The night before the first debate in Denver, I ran into Kevin Madden, the 40-year-old, square-jawed senior aide to GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney, in the lobby of the Denver Renaissance Hotel. Madden is about as disciplined and professional as they come in political communications. But when I saw him that night, he was tired, and despite his poker face, it showed. He’d been on the road with Romney almost every day for the previous three months, and it was clear he missed his wife and three sons. Romney’s flagging campaign wasn’t helping things.

I had just arrived from the airport, and as we talked over our late dinner in the middle of the lounge, a young child on the other side of the expansive lobby started crying. Madden glanced over. “I’d give just about anything to have some screaming kids right now,” he said.

Others on the Romney campaign were milling about as well. They seemed to be in good spirits, despite Romney’s bad poll numbers. Sen. Rob Portman (R-Ohio), senior Romney adviser Stuart Stevens and Austin Barbour, Stevens’ deputy, walked over to Madden and me. Barbour was quietly confident that Romney would perform well in the debate the next evening. Portman, who played President Barack Obama in debate preparation with Romney, told a story about the time he saw President George W. Bush take a nasty spill while mountain-biking at his ranch in Texas, but then rebuke aides who rushed to his side and tried to put his bike on the back of a truck. Bush got back on the bike and finished the ride. Perhaps it was an analogy for what he hoped Romney would do the next night.

Yet despite the modest optimism, there was no mistaking it: Romney had endured a terrible September. The Republican convention did little for him at the end of August. The Democrats then had had a successful convention that gave Obama momentum. And Romney’s bungled response to the attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi, Libya on the anniversary of Sept. 11 began a terrible two-week stretch. Five days after the Benghazi attack, Politico dropped a story about dysfunctional campaign infighting. And the day after that, the video of Romney’s “47 percent” remarks hit the news cycle.

Romney’s propensity for gaffes did not seem lost on his campaign staff. At a Romney fundraiser at the Ritz-Carlton in Sarasota, Fla. on Sept. 20, I was sitting in the back of the ballroom as Ronna Romney, the ex-wife of Mitt’s older brother Scott Romney, spoke to a crowd of about 250 people. I noticed that a Romney campaign official did not seem to be paying attention to Ronna’s remarks, and mentioned it. The aide leaned over and said, “Maybe she’s more on message.”

The debates presented an opportunity for Romney to get back on track. After months of wall-to-wall coverage of every move and utterance the candidates had made, the 90-minute verbal sparring sessions slowed down the news cycle, as both

candidates went underground for several days before each match up.

Romney and his team saw the debates as a potential game-changer and prepared accordingly. The GOP nominee tended to do his preparation in a variety of places — campaign headquarters in Boston; a Marriott in Burlington, Mass., about 30 minutes from downtown Boston — and then he liked to show up early to the city where each debate was being held and do prep there for at least a day.

“It didn’t occur to anybody not to take it seriously,” Romney senior adviser Ron Kaufman told me. “Romney’s a person who takes things seriously. It was important. He knew the audience was tens of millions of people who were going to be interested in the race. Why wouldn’t you take it seriously?”

Right after Labor Day weekend in early September, a full month before the first debate, Romney spent two days in Windsor, Vt. for his first immersive debate prep experience. I learned later that longtime Romney adviser Beth Myers, who oversaw the process for selecting his running mate, had been the loudest voice insisting that Romney block out large chunks of time to get ready for the three debates. Myers, one Romney adviser said, was also the one responsible for choosing Portman as the one to play Obama in prep sessions.

President Obama is shown here about to speak at a fundraiser for Senator Barbara Boxer and the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee in 2010. (MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images)

Obama took a different approach to the debates than Romney, going to more remote locations and then flying into the debate city the day of the showdown. Obama spent two days at the Westin Lake Las Vegas Resort in Nevada before the first debate in Denver, two full days at the Kingsmill Resort in Williamsburg, Va., ahead of the second debate on Long Island, and then two days at Camp David ahead of the final debate in Boca Raton, Fla.

Obama, whose busy schedule as president made it difficult enough to set aside large chunks of time to prepare, didn’t seem as keen as Romney on cramming either. He decided to skip an afternoon session ahead of the first debate to go see the Hoover Dam. And when a supporter asked how the prep was going, Obama joked, “It’s a drag. They’re making me do my homework.”

‘WE’VE UNSTUCK THE SON OF A BITCH’

A few days before the first debate, I sat in a Chicago high rise across from Jim Messina, Obama’s campaign manager, in his office. I asked him if he was relaxed. The storyline at that point had become, essentially, “How in the world did Obama manage to end up in such a good position, despite a bad economy and some very unpopular signature legislative accomplishments?” Obama was up in the national polls, and looked like he might be on the verge of running away with Ohio. One Republican in Ohio told me Romney was “stuck in the mud” there.

Messina insisted that he wasn’t taking it easy, however, and said that he expected things “to tighten.” And Ben LaBolt, the national spokesman for the Obama campaign, told me he was bracing himself for a Romney surge. Yet Messina insisted that even if Romney made a move, the Democrats were outpacing the Republicans in early voting and their ground game. Their grassroots organization, he said, would carry them through the last month.

“I think Citizens United has so changed the air wars that at the end, people are going to pick up their TVs and throw it out of their living rooms, metaphorically, and look at their family and friends, and neighbors, and say, ‘What do I do here?’ And that’s the moment that we have a huge advantage,” he said.

Messina noted that he was going to “work every day for the next 40 days to win this election.” But then, for a moment, he permitted himself to savor the near future after an Obama win. He would, he said, “take a deep breath and go watch the University of Montana beat Montana State.” Messina is a University of Montana alum.

The intrastate grudge match is scheduled for Saturday, Nov. 17, 11 days after the election.

“Baucus and I are going. We already have our seats,” Messina said, referring to his old boss, Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.).

“We’re going to go and have a really big Moose Drool Beer,” he said.

All that faded, of course, the day after the first debate. In the spin room afterwards, on the campus of the University of Denver, Romney aides had a pretty easy night of it. They fielded questions of course, but didn’t need to say much. Romney had clearly won, and worse, Obama had contributed greatly to his own loss. The president had been so passive that Saturday Night Live later mocked him, suggesting that Obama had even let Romney claim that he killed Osama bin Laden.

The press devoured Obama’s advisers when they finally entered the room after a more than 10-minute delay. David Axelrod and David Plouffe, in particular, the twin swamis of the Obama high command, were swarmed by packs of reporters. The only time I had seen anyone under more pressure in a spin room the entire election was when Texas Gov. Rick Perry faced reporters himself after the GOP primary debate outside Detroit, in November 2011, to try to explain himself after his horrifying “oops” moment.

Back at the Renaissance hotel, the mood was ecstatic. Madden and fellow Romney advisers Stuart Stevens, Eric Fehrnstrom, Ron Kaufman, Ben Ginsberg and others mingled with a group of campaign staff and reporters. They were careful not to be too jubilant. But there were a lot of smiles.

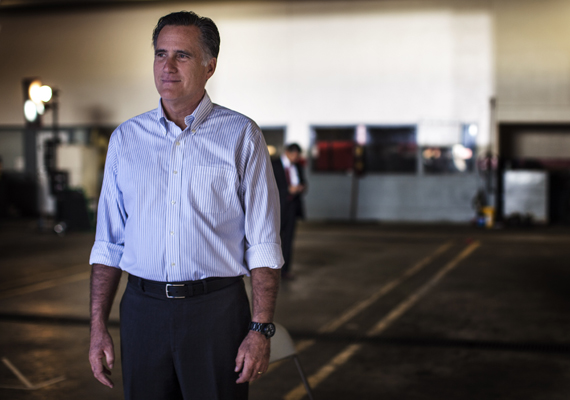

Governor Romney waits to deliver a speech at a rally in Hobbs, N.M. (Photo by Melina Mara/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

The next morning, I left the Renaissance and walked down the street about three blocks — rolling my suitcase behind me through hotel parking lots and gravelly, trash-strewn bus stops — to the Holiday Inn where Obama had spent the night. A bus was standing by to carry me and other reporters to a nearby rally, and within an hour we were deposited in a park on the banks of Sloan’s Lake, about 10 feet away from performing artist Will.i.am, who was trying to warm up a few thousand Obama supporters.

The crowd, shivering in the cold, was still shell-shocked from the president’s woeful performance the previous night, and Will.i.am told a somber story about the need to stay positive. Nobody on the Obama campaign — not Messina or anyone else — was pondering which beer they might be drinking on Nov. 7.

The Ohio Republican who had complained of Romney being “stuck” before the debate, told me several days after the debate that things had changed.

“We’ve unstuck the son of a bitch and we’re back on the highway,” he said.

OBAMA STOPS THE BLEEDING

Ahead of the second presidential debate, a Romney campaign aide told me that they had built a replica of the set on which Romney and Obama would face off. This is something both Republicans and Democrats have done for many presidential cycles. An official involved in Obama’s debate prep, told me they did the same this year, as they had in 2008, and said that Democrats have done this going back to Bill Clinton’s first campaign in 1992.

A realistic town hall set, the Obama adviser said, “makes a huge difference for the mock debates.”

“Obviously, you want the candidates to know how close their opponent will be, what the personal dynamic will be. On the town hall the movements are important,” the Obama adviser said. “Serious business! And ludicrous at the same time.”

Pictures of the Romney mock set up, in a ballroom at the Marriott in Burlington, Massachusetts, revealed a striking level of detail. Romney staff built three-tier risers in a circle, put red hotel ballroom chairs on them, placed a moderator’s table at one end and two director-style chairs at the other end for the candidates, and draped what looked to be about 10-foot-high blue curtains around the entire thing.

They set up TV-style lights on scaffolding that shined on Romney and Portman, who stood in for Obama, from three angles. There was a digital timer with red lights on the ground in front of the moderator’s desk. Perhaps most important, the Romney campaign set up video cameras exactly where they would be during the real town hall, so Romney could practice with that in mind.

It wasn’t perfectly identical to the real thing. The debate set at Hofstra University had six risers, compared to the Romney’s campaign’s eight. But it was very close.

It allowed Romney and Portman to field questions while walking around and facing questioners sitting in the audience. The Romney campaign prepared their candidate for what to do if Obama invaded his personal space, like Al Gore did to George W. Bush in 2000. They were most concerned that Romney not be caught in a situation where he was seated on his chair and Obama was walking toward him or hovering over him, launching verbal grenades. If seated, and Obama approached, Romney was told, make sure to stand up to him, literally.

It turned out Romney was more than prepared for physical confrontation. In fact, he came close to overdoing it when he essentially told Obama to sit down. All the adrenaline seemed to get the better of him when he tried to talk over the moderator, CNN’s Candy Crowley. The atmosphere was so charged that Romney’s son, Tagg, famously joked a day later that he wanted to “take a swing” at Obama (a remark he apologized to the president for personally after the third debate).

After the town hall, an aide to Romney who saw him immediately after he came off stage said Romney was “furious” with Crowley for speaking for the president when Romney was quizzing him on Benghazi, allowing the president to avoid answering why there were conflicting explanations from the administration. But, the aide said, Romney cooled off after he decided that the impact of the debate had been limited.

The first debate had fundamentally altered the contest between Romney and Obama, because Romney, in the flesh, was not the malevolent creature that the Obama campaign had been telling voters about since the summer. The second debate, coming 13 days after the first (with a vice presidential debate in between), stanched the bleeding for Obama. He was forceful and in command.

But the polls continued to show Romney gaining ground. The Republican’s momentum had slowed, but not stopped.

WHO’S BLUFFING?

The spin room at the final debate, at Lynn University, was a circus. It was so packed with reporters and campaign officials that it was hard to move around. And there were sideshows such as actor Pauly Shore, who somehow got a press pass so that he could walk around and promote a new show, and Triumph the Insult Comic Dog, a hand puppet who at one point ran past me chasing someone.

A few factors guaranteed that the third debate would be less consequential than the first two. The topic was foreign policy, a subject that is complicated and does not move many undecided voters. The San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals were playing Game 7 of the National League Championship Series. Monday Night Football was also on. And it was the third and last debate — by now, the novelty of seeing the candidates face each other had worn off. Viewership ended up being around 59 million, compared to 65 million for the second debate and 70 million for the first.

Each side recognized that how they framed the night would be as important as what the two candidates said during the debate, so there were more big names in the spin room beforehand than usual. Messina came through and talked to the press. Madden, who was usually around before debates, stood a few feet away holding court with his own group of reporters. Democratic National Committee press staffers kept a steady stream of surrogates coming through, including Sen. John Kerry (D-Mass.) and Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden, the vice president’s son.

I asked Messina if he thought the debates had been unusually significant. I prefaced my question by noting, lightheartedly, that the pre-debate spin room was a more “contemplative” place, hoping to prod him away from talking points.

“Do you need a hug?” Messina joked, laughing. The crowd of reporters around us also cracked up. But Messina wasn’t about to be distracted from sticking close to his script.

“We’ll have political science write books about it. What I care about is 15 more days to get 270 electoral votes,” Messina said.

There were some Obama surrogates who don’t spend their lives sparring with political reporters, however, who were a little more frank about the impact of the debates. Michelle Flournoy was undersecretary of defense for policy from 2009 to 2012 and could be secretary of defense if Obama gets a second term. When I asked her for her impression of the debates, she said Obama had been better over the course of all three debates, but admitted, in a nod to the first one in Denver, “Certainly these debates have probably had more impact on this race than has been the case in many previous elections.”

In the era of televised debates, a few stand out. The Kennedy-Nixon debates in 1960 were the first to be shown on TV, and are widely credited for giving the younger, more photogenic Kennedy a big edge. Ronald Reagan’s one 1980 debate with incumbent Jimmy Carter, a week before election day, is thought to have given Reagan a large boost toward victory. And veterans of George W. Bush’s campaign said that after Al Gore sighed his way through the first 2000 debate, that helped Bush overcome a deficit of a few points.

Obama and Romney shake hands at the third and final presidential debate in Boca Raton, Florida. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

If Romney wins on Nov. 6, the 2012 debates will quickly enter that small group of determinative debates.

Much of the talk in the spin room was less about the debate and more about the state of the race. “What do you think?” reporters asked one another over and over, having heard the spin from both sides enough to be able to recite in their sleep. CNN’s Peter Hamby and I compared notes and came to the same conclusion. “It’s a genuine jump ball,” Hamby said. I chatted with National Review’s Robert Costa and BuzzFeed’s Ben Smith. Smith thought Romney had the momentum. Costa mostly agreed, but he insisted that Romney still had an uphill climb.

The spin room was still buzzing an hour after the final debate had ended. And the Obama campaign saw the need to continue spinning the next morning. Axelrod and Messina held a conference call with reporters in which they talked at some length about why they thought Obama had won the debate, and why they were in a good position to win on Nov. 6. Axelrod tried to smack down what he called a “mythology” that states like Florida and Virginia were slipping away from Obama.

As Romney flew west from Florida to Nevada, Madden told reporters on the plane with him that Florida “is like a freight liner,

and once it turns — and I think it’s turned — it’s hard to turn back.”

That night, at a rally with 12,000 people in Colorado at Red Rocks, Romney said the debates had “supercharged” his campaign.

The next day in Reno, he said Obama had been “diminished” over the course of the three weeks.

After the last debate, Obama still held the edge in three key swing states: Wisconsin, Nevada and Ohio. Without one of them, Romney would fail to get the 270 electoral votes necessary to win the election.

But a multitude of signs — Obama’s anxious push to score points in the final debate, Axelrod and Messina’s conference call, a move by the Obama campaign to put out a new 20-page booklet to try to demonstrate an agenda for a second term — pointed to unease in Chicago. Madden called the pamphlet “a glossy panic button.”

Axelrod was clearly piqued by the Romney campaign’s crowing.

“I’m just telling you guys, we know what we know and they know what they know, and I’m confident that we’re going to win this race,” he said. “And we’ll know who’s bluffing and who isn’t in two weeks, and I’m looking forward to it.”

To read more, download our new weekly iPad magazine, Huffington, in the iTunes App store. This story appears in Issue 21, available Friday, November 2.