H.C. Westermann, "Female Figure," 1977, wood, glass, ink, watercolor, photograph, 79 3/4 x 24 1/8 x 31 1/4", at John Berggruen Gallery.

H.C. Westermann, "Female Figure," 1977, wood, glass, ink, watercolor, photograph, 79 3/4 x 24 1/8 x 31 1/4", at John Berggruen Gallery.

Strong statements, be they in visual art or any other creative medium, are meant to leave a lasting impression. Artists take on big and important issues, be they topical or formal or psychological, and inject all the passion and analysis they can muster. Why, then, do such efforts often fall flat? In a nutshell because they end up lacking in nuance. High minded intent and powerful conviction generally equals a lot of hot air. It's one reason why the pairing of William Wiley and H.C. Westermann at John Berggruen Gallery (San Francisco) is such as event; individually each is beloved for combining rapier sharp visual intelligence with downright goofy humor. The personas are highly theatrical, but both convey a subtext of barely contained concern. They rarely take it too far because, their art tells us, they rarely get carried away with their own message.

Michael David, "The Navigator (Small)," 2010, encaustic on wood, 21 3/4 x 32 x 2", at Bentley Gallery.

Michael David, "The Navigator (Small)," 2010, encaustic on wood, 21 3/4 x 32 x 2", at Bentley Gallery.

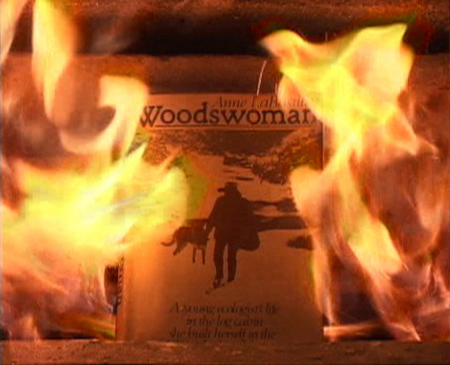

If an image can be didactic without a title, and Michael David's often are, removing the imagery, as David does in his current encaustic paintings seen at Bentley Gallery (Scottsdale, Arizona), focuses your attention first on optics. But check the title of the show's central work, "The Best Cowboys Have Chinese Eyes," and the cinematic quality of the blood red sun of a tondo, and see if that doesn't take you in some surprising directions. If the landscape's presence is indirect in his body of work, it couldn't be more explicit to both the form and content in Vanessa Renwick's current project at PDX Contemporary (Portland), "as easy as falling off a log." Given the Pacific Northwest locale, shades of Ken Kesey's Stamper family, the show conveys how immersion in the environment pushes us to anthropomorphize it. A send-up image like "flat as a board (knot)," translating a bit of tree bark and pine needles into a frontal nude, helps puncture, without contradiction, the environmental polemic.

Vanessa Renwick, "Woodswoman" video still from "as easy as falling off a log," 2010, video installation, at PDX Across the Hall.

Vanessa Renwick, "Woodswoman" video still from "as easy as falling off a log," 2010, video installation, at PDX Across the Hall.

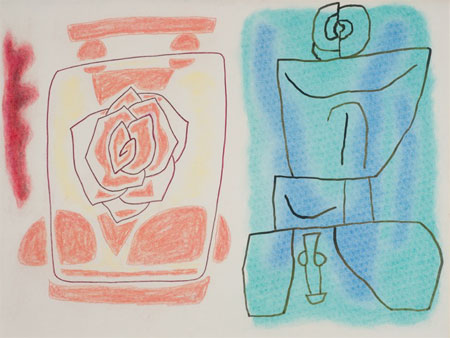

Memory and ghost stories form an engaging foundation to Augusta Wood's photographs of the empty interiors of the former home of the artist's grandparents. In this exhibition at Angles Gallery (Culver City, California) she projects old snapshots from different times in the past to re-animate those spaces, so you know just how personal these images are. The twist is how Wood is able to focus interest on the images themselves; visual experience and where we take the images trumps family biography. Nuance implies complexity, and if Wood's pictures are certainly that, the journey we take with William Brice appears to go in just the opposite direction. In an exhibition at L.A. Louver Gallery (Venice, California) covering about 25 years of stylistic evolution, it is striking how Brice moved from an overtly sophisticated interpretation of the figure to a cartoonishly simplified look. But, where humor seems to come from the core of, say, H.C. Westermann's aesthetic, Brice pretty much banishes it. His response to the human body came more and more to be informed by history and architecture, with the formal and the sensual components banging hard together only to merge seamlessly. It's a remarkable trick.

William Brice, "Untitled," circa 1984, pastel and ink pen on paper, 18 x 24", at L.A. Louver Gallery.

William Brice, "Untitled," circa 1984, pastel and ink pen on paper, 18 x 24", at L.A. Louver Gallery.

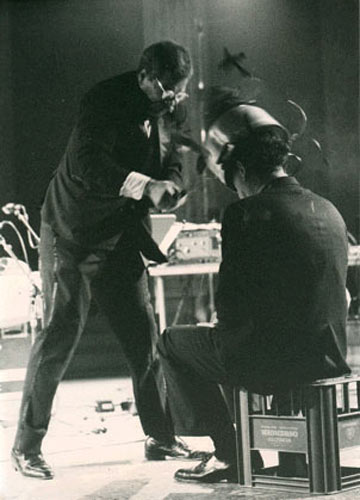

Then there is the trickster, willing to appear the fool until you immerse yourself enough to see the world through the artist's eyes. Benjamin Patterson, long beloved in Fluxus circles, has only begun to emerge from career-long obscurity in recent years. This retrospective at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston is well earned. Neo-Dada absurdity works best when the wit flows naturally and the ridiculous images and performative actions are taken dead seriously by the perpetrator. Jazz and classical music are central to Patterson's background, and if it is hard to tell so at a glance, his landmark retrospective revels in what the artist loves to do. The very qualities that have gradually built a body of work worthy of veneration could hardly, and more ironically, mock the system in which it flourishes more. It's enough to make you think that art may not help the world so much by revealing mystic truths as by just being silly. But, of course, it's not. That's the point.

Benjamin Patterson's restaging of Nam June Paik's "One for Violin," 1962, at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.Benjamin Patterson and Peter Kotik, SEM-Ensemble performing at the Akademie der Bildenden Kunst, Vienna, June 1992. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Wolfgang Traeger.

Benjamin Patterson's restaging of Nam June Paik's "One for Violin," 1962, at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.Benjamin Patterson and Peter Kotik, SEM-Ensemble performing at the Akademie der Bildenden Kunst, Vienna, June 1992. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Wolfgang Traeger.