Bacho, Tanzania - It's a typical story: Americans go to Africa for safari. They find that the television images of big-eyed children with protruding ribs, crusted with dirt and biting flies, are real. Then they see there is a lot more to the story, that the people are real too.

Women from the village

My friend Marianne had always dreamed of going to Africa, since as a little girl she watched "Born Free" wide-eyed in wonder over the majestic animals roaming through rolling plains and resting under umbrella acacia trees. She and her husband Don, both poorly paid high school teachers in California, pinched every dollar to raise their four children and help them get through college. Then, having married young enough to have half a life still ahead of them, they looked ahead to Marianne's upcoming 50th birthday.

"It's a milestone," Don told Marianne. "What do you want?"

"I want to go to Africa," she replied simply. "The real Africa."

So they went. Marianne got to see her lions, cheetahs, elephants, giraffes, hippopotami, rhinoceroses, and zebras. They even saw pink flamingos. They chose Tanzania in East Africa, where they could see more animals per square kilometer in Tarangire, Lake Manyara, and Ngorongoro Crater than anywhere else on earth. They rode around in open-top Land Rovers just like all the other tourists, oohing and ahhing and snapping photographs. But they knew 97% of residents of this undulating land could not afford the bus ride to and entrance fees into the parks to see their own nation's wildlife; that 80% eked out less than $2/day doing subsistence farming.

"Let's go see how the other 97% lives," Marianne said to Don. She had found in her Lonely Planet book a small tour company, Kahembe Cultural Tours, that promised authentic experiences with remote local tribes. They would stay in a village, converse through a translator, share local food, even sleep on the floor of a mud hut.

"You are crazy," owner Joas Kahembe's friends told him when he first launched his business in 1996. "What are they going to do? What will they eat? And why in god's name would they sleep on the floor?"

Joas, who had run a successful coffee export business and studied international trade in Finland, had come to believe that his country's rich ancient culture would be lost if not shared with the world. He had also learned the quirkiness of mzungus, Europeans and Americans. He just laughed. "You would be surprised what white people will do," he told his friends. And he was right.

Joas Kahembe, tour guide and project manager, in Babati.

By the time Marianne and Don came along in 2007, Joas had led several groups through the Bacho village area southwest of Arusha. They would launch from the small town of Babati, in his modest Kahembe Guest House with oft-functioning electricity and a good home-cooked breakfast, and venture to villages as remote as his rickety Subaru can take them. For tourists as adventurous as Marianne and Don, they could move right in to a one-room mud-brick house and sleep on the floor with the eleven other family members.

To me, frankly, climbing Africa's highest peak, the nearby Mt Kilimanjaro, sounds easier. At least then you have time to acclimate gradually to the elevation, and plenty of local sherpas will lug your stuff.

But my unspoiled friends popped their malaria pills, boiled water from the nearby stream, dug their right hands into the shared family pot and tried maize porridge, myriad versions of cooked bananas and beans, and--only for the most special occasions--a goat roasted whole with fruit protruding from its mouth, chunks with the fur still lining the greasy meat gobbled with glee.

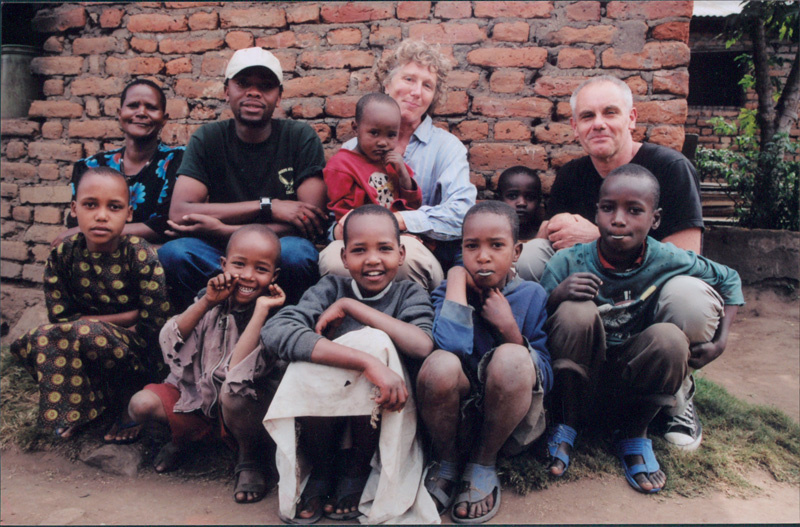

Marianne and Don Kent-Stoll with the Kwaslema family in Bacho, Tanzania

Just five days with the Kwaslema family turned them into lifelong friends, in Marianne and Don's view. But something else happened that would change the course of everyone's lives. It began with a latrine.

Adjacent to the village primary school, a rickety system of old tree branches strewn with worn animal skins balanced precariously over a pit latrine. It was unsanitary even by the poorest standards; so bad the Tanzanian government had threatened to close down Ufani Primary School if the villagers could not raise funds to build proper facilities for their students. Marianne and Don, who already had dedicated their whole lives to the education of their own children and students, could not leave Bacho without doing something to help.

The old school latrine

The school that Karimu rebuilt, with a new 6-stall latrine with clean water for hand-washing

Between them they had $300 in their sweat-dampened wallets. They had thought to buy souvenirs for folks back in California; instead, they bought building materials for a brand new 6-stall pit latrine. The villagers set to work.

When the time came to make their way back to Arusha to lodge overnight before their 3 flights home, the 2 American tourists also promised their new friends that they would help rebuild Ufani school.

"We will spend the next year raising money in the U.S.," Marianne promised. "And we will send you the money so that you can repair your school."

"That's all well and good," the head teacher, Paul Yoronimo, responded. "But we want you to come back."

"It costs so much to fly here," Don protested. "What you could do with that money . . ."

"Yes, we understand. But we want you," Paul insisted, looking them in the eye and taking Don's hand. Don began to cry. And that was the first of many crying jags to come.

That year, Marianne and Don taught themselves how to incorporate a legal nonprofit, calling it Karimu ("Generous") International Help Foundation. They had no idea how really to change outcomes for their new friends 9,729 miles away, or how to operate a charitable foundation. What they did know was that they cared, a lot, and wanted to help.

They hosted fundraisers at friends' homes, recruited volunteers to cooked an African dinner at the local church hall, and raised $34,000 to rebuild the primary school. Joas the tour guide became their local project manager, overseeing purchase of materials and hiring of local fundis, builders. The villagers set to work and by the time the next summer rolled around, their friends returned, multiplied. Marianne and Don raised separate funds for airfare and brought 27 volunteers from their high school and hometown. This time, everyone cried.

It's been five years now, and Karimu has returned each summer to work alongside the families, teachers, and students of Bacho to transform their community. So far, they've built 9 pit latrines, 6 classrooms, 3 teachers' offices and 6 teacher houses; refurbished 1 primary school; funded special education programming and teacher training; contributed books and bed nets and a microscope; and launched health training for midwives. This summer, they have seeded the community's first microfinance program for businesses run by 15 HIV+ members who came together to form a credit group.

2 Karimu-sponsored health initiatives of the Bacho area: KAMM maternal/women & children's education program, led by Veronika Mosha (back row, far left); and new HIV+ microcredit group overseen by Dr. Wilson Bilalama (second row, far left); in front of the 4-room health clinic that serves 25,000 people in 5 villages

This August they will return with another 25 volunteers. They will brick, stucco, and paint new teachers' houses, and work as aids in the special education, midwife training, and health education programs. They aare also currently fundraising to bring clean-burning Aprovecho "rocket" cookstoves to as many of the 193 local households as they possibly can.

Traveling through Tanzania this summer, I get a backstage peek at the village community just before the Karimu volunteers arrive for their fifth annual visit. Having flown into Kilimanjaro International Airport too late last night even to see the continent's tallest mountain, I have slept briefly in the city of Arusha before jumping in a jeep to head 3 hours to Babati, transfer to Joas Kahembe's intrepid Suburu, and bounce our way another 3 hours to Bacho. Good news to report back to California: The Japanese government has financed a brand-new paved road through the first half of the journey, and lumbering, slow work is being done to pave the road all the way to Bacho. "One cannot love one's car and still be able to drive these roads," Joas laughs as we jolt from rut to rut, dust exploding just outside our closed windows.

A recent community survey reports that this community lives on less than $1/day, and that a major factor exacerbating poverty here is the "very rural location . . . [that] adds to the voicelessness and a perceived inability to influence their lives" (Julian Page, Livingstone Tanzania Trust). Not only will a road bring access into the village to deliver medicines and a variety of food and goods, and enable farmers access to bigger markets for their produce, it could also pave the way for the #1 wish of everyone I ask: electricity.

I arrive with a certain amount of skepticism. I have seen a lot of Americans, myself included, throw money and hope at causes far beyond our capacity to change. I have heard one of my own snarky sons proclaim that Karimu--like my own nonprofit organization--exists for the sole purpose of stroking our egos.

School kids of Bacho Village

The students have all gathered in their uniforms, along with their teachers and families. They know I have only a couple of days to spend among them, and that I want to talk with all age levels, from fresh little optimists to crusty elder sages. As I make my rounds, talking with various groups in the very classrooms that Karimu built, I ask bluntly: What do you think about this group who keep coming back to meddle in your business?

Marianne and Don, teaching English to young Bedouins in Oman and unable to join me in Bacho, have emphasized that they want me to get to know the community "behind our backs," ask how people feel about the project and what they most need right now. "Find out what they really think when we're not around," Marianne suggests.

What I find is a very small group in transition: The elementary and high school students benefiting from rebuilt classrooms and improved test scores envision a future with computers, good jobs, and wealth. Still, not one of them plans to study farther away than Arusha, and no one dreams of the world beyond northern Tanzania.

Their parents want the world for them, however; they fervently channel all their ambitions onto their sons and daughters. They swell with pride over the glass windows in the school buildings, perhaps more than they do over the fact that their primary school graduates have risen to #4 in the nation on their exit exams. The foremost need the families express is for a bridge to be built between the two halves of Bacho, so that everyone can remain connected during the harsh rains of winter.

"We call them [Marianne and Don] mother and father," says Paulo, a mustached man in a brown shirt with a bolt of tribal fabric tossed over his shoulder. "May God speed their journey safely so they can return to us." Many of the adults echo this passive attitude of sending messages of gratitude and humbly requesting what's next in their efforts to end poverty and educate their children. Yet I have to wonder, with no television or computers, how could these adults envision any other way to build their own future, without the help of Karimu?

Parents and village leaders voice their views on education and technology in the village

A few visionaries have. An older woman in a blue and orange headscarf, Mwanahamisi, tells us she has helped begin a health education initiative on malaria and maternal and childcare. Yasinta, a young mother in a white headscarf, notes that the students used to have to "study under a tree" and now enjoy "buildings so strong that even an earthquake could not destroy them," and cites the impact as "happiness inside our children" as well as increased high-school matriculation. Marseli, who taught himself and others mixed-use farming with rotating crops and varied livestock, calls for farm machinery (e.g., to grind maize), electricity, and computer courses for all.

And the teachers long for a different sort of bridge: They crave connection to other educators in their country and around the world via electricity and Internet access. Because Karimu has funded continuing education coursework for them (through Open University), they have learned what they are missing far beyond the coffee and banana plants cascading down the verdant hills of Bacho. "We need tools to help us learn about the whole world," says Paul.

Teachers of Ufani primary school

It shouldn't surprise me that nearly everyone cites the friendship with Marianne, Don, and the Karimu volunteers as foremost in value. "If we had to choose" between financial support and friendship, teacher Edward Kessy says, "we could not do it. Of course, you have to build the physical [infrastructure] first, but we can see that to have both tools and friendship, that will be the best."

"Education is the key to life," Bertha Sumari nods. "This is the way to advance society."

Daniel Amma sees changes taking place here, but slowly, slowly. "This is Africa," he laughs. "Gradually the number of students attending secondary school will increase, and then the number attending college will increase. We must wait until our students move all the way through the system for the big changes to occur in society," in perhaps 10 years' time.

In the meantime, what the tourists of Karimu take away from Bacho may be more than what they leave behind. "The volunteers have learned kindness first," suggests Paul. "What they find here are loving people who live in a peaceful place. They learn how to wear our kanga [skirt]. And they now try to compare our traditional dance to their American way."

"They are our ambassadors, to spread our way of life," says a man named Peter in a green knit hat. "They take on our traditional ways of life, and we learn about America. They come with their children, and in the end, we become one society, Ufani and California. We are very happy when they come."

As my visit progresses, I get to taste fresh tilapia from the community pond, with rice soaked in coconut milk. I chat with many students from both schools, and sit for hours with teachers in their on-campus houses. The local dance troupe tries to teach me an Iraqw tribal dance, and Joas and his wife take me to a Tanzanian wedding send-off party and talk me into trying the furry roast goat.

When the time comes to leave the village, it's been far too short and superficial--not on their part, but on mine. Typical impatient American, I have rushed in for a few days, expecting to learn all about a community whose history dates back to the earliest era of human existence, in the "Cradle of Humankind" where the first upright humans left footprints 3.6 million years ago.

If the volunteers of Karimu receive (as I suspect they will) as warm and genuine a welcome, as open an extension of friendship, then it's easy to see how these tourists have transformed into development workers. New school buildings and teacher houses, health and special education programs, bed nets and cookstoves, all show the physical evidence of care from Karimu. Perhaps the advanced education of students, improved healthcare and hygiene of families, and boosted profits from microcredit group work, have already begun to shift the impetus for change into the hands of the villagers who live here year-round. For the tourists who come just once per summer, they will celebrate the end of this year's efforts with a trip to the local dance club and safari drives in the national parks. Then they will return to their life of comfort in the U.S.

However, along with their photographs, tribal dance steps, and Swahili vocabulary, they also will bring back the knowledge that with just a few dollars and a couple of weeks' time, they have truly made leaps forward in being the change they wish to see in the world.

Award-winning documentary film on the work of Karimu Foundation

Disclosure: Because the founders have worked at our sons' school, we have not funded Karimu through the Skees Family Foundation. Our stories of Karimu are among a series on social-change organizations (some beyond our portfolio) that we believe have respectful programs with pragmatic impact.

Karimu International Help Foundation, a private operating foundation, runs on a shoestring, collecting donations each year and promptly dispensing them into buildings and programs that last all year. They continue to ask, through their research and conversations, "How can we help?" They have chosen to focus on a small geographic area, hoping to model a holistic partnership of care.

If you would like to learn more about Karimu, check out their website, read Don's blog about their adventures abroad, or donate directly to send cookstoves and health/education materials to Bacho this August.