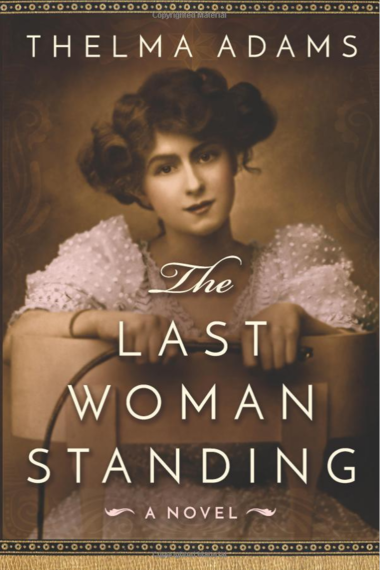

Thelma Adams' new novel, Last Woman Standing, is based on the real-life story of Josephine Marcus, a singer in the Old West who became the common law wife of legendary lawman Wyatt Earp, lived with him for 46 years and wrote a book about their life together. In an interview, the long-time movie critic and entertainment journalist explained what captured her attention in Marcus's story and how Earp ended up buried in a Jewish cemetery.

How did you first learn about Josephine Marcus?

Google is a wonderful thing - and an incredible rabbit hole. I saw an image of Wyatt Earp's grave in a Jewish cemetery in Colma, California. I'm Jewish and this struck me as strange and interesting: how did he come to be buried there? And in answering that question I found Josephine Sarah Marcus, an Eastern European Jew who settled with her family in the Bay Area after traveling through the Panama Canal from New York. I read her published memoir, I Married Wyatt Earp, discovered that it was not entirely reliable, found a different version entitled Wyatt's Woman: The Unvarnished Memoirs and Recollections of Josephine Sarah Marcus Earp (1860-1944) edited (and self-published) by Earl Chafin. Neither of these are works of literature, nor are they the navel-gazing, scab-picking of, say, Kathryn Harrison's The Kiss or Augusten Burroughs' Running with Scissors or what we've come to know as contemporary confessional memoir. But they contained fascinating nuggets about Josephine and Wyatt and made me hungry for more. I filled in the gaps with biographical fiction.

What were your most important sources for research?

I began with Josephine's memoirs and studied them both for what they contained and what they left out. Then I tacked back to the Earp canon - Stuart Lake's Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal; Casey Tefertiller's excellent Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend; Allen Barra's Inventing Wyatt Earp: His Life and Many Legends; William M. Breakenridge's Helldorado: Bringing the Law to the Mesquite and Paula Mitchell's And Die in the West: the Story of the O.K. Corral Gunfight. There are a lot of books on Earp, and most have paragraphs, perhaps a few pages about Josephine. I read Harriet and Fred Rochlin's Pioneer Jews: A New Life in the Far West and a micropress book by Ron W. Fischer entitled The Jewish Pioneers of Tombstone and Arizona Territory. There are a number of excellent diaries of the period, including Tombstone from a Woman's Point of View, the dispatches that the 25-year-old journalist Clara Spalding Brown sent back from Tombstone to the San Diego Daily Union. Really, Nell, taking down my sources again and spreading them on the bed, I realize how many books, pamphlets, maps and magazines I tapped to create my biographical fiction, how much highlighter and how many sticky tabs I used. When I embarked on the project, Ann Kirschner's nonfiction book, Lady at the O.K. Corral: The True Story of Josephine Sarah Marcus Earp, had yet to be published by Harper Collins in 2013. So, as I picked up my story again for the final push, I dipped into that book, too.

How was she influenced by her Jewish upbringing? How did it affect the way people saw her?

Josephine was raised in the faith with all the rituals that implies: attending synagogue, Friday Sabbath and candle-lighting, observing the holidays, cooking a related cuisine. Her father, a baker, made the challah. Her home-town San Francisco had a thriving Jewish community. And, yet, the German Jews looked down on her people, the Eastern European Jews. When she left home to marry a gentile, Josie's mother sat Shiva, with all the angst that brought to the family. And, yes, in Tombstone people saw her as a Jewess, which made her exotic, along with her looks. But she was not the only Jew in town, although the rest were predominantly male: merchants, bankers, miners or gamblers. Yes, they were outsiders but in a boomtown where everything was new, where inherited wealth was nonexistent and places of worship were just being built, it was not so difficult to be an outsider. However, the "virtuous" women and wives did attend church and their social lives were imbedded in church functions, picnics and charities. Josephine, by not joining in, by refusing to enter a church, was therefore distanced from a certain circle of women.

What about her experience as a performer? What does that show us? How does it relate to her insistence on being the one to tell Wyatt Earp's story?

San Francisco was an enormously cultural city, rich with opera, theater and classical music. Josephine frequently attended the theater with her older sister and they were mad enthusiasts. Even Tombstone hosted plenty of traveling theater and music.

As a performer, Josephine loved the idea of being in the spotlight, at the center of things. She had the looks but lacked the talent. She couldn't sing. She could dance alright. When she discovered she had horrible stage fright at her first performance, she realized that while she loved the life of the theater she would never be a star. She viewed herself as a romantic heroine in the mold of Josephine in Gilbert and Sullivan's H.M.S. Pinafore, a wildly popular operetta of the time, or Rebecca of Ivanhoe, which had been turned into a play.

What this shows the reader is that Josephine had a dramatic and cultured personality, a desire to stand out, to be at the very least the heroine of her own life story. And, so, she also wanted to ensure that Wyatt was always seen as a hero. Even after the Vendetta, when Earp led a posse and shot down, one by one or two by two, those who had assassinated his favorite brother Morgan (and public opinion became divided), Josie kindled the light of his image. He was a hero in her eyes - and she staunchly maintained that view, to the point of attacking those who said otherwise in later life beyond the scope of this particular novel.

How would she want to be remembered?

She would want Wyatt Earp to be remembered as an unqualified, unsullied hero (there are many who disagree with this portrayal). For herself, she would want to be recognized as the love of his life, the keeper of his flame and a strong, sexy woman who embraced life on the frontier and survived, often in style. She saw the west when it was wild, met many of the key players and lived to tell the tale. She herself made the choice to be at the center of things, a hair's breadth from history - not keeping house and tending children in the anonymity of an arranged Jewish match in San Francisco. She wanted to be remembered as a unique individual in extraordinary times.

What do we learn from her relationship with Albert? Her relationship with Johnny Behan's son Albert reveals the tender, caretaking, protective side of Josephine. With Albert, we see an element of her that is not sexual, where her beauty is unimportant. Their relationship allows us to see her more dimensionally, and to see the goodness and generosity in her heart, and her playfulness. Also, she is really on the cusp of adulthood at the gateway between her teens and twenties - and sometimes she is emotionally closer to Albert the son than Johnny the father.

Why did you decide to tell the story in the first person and what helped you create her voice?

Originally, I employed multiple voices, including that of Virgil Earp's wife, Allie. Wyatt's sister-in-law wrote her own life story and had a very strong voice that spoke to me, rebuked me even. But when I committed to this novel being Josephine's story without the counterpoint of Allie's strong prairie skepticism (which I loved - she has quite the pioneer narrative according to Jane Candia Coleman's Tombstone Travesty: Allie Earp Speaks!), the novel began to coalesce.

I have used the third-person and third-person omniscient in the past, but I love the first-person, the narration of essays and introspection. I find it provides intimacy and also reveals the character's foibles and prejudices. Josephine's memoirs helped me create the voice -they were fascinating but cagey and corrective, edited by the hands of those that followed. I wanted to really see this story through Josephine's eyes, unashamed - and once she started speaking she never stopped. This perspective was all the more important to me because, having read all those books about Wyatt Earp, where Marcus got only a relatively few footnotes, a paragraph here or a page there, I wanted to reclaim her life and her part of the story even though she never carried a gun herself. The record marginalized her. History is full of women's stories clamoring to be told - and an audience of readers who welcome them.

What are some of your favorite historical details of language, clothing, and settings that helped create the characters and settings?

I worked from a large, rolled historical map of Tombstone, so I was always trying to get things right - where was the restaurant where Josephine ate on the first night; what did it look like? How far was it from the house where she stayed, and the one she built with Johnny? At first, I did too much research, always over-describing the Basque bodices, or the type of sleeve. An editor pointed out that she would ride side saddle and I spent days revising, figuring out the kind of saddle and what that would mean for her riding, where her legs would be in the stirrups. I laid out the weight of a carriage, or mentioned the name of a settee's furniture maker. I studied H. M. S. Pinafore and pinched pieces of lyrics that my characters would sing and references they would have been aware of at the time. But so few of my readers would have gotten the references - it's so fitting that the heroine of that operetta shares Josephine's name and defies her father's wishes for a good marriage by falling for a lowly sailor - so I had to find other ways to keep true to history and connect with a contemporary audience. The novel could never feel like the wonderful period rooms at the Brooklyn Museum or the Met - it had to be live and breathe. I loved that there were roses in Tombstone because they were a luxury that had to be shipped there on a long and dangerous route. And, since the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral is such an iconic event, I had to really nail down the setting using multiple sources and often conflicting first-person accounts.

What did writing about movies for so many years teach you about telling a story?

Writing about movies taught me to keep the story moving. Forward narrative motion is essential to keeping a reader's/viewer's interest. Drop anything that doesn't serve the story - and end once, with a bang, confidently. I hate movies with multiple endings that seem to second-guess each other.

People say I see with a cinematic eye but I started out in college writing poetry for the Berkeley Poetry Review with novelist Mona Simpson, children's author and artist Elisa Kleven and film producer/writer/director James Schamus. Visual images and their description have always been part of my writing palette. That said, I pay a lot of attention to the visuals. Also, I pay a lot of attention to conflict - what is the story without tension?

However, writing about movies, and Westerns in particular, left me thirsting for more female-driven stories. When I saw a movie like Tombstone, where every boot is historically accurate, every vest button a match for the past, and yet the women are not given the same detailed accuracy, I felt compelled to write the stories of these women. There are so many prostitutes in Westerns - but where did they come from? What were their stories, their lineage? More recently, when I saw Quentin Tarantino's "The Hateful Eight," where he just heaps humiliation on the female prisoner played (and Oscar-nominated) by Jennifer Jason Leigh, I felt there is my argument, if I even needed one, for writing a female-driven Western. There are so many stories that we need to tell - and the story of Josephine Sarah Marcus is the one I felt most passionate about. I could write about movies, and rail about the paucity of women characters and their treatment, or I could write a novel with a strong and sexy heroine. So that's what I did.