underestimated. That character talks about the moment of realizing that everybody's life depends on him not screwing up, and that he depends on them. There's an element of horror, I guess, in that line, but the implied trust and interdependence is quite powerful. That's deeply satisfying for many people. I think of the George Oppen poem, "Of Being Numerous," "I cannot even now / Altogether disengage myself / From those men // With whom I stood in emplacements, in mess tents, / In hospitals and sheds and hid in the gullies / Of blasted roads in a ruined country."

Then there's the sense of shared purpose. There's a bit in Sebastian Junger's War where he says, "These hillsides of loose shale and holly trees are where the men feel not the most alive--that you can get that skydiving--but the most utilized." The smallest things can take on a vital importance--tying your bootlaces correctly could huge consequences--and the stakes of what you're doing are clear. You don't have to believe in the overall mission to believe that the decisions you make on any given day outside the war could be momentous.

In comparison, civilian life can seem colorless, the soldier or Marine suddenly having to make decisions about what brand of baby wipes to purchase. It's easy to suggest that all this stuff is meaningless... war is where the really important stuff happens. That's not true--the stakes of building a family, building a stable life and being a good member of a community and a good citizen of your country--those stakes are huge, just harder to see. So yes, deployment can be horrific, but it can also be fun, it can feel full of meaning, and it can be a reason to put all the problems of civilian life on hold for a while. Part of the process of truly redeploying is finding that same sense of purpose in civilian life--I think that's part of why you see so many veterans getting involved in service organizations like Team Rubicon or The Mission Continues--it allows them to take the same drive that led them to join the military in the first place and reap some of the same satisfactions in a very different context.

VK: In "After Action Report," you write about the blurring of truth and fiction: "There were the memories I had, and the stories I told, and they sort of sat together in my mind, the stories becoming stronger every time I retold them, feeling more and more true." Do you think there is a difference between books that interpret the wartime experience fictionally--like The Things They Carried or All Quiet on the Western Front--and works of nonfiction--like We Were Soldiers Once, and Young or What It is Like to Go To War?

PK: It depends on the book, I suppose, but I don't read Dispatches so differently from how I read All Quiet on the Western Front. Fiction and nonfiction just offer the reader different tools--and they pose different challenges. It think it's easy to cheat your material, whether you're writing fiction or nonfiction, but the temptations lie in different directions. With fiction, you're tempted to make the events of the story conform to how you'd like to see the world, and yourself, and your worldview. You can skip past challenges you wouldn't like to confront. With nonfiction, since the expectation is that everything is true, it's easy to pay less attention to why it's true. And you get to pretend you're being objective. I think of Robert Graves, here: "The memoirs of a man who went through some of the worst experiences of trench warfare are not truthful if they do not contain a high proportion of falsities." Memory is a tricky thing, after all.

VK: The author and fighter pilot James Salter once wrote, "Sometimes you are aware when your great moments are happening, and sometimes they rise from the past." While you were serving in the Marines, did you see yourself as playing a small role in the larger movement of history? Do you think it is possible to be aware of "great moments" during the chaos (or tedium) of war?

PK: That's why I joined the military--to play a small role in the larger movement of history. I did have a sense of something changing when I was overseas--I was in Iraq during the Surge, in Anbar province, when violence radically plummeted--though I clearly didn't know what the ultimate outcome would be (and, obviously, still don't). That said, I had a very limited sense of how I could meaningfully affect things. There's a bit from Kenneth Koch's poem, "To World War II," where he speaks of the war whispering in his ear, "'Go on and win me! / Tomorrow you may not be alive, / So do it today!' How could anyone ever win you? / How many persons would I have had to kill / Even to begin to be a part of winning you? / You were too much for me, though I / Was older than you were and in camouflage." In the moment, I didn't the best I could. I believed in what we were trying to do, and I hoped that the movement of history would turn out to be less cruel than it has been.

VK: You've talked about civilian apathy, which is something that has frustrated many of the veterans I know. With the rise of terrorism in the West, most recently the Paris attacks, war is moving into civilian lives in America in a way that it hasn't since World War II. Do you think public support of veterans now is greater than it was when you were serving during the war in Iraq? In your opinion, what does the opposite of civilian apathy look like?

PK: I'm not sure war has come into civilian lives--these attacks are horrific but they do not make San Bernadino, for example, a war zone. If the presence of mass shootings made a place a war zone, then we would hardly need Islamic terrorism to consider ourselves at war. There does seem to be a lot of fear currently infecting our politics, though, which isn't likely to lead to sensible responses to our current threats.

The opposite of civilian apathy is engaged citizenship. It's neither deifying nor demonizing nor pathologizing veterans, but taking them and the job they have done seriously. It also means taking our role in the job as citizens seriously by holding elected leaders accountable.

VK: When you won the National Book Award, you became one of the "must-read" military writers. When you talk, people listen; your tweets about welcoming Syrian refugees into America got a great deal of media attention and support. Do you feel a pressure to be a voice for veterans now, or to incorporate themes of war or politics into what you write next?

PK: I don't know about that. The Syria tweets just hit a particular nerve...they also meant a few angry messages from veterans who don't feel I'm a "must-read" military author at all.

I don't think winning the National Book Award has changed the way I approach writing. At least, I hope it hasn't. There are subjects that trouble or confuse or fascinate me, subjects that I feel nervous writing about. I wrote Redeployment with this image of a long line of veterans waiting in line to kick my ass if I screwed it up. I try to keep that kind of pressure on myself. And I have friends I trust to read my work and tell me when I'm failing. That's probably the most important part--surrounding myself with smart people who challenge me, who see the world in different ways but who are genuinely committed to conversations about our disagreements.

I guess what I mean is that I don't feel an obligation to write about war or politics, necessarily, but I do feel the same obligation I always felt--to approach whatever my subject is as honestly as I can, and to be interested in my own failures so that I can learn and write better.

***

Words After War is a nonprofit literary organization with a mission to bring veterans and civilians together to examine war and conflict through the lens of literature.

Follow Words After War on Twitter @WordsAfterWar

Follow Phil Klay on Twitter @PhilKlay

Follow Victoria Kelly on Twitter @VKellyBooks