Dr. Kristine Stump swims alongside, and holds onto, a tiger shark during one of her research trips. Photo credit: Grant Johnson

I have been lucky enough to spend many years in the water studying and swimming with sharks to learn more about various species and how to best protect them. There are a lot of misconceptions about sharks, but to help clear up a few myths up here are five things I've learned from swimming with these amazing and important animals.

1. You're lucky to see one in the first place.

Shark have all five senses that we do PLUS two more -- a lateral line that senses pressure waves, and electromagnetic reception that picks up weak electrical fields like those given off by muscle contractions. In other words, a shark knows you're there well before you know it's near. If the shark actually does come close enough for you to see it, consider yourself lucky because...

2. Sharks are wary of humans.

In the water, we're big, weird-looking and awkward. Compared to the silent grace of most things that swim in the water, we humans are generally pretty splashy and noisy. That tends to scare animals away, including sharks. I'm 5'5", and with my fins I'm about 8 feet. That's about the same size and often even bigger than many shark species with which we share coastal habitats. Most animals, including sharks, generally don't roam around looking to pick fights with other animals that are bigger than they are. They also don't target humans because...

3. Sharks know the difference between prey and non-prey.

Sharks generally eat fish, including other sharks. And crustaceans. Some eat sea turtles. And some target marine mammals. But there is NO shark species whose diet intentionally includes humans. With all seven of their senses, sharks know what their food is. I've been in chum-laden water with hammerheads, tiger sharks, bull sharks and reef sharks, and they ignore me, going straight for the bait. Unfortunately, they're not perfect...

4. When a shark bites a human, it's a mistake.

As human populations grow, more and more people spend time in shark habitats like coastal waters. Even though sharks have all seven of those senses, they don't always get it right. For example, sometimes it's too murky in coastal waters for them to tell the difference between a school of baitfish and a group of humans splashing in the surf. Sharks don't have hands, so they test things out with their mouths. If a shark does bite a human, it usually realizes its mistake and lets go immediately. Unfortunately, we humans are pretty soft, so those accidental exploratory bites can be pretty damaging. Despite these extremely rare instances...

5. Sharks are in more danger from humans than we are from them.

It is estimated that each year, around 100 million sharks from many species are killed for the fin trade, overfishing, as bycatch on longlines, in beach nets, and from other unsustainable practices. Trade in shark parts contributes significantly to the decline in shark abundance. Additionally, many species are slow-growing, late to maturity, and produce only a few offspring every few years. Therefore, many populations can't handle current harvest rates. As top predators in marine ecosystems, sharks are important indicators of a healthy environment. If a system can support its apex predators, it means that the ecosystem is functioning as it should from the bottom up.

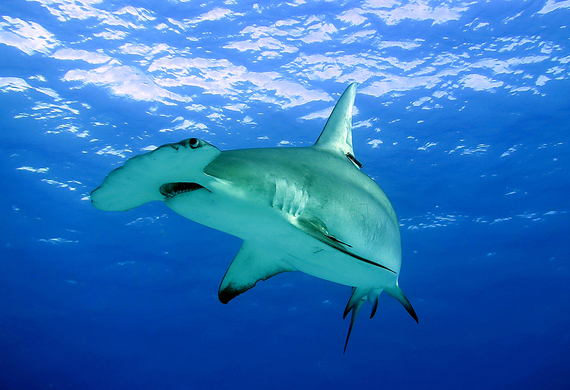

A hammer head shark in the wild as seen by Dr. Kristine Stump during one of her research trips. Photo credit: ©Shedd Aquarium/Kristine Stump

Conservation Efforts

So what is being done to help protect this species? Between 2010 and 2014, 22 Association of Zoos and Aquarium (AZA) accredited zoos and aquariums reported taking part in a variety of field conservation projects benefitting shark species. Over those five years, the AZA community invested over $2.7 million in shark conservation. Most projects were associated with population studies, conservation-related research projects, habitat protection, and visual marker tagging. Visual marker tagging efforts in particular involved collaboration with the National Marine Fisheries Service, a division of NOAA, responsible for management of US marine resources.

Over the years, Shedd Aquarium continues to research and support initiatives to protect this important species, from working with the Governor to pass legislation to ban the sale, trade, or distribution of shark fins in the state of Illinois to being one of the first zoological institutions to successfully breed zebra sharks.

--

Kristine Stump, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Research Associate at Shedd Aquarium, joined Shedd in 2014 as a postdoctoral research associate in the Daniel P. Haerther Center for Conservation and Research. Her work focuses on spawning aggregations of Nassau grouper. Dr. Stump joins Shedd after earning her doctorate in marine biology and fisheries from the University of Miami's Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, where her research focused on the effects of nursery habitat loss on juvenile lemon sharks in the Bahamas. Dr. Stump's field work on the island of Bimini at the Bimini Biological Field Station revealed that lemon sharks are highly vulnerable to habitat loss caused by human disturbances and cannot seek out new nursery grounds even if the quality of their habitat and food availability is compromised.