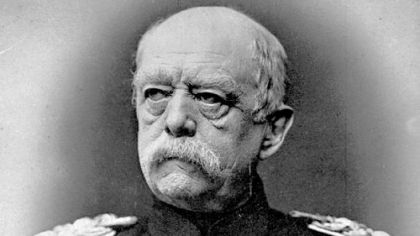

The Collapse of the Bismarckian System: Alternative Alliances and WW I

Bismarck is said to have once observed that, "German foreign and military policy was hostage to its geography." Lying astride the heart of the continent, the rise of German military power could simultaneously threaten virtually all of Europe. Bismarck's principal aim was to insure that the rise of Germany would not precipitate an anti-German alliance by its neighbors. Above all else, he wanted to insure that Germany would not find itself in a position where it would have to fight a war on two fronts concurrently.

The Bismarckian international system that he implemented had three principal objectives: maintain friendly relations with Great Britain to insure continued British neutrality, isolate France, and seek an alliance with the conservative monarchies of Austria-Hungary and Russia.

While aware of the danger of French ambitions to retake Alsace and Lorraine, Bismarck realized that France alone could not stand up to German military power. The possibility of any kind of French-British alliance, while possible, seemed remote. Britain was continuing to pursue a policy of non-involvement in European politics. Moreover, France, its historic enemy, remained a potent rival in the race to colonize Asia and Africa.

In 1873, Bismarck turned his attention to Russia and Austria, creating the "League of the Three Emperors." The League was designed to bring the conservative monarchies of Austria-Hungary, under Emperor Franz Joseph I, and Russia, under Tsar Alexander II, into alignment with Prussia. Each party was obliged to come to the others' aid in time of war. In this way, Bismarck intended to maintain the balance of power within Europe and insure that no anti-German alliance would be formed. The Three Emperors League had an inherent weakness, however. Austrian and Russian interests were increasingly at odds in the Balkans.

Ultimately, Germany would have to choose between an alliance with Austria-Hungary and an alliance with Russia. Wilhelm Fredrick I and Alexander II had both favored a German-Russian alliance. This was not without precedence. A similar alliance had existed between Catherine II (the Great) of Russia and Fredrick II of Prussia. Their mutual animosities notwithstanding, the two had signed a defensive alliance in 1764, and had collaborated in the successive partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth that began in 1772. A similar alliance would be made between Adolph Hitler and Joseph Stalin in 1939. Bismarck, however, was determined to unite the German-speaking people under Prussian leadership, and insisted on Austria-Hungary as Germany's main alliance partner. He threatened to step down as Chancellor if he did not get his way.

There was nothing inevitable about the alliance structure that would ultimately coalesce in the period from 1890 to 1910. A German-Russian alliance had always been a distinct possibility. Indeed were it not for Bismarck's opposition, it might well have come about. Such an alliance would have left Austria and France as the two "isolated" parties. Having both been victims of Prussian aggression, the two countries would have been natural allies. Moreover, their foreign policies were highly compatible. France had little interest in the Balkans and Austria-Hungary had little interest in overseas colonies. A Russian-German versus an Austrian-French alignment would have left Italy surrounded by two historic enemies and put it firmly in the German-Russian camp. Such an alignment would not only have been plausible but it would also have been more consistent with historical precedent. We can only speculate how an alternative alliance structure would have affected British and Turkish policy.

Angered by what it perceived as a lack of German diplomatic support for its gains from the Russo-Turkish War of 1777-78, Russia abandoned the pact in 1879. Bismarck tried again, creating a formal, Three Emperors Alliance. The alliance was concluded in 1881 for a term of three years and was renewed in 1884, but it lapsed in 1887. Bismarck then proposed a "reinsurance treaty" with Russia under which Germany and Russia both agreed to observe neutrality should either party be involved in a war with a third country. The fact that Russia and Germany had moved from mutually supporting each other in the event that one of them found itself at war to being neutral underscores the steady divergence in Russian-German relations over this period.

The three-year treaty remained in force till 1890. The Russians asked for a renewal, but by then Bismarck had been dismissed and his successor, Leo von Caprivi, was unsupportive. Moreover, the German Foreign Office had concluded that the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia was incompatible with the aims of the Dual Alliance between Germany and Austria.

Even though Bismarck had insisted on an alliance with Austria, he had repeatedly sought a diplomatic accommodation with Russia to forestall any kind of French-Russian alliance. Such an alliance seemed a remote possibility. Republican, revolutionary France seemed to have little in common with conservative, backward Russia. But driven by what they both perceived as an increasingly belligerent Germany, the two countries increasingly found common ground. The rapprochement was rapid.

In 1891, barely a year after the collapse of the Russian-German reinsurance treaty, a contingent of the French Naval fleet visited the Russian naval base at Kronstadt and was warmly welcomed by Tsar Alexander II. Two years later, the Russian Fleet reciprocated with a visit to the French naval base in Toulon.

The two countries agreed on a military convention in August 1892, signed by the Chiefs of the respective Army General Staffs, pledging that if either was attacked by Germany, or by one of Germany's allies supported by Germany, the other would immediately attack Germany. The agreement further stipulated that in the event of war France was obligated to mobilize at least 1.3 million troops and Russia 700,000 to 800,000. After extensive negotiations, this Franco-Russian alliance was formally accepted in both countries on January 4, 1894. The new alliance made all things Russian the height of fashion in Paris. From the Ballets Russe to vodka and caviar, Russian culture was greeted with open arms by Russia's new French allies.

In 1898, Germany enacted the first, of what would eventually be four, Fleet Acts as part of a deliberate policy of challenging British naval supremacy. The German action came at a time when London was acutely aware of a sense of imperial over reach. Great Britain remained a powerful country capable of meeting the challenge of any of its adversaries, but increasingly it was clear that it would be hard pressed to meet the challenge of multiple adversaries simultaneously.

Faced with a direct threat to its naval supremacy, the Admiralty developed and launched the dreadnought class of battleships. Named after the first ship launched, the dreadnought design offered two revolutionary innovations: an "all big gun" armament configuration with an unprecedented number of heavy caliber guns and a steam turbine propulsion system. Subsequent innovation saw the power plant converted from coal to fuel oil, increasing both speed and cruising range. These super battleships, by the standards of the early twentieth century, instantly made all previous pre-dreadnought battle ships obsolete, towering over them in both speed and fire power.

Faced with what it perceived as a direct and growing threat from Germany, Great Britain slowly abandoned its historical neutrality and began to look for allies to contain German ambitions. The search brought an unlikely set of allies, from an accommodation with the United States to an alliance with Italy in the Mediterranean and Japan in East Asia. Two additional allies, in particular, would, historically, have been highly unlikely ones.

France had been Great Britain's historic nemesis. Even after Waterloo, it remained a formidable competitor to Great Britain for power and influence around the world, and it had emerged as a strong rival in the race to colonize Africa and Asia. As late as 1898, the two countries had almost gone to war over the Fashoda incident in the Sudan. But now, British attitudes towards its historic rival began to change. In 1904, London and Paris signed a series of agreements called the Entente Cordials. The agreements marked the formal end of Britain policy of neutrality in European affairs.

There was still one more unlikely ally to join the alliance. For decades Russia and Great Britain had engaged in "The Great Game" for power and influence across central and East Asia. Russia's steady expansion to the east had often brought it into conflict with British interests in Persia and the Indian subcontinent. By 1907, however, the tensions and rivalries of "The Great Game" had been set aside for a newer and more acute concern, containing German ambitions. That year, Great Britain and Russia signed the Anglo-Russian convention.

Bismarck's carefully constructed foreign policy was in ruins. One by one, the core principles of the Bismarckian system had collapsed: Britain had abandoned its historic neutrality to join an anti-German alliance and had reconciled with Russia, its great power rival in Asia. France had ended its isolation by reconciling with its historic nemesis Great Britain and had successfully forged a military alliance with Russia. Germany now faced the one scenario that Bismarck had worked so tirelessly to avoid; powerful enemies joined together in mutual support on both its eastern and western borders. That alliance would ultimately shape both the character of the war and its principal battlefields.