Great Sino-Japanese Battle at Fenghuangcheng" by Toyohara Kuniteru III, October 1894*

October has traditionally been a month of surprises, and this year is no exception. Unexpectedly, China and Japan now seem headed on a collision course. Tensions are high, and the Japanese military reports that Chinese ships have entered waters near the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, refusing to leave. The Japanese air force has scrambled 54 times against incursions by China into their airspace. Japanese businessmen have returned home from their posts in China, fearing boycotts and violence. Could a dispute over a few tiny islands actually result in war? Bound by treaty to defend Japan, which side would the United States take in a military confrontation?

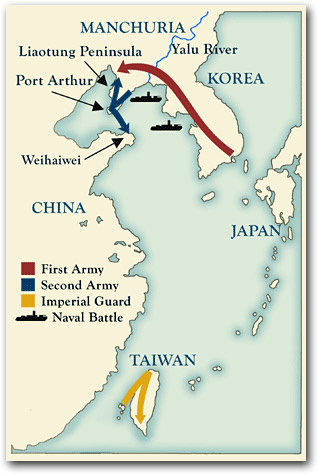

The answer to the first question is yes; China and Japan could clash militarily in order to resolve a border dispute that in many ways is a proxy for the continuing conflict over Taiwan. Both Taiwan and the Senkaku/Daioyu islands were ceded by China after Japan's victory in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894. The Treaty of Shimonoseki also forced China to abandon Korea and pay reparations of something close to four times annual GDP to Japan in silver taels. This war and its aftermath set the stage for Japan's next victory over Russia in 1905 and its subsequent rise in military power, with disastrous results for China that are known to all.

The Sino-Japanese War -- Japanese Lines of Attack 1894/5*

The Sino-Japanese War -- Japanese Lines of Attack 1894/5*

Thinking the unthinkable requires a look back at what China has done in the past. The People's Republic has defended its borders before. Back in 1979, Deng Xiaoping, who had just embarked on his fabled economic reforms, warned President Jimmy Carter that he intended to go to war with Vietnam: 小朋友不聴話, 該打打屁股了。Translation: It's time to smack the bottom of unruly little children. China won. Vietnam withdrew from Cambodia and the Soviet Union, embroiled in Afghanistan, was put on notice. I remember my first visit to China, to Hainan Island in 1979. The entire island, across the Gulf of Tonkin from Vietnam, was crawling with PLA tanks. It was a sight I shall never forget. Deng made a shrewd calculation that he could get away with this show of strength, and some say it was also intended to consolidate his power domestically. The current Chinese leadership could be placing a similar bet.

Both China and Japan face domestic political uncertainty over the next six months, and Japan is still dealing with problems as a result of nuclear accidents post the 3/11 earthquakes and tsunami. The U.S. is also in a state of political flux, and has strong ties to both countries. We have a commercially symbiotic relationship with China. Japan is our most populous ally, but it might be hard to garner support to defend five uninhabited islets and three barren rocks in the East China Sea. Japan is also in a weaker commercial position. Her economy is more dependent on China than the reverse, and recent anti-Japanese sentiment seems likely to result in a .8 percent drop in Japan's GDP this quarter. Military hostilities would further drain a fragile recovery.

China and Japan are the world's second and third largest economies respectively. If they come to blows, the possibilities for geopolitical rifts are far-reaching. The danger lies in a long and unresolved history of enmity, which reached its peak prior to World War II. Even today, in the furthest regions of China, when the Japanese are mentioned, the first response is "Nanjing" referring to the infamous Nanjing massacre which resulted in the horrifying deaths of some 200,000 Chinese. Although numbers lose their meaning at this level of atrocity, more recently, the Cultural Revolution which was a strictly internal political struggle, resulted in the death of 20-30 million Chinese citizens. While many Chinese seem to have forgiven their government, they have yet to forgive the Japanese who bring them goods, services, technology, and 1.5 million jobs. Economic integration has succeeded but reconciliation has failed.

The Japanese and the Americans also fought a bitter war, which only ended when nuclear weapons were used by the United States, inflicting some 200,000 casualties. Yet today, Japan and the U.S. have formed a firm and reliable alliance which seems to survive turnstile prime ministers. However, the difference in outcomes might be due less to cultural factors and more to geography -- we live far away from each other. The history of East Asia over the past 150 years has been the story of the geopolitical competition between China and Japan as they faced Western powers, as they modernized and jockeyed for position and survival.

Many Westerners assume that early modern China was supine, and was not a rising industrial power. That is not true, although this was a view widely caricatured by the Japanese propagandists who often portrayed themselves as Western vis a vis the Chinese. Meiji Japan and Qing China created rival naval shipyards and competed for global trade. From 1926-1936, during the worldwide Depression, Chinese industrial production doubled. In many ways, the conflict between China and Japan over the past century is rooted in commercial competition with each other and the West.

Throughout its modern history, as China sank into civil war or political chaos, the Japanese became the go-to enemy. Lest anyone think that anti-Japanese sentiment in China is new or solely confined to the events of World War II, there were nine major boycotts of Japanese products between 1908 and 1932 which resulted in both economic losses and loss of life. The Japanese saw Manchuria as a kind of free trade zone they could fortify and defend. Trade between the two nations was itself strong, and China exported about 25 percent of its goods to Japan. Had the two greatest Asian nations created common cause against the Western powers, history might have been different. In fact, that was the idea behind the much-maligned Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.

I strongly believe that China and Japan remain at loggerheads because, perhaps in an Asian way, they refuse to directly confront ugly memories with a view towards reconciliation rather than blame. More importantly, I do not believe that either side has their history quite right. The events that led to the Japanese invasion and occupation of China are not well understood in either country. Until an accurate and fair account emerges about what happened in the Interwar years between Japan and China, when the U.S. as a rising power increasingly focused on the war in Europe, this critical bilateral relationship remains the greatest risk to world peace in this, the Pacific Century. We may rail against the apparent failings of the European Union, but as the Nobel Committee reminded us when they awarded the EU the Peace Prize, there have been no major wars between its member countries for the longest period in European history.

In Asia, there is no union of any kind -- neither monetary or political union, nor any institution with enforcement and arbitration powers that yokes together Asia's greatest nations in common purpose. ASEAN +3 is just a start. In what seems to me proof that they are not ready to be a superpower, the China's highest finance officials refused to attend the World Bank meetings in Tokyo last month -- simply because they were held in Japan. What is behind this not-ready-for primetime behavior? The Senkaku/Daioyu island conflict is not about five tiny islands, any more than a row over who does the dishes is the core concern of an unhappy marriage. This conflict masks a deeper rift, and as in any kind of therapy, it is necessary to go back and understand the causes.

So could China and Japan come to blows? Could a fishing boat incident result in armed conflict that then draws the United States into the fray? I find this hard to imagine. But in a world that faces so many challenges to its continued growth, if it becomes difficult to invite the Japanese and the Chinese to the same parties, the rest of the world will suffer. They need to begin true efforts as reconciliation, even if their current leaders were born after the events of World War II. Eisuke Sakakibara, as finance minister of Japan, once suggested a common currency for Asia and was strongly rebuffed by Larry Summers. It was during the Asian Financial Crisis, before Wall Street got its comeuppance. Time perhaps, to reconsider an Asian Monetary Fund, or Asian Union?

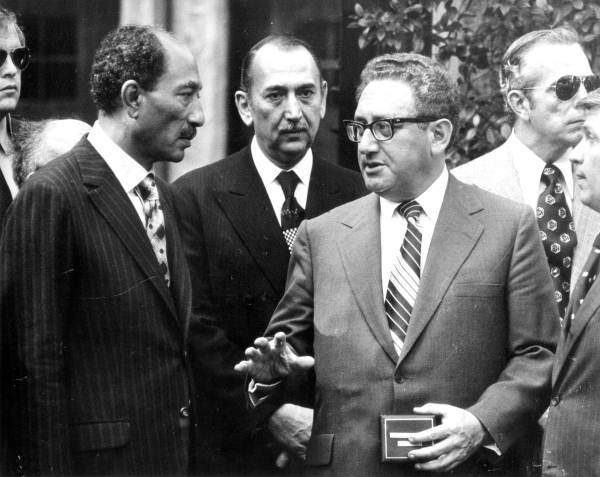

Courage is necessary to look back through history and come up with a new conclusion, and a new paradigm. Recently I read a book published by Yale Press, The Limits of Détente which caused me to rethink the recent history of the Middle East. I had always placidly assumed that détente was better than war, but in his compelling narrative of the Arab-Israeli conflict between 1969-1974, Craig Daigle makes the case that détente between the U.S. and the Soviet Union actually created the conditions under which Anwar Sadat was forced to take military action against Israel. The conflict escalated to the point that U.S. forces were put on worldwide alert in October 1973.

"... it is impossible to ignore that the October War was in large part a product of Soviet-American relations and decision-making during the previous four and a half years and thus was a consequence of détente. After pleading with Soviet and American leaders for three years to abandon the "no war, no peace" situation that had solidified in the Middle East as a result of détente, Sadat felt compelled to launch an attack against Israel to move the superpowers off their frozen positions. In taking his country to war however and creating a crisis of detente, there can be no question that Sadat's strategy proved successful. Although he had suffered a near catastrophic defeat and the near destruction of the Egyptian Third Army, he accomplished in three weeks what he had been unable to accomplish in three years: moving the Arab-Israeli crisis to the forefront of Americas foreign policy and beginning the process that would lead to the return of the Sinai Peninsula to Egyptian hands."

Anwar Sadat and Kissinger

Of course, the person at the center of this drama was Henry Kissinger, who was also the architect of Nixon's China policy. Détente with the Soviet Union ended when the USSR invaded Afghanistan. President Ronald Reagan decided to play it tough, and in one of history's great surprises, the Soviet Union folded. The conflict between China and Japan requires more than détente, or a simple relaxation of tensions. It requires a new agreement. The news, denied by both sides, that the U.S. and Iran are planning direct talks after the presidential election has been called the latest October surprise, and it is a very good one. Let's hope that we don't have a negative surprise in the East China Sea. That three men don't make a tiger once again.

*"Throwing Off Asia II" by John W. Dower -- Chapter Three, "'Old China, New Japan'" Massachusetts Institute of Technology © 2008 Visualizing Cultures

Lyric Hughes Hale is a writer and contributor to a range of publications, including the Financial Times, Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Current History and Institutional Investor.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog. What's Next? Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy by David Hale and Lyric Hale is available now from Yale University Press.

This post originally appeared at the Yale Books blog. What's Next? Unconventional Wisdom on the Future of the World Economy by David Hale and Lyric Hale is available now from Yale University Press.