Secretary of State John Kerry's trip to Colombia last week builds on President Obama's renewed efforts to deepen relations with Latin America but hidden in his security and trade agenda lie many unanswered questions for U.S. exporters around the pitfalls of starting a business in the midst of an on-going conflict.

Secretary of State John Kerry's trip to Colombia last week builds on President Obama's renewed efforts to deepen relations with Latin America but hidden in his security and trade agenda lie many unanswered questions for U.S. exporters around the pitfalls of starting a business in the midst of an on-going conflict.

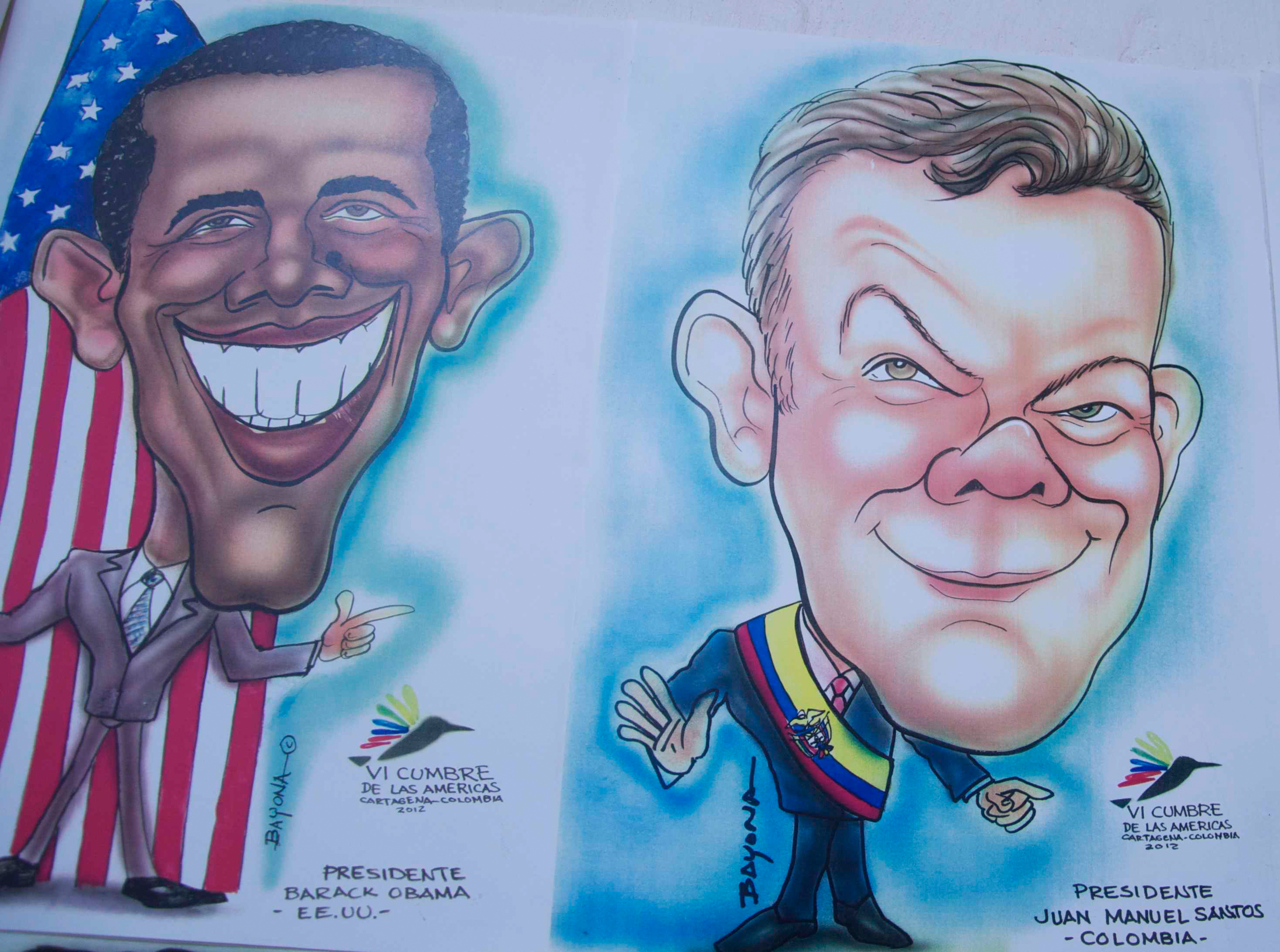

As Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos moves towards elections in May next year, his major headache centers on pulling in billion dollar investments whilst at the same time resolving land issues at the core of Colombia's half century internal conflict. Herein lies the danger for U.S. investors and exporters.

Since the early 2000s, Colombia has been a lone U.S. ally in the region with billions of U.S. taxpayer dollars of mostly military aid flowing in to support counter-narcotic and counter-insurgency efforts. Now with increased security levels and peace talks underway in Cuba, Washington and Bogota are touting this South American nation as a leading destination for U.S. businesses.

In May last year, the U.S.-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (CTPA) entered into force, in a bid to enhance economic growth in both countries and create thousands of jobs in the process. In an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that ran in April 2011, then chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, John Kerry argued that the Colombian free trade agreement was essentially a bill to create American jobs. "Each day we fail to act," he wrote, "costs American jobs and sales -- and sends them elsewhere."

This free-trade agreement immediately eliminated tariffs on 80 percent of U.S. consumer and industrial exports and currently the International Trade Commission estimates a $1.1 billion expansion of U.S. exports to Colombia.

In fact, forty percent of all U.S. exports now go to Latin America, for the first time in decades rivaling US economic activity in Europe and Asia.

At the same time, exports of U.S. goods to Colombia have barely moved at all since May last year rising marginally from $1361.4 million USD to $1406.8 million USD.

In early 2011, Colombian President Santos both vowed to turn the high plains (east of Colombia) into an agricultural powerhouse and to drive forward the mining engines of the country in the northern coal zones.

In 2012, he even tried to ease the strict rules on the sale of smallholding land on the grounds that they blocked economic development. But the reform was struck down last year as unconstitutional resulting in a loss of more than $1 billion in promised agribusiness investments.

As part of the peace talks in Havana in May this year, the FARC and the government came to a tacit agreement on land issues to redistribute farmland and develop infrastructure. However, even this land is plagued by legal irregularities. Colombia's Federation of Cattle Ranchers went so far as writing a letter to the chief government negotiator Humberto de la Calle warning that FARC and other illegal armed groups are concentrating land ownership.

Professor Roberto Vidal, a legal expert from the private Javeriana University in Bogota, tells me that his main worry is that "The agreement reached on land in Havana still leaves 70 percent of the country remains open to big agro-industrial development at the expense of small-holding farmers."

President Santos' delicate balancing act between big investors and small farmers blew up in his face in May this year when an investigation by the international development organization Oxfam showed up a potential illegal land grab by the Minneapolis-based food giant Cargill Inc. in the eastern Vichada department of Colombia. Cargill allegedly set up front companies so that they could sidestep the tight limits on landownership.

Santos and his new Agricultural Minister Francisco Estupiñan have tried to dismiss this political hot potato as they maintain that there's enough land for both peasants displaced by guerrilla and paramilitary violence and companies wanting to get in on the land action linked to the boom in soy beans, ethanol and palm oil production.

At the same time, paramilitaries, known locally as criminal bands or "Bacrim," continue to rise in numbers since a failed demobilization process took place between 2005 and 2006. According to another Colombian university professor, who wished to remain anonymous, "The paramilitaries still control the majority of Incoder's (the state's land authority) offices in the countryside either directly or through local pawns in the mayor's and governor's offices of rural Colombia."

Beyond the more recent Cargill case, Colombia's hinterland is littered with unresolved land disputes like the case of Bellacruz in the north of Colombia. In the mid-'90s, the family of ex-Minister Carlos Alberto Marulanda used paramilitaries to side-step legal ownership problems and during the following two decades property names and owners (local and foreign) have come and gone until April this year when Incoder declared that the land would be repossessed by the State and given to local farmers. Germán Efromovich, a Colombian magnate and owner of the national airline company Avianca, maintains that he bought the land in good faith and has title papers to prove his claim. Since May, the case remains locked in the courts.

In an off-the-record interview with a Colombian land expert at the beginning of August, I was told "Santos will do whatever he can now to sidestep land distribution cases like Cargill and Bellacruz by marginalizing Incoder and re-emphasizing his 2009-10 campaign promises to champion large-scale investments by the agro-industry. Incoder and the Victims Law are simply 'necessary distractions' to pave the way to his holy grail of peace based on big money and a rapid-fire transformation of Colombia's heartland."

In fact, President Santos and his Minister for Finance and Public Administration Mauricio Cardenas slashed the 2014 budget for Incoder to $85 million USD harking back to the times of ex-President Uribe (2002 to 2010) whose primary goal was to weaken the institution.

His reasons for doing this are likely linked to the stark reality that the Colombian state doesn't have the financial muscle to reform its land issues by itself and needs some level of local and foreign big agro-industry investments. It's precisely this sort of investment that USAID Administrator Rajiv Shah pointed to when he met with President Santos in April this year saying, "Mainly we are discussing the opportunity to bring private investment to the rural areas of Colombia."

While the Colombian government struggles to even map out what land can or can't be categorized as belonging to the state, the overall picture doesn't provide much legal security nor clear property rights for a US company to buy land in Colombia and running operations like coal mining to harvesting palm oil remain risky at best.