Eduardo Porter has published an article in the New York Times titled, "A Universal Basic Income Is a Poor Tool to Fight Poverty" It is not the first article to make such a claim, and it won't be the last, but all such articles tend to share one thing in common -- the outright omission of all evidence to the contrary, and a gross manipulation of facts to build an argument out of straw.

In the case of Eduardo's piece he offers three false premises: 1) Basic income is too expensive and could only be funded by defunding everything else; 2) Basic income will provide a disincentive to work but toil is for our own good; and 3) The freedom basic income provides as cash is damaging to people who would be better off with paternalistic programs that limit their choices and treat them like children. Being that none of these things are true, it's sufficient to say his idea of methodically taking something apart is sorely lacking.

Too Expensive?

As I've already covered in a prior article addressing the affordability of basic income, the estimated cost in the US to provide all citizens over 18 with $12,000 per year and under 18 with $4,000 per year would be around $1.5 trillion in additional revenue. This price tag does not touch Medicare or Medicaid or education or defense. It does touch Social Security but in a way that leaves all recipients better off.

Basically, there's no reason whatsoever that a large portion of Social Security can't be distributed in the form of basic income instead, with Social Security itself still existing as a top-up for seniors and those with disabilities. If you're receiving $1,500, there's no reason that can't be $500 or any other number, on top of a $1,000 floor that every citizen receives. It is absolutely false to say this can't be done in a way that leaves everyone currently receiving benefits better off, and still reduces government administration costs in the process.

The question is then does replacing welfare benefits leave those receiving such benefits worse off? Is this as Porter suggests the redistribution of wealth upwards? I've written about this before as well. An example would be a single mother of two receiving $45,000 in Medicaid, child care, housing, food, and cash assistance getting $12,000 in basic income instead. In that case, yes, she and her kids would indeed be worse off, but again, Medicaid is not part of the deal, and neither is child care. Basic income would replace housing, food, and cash assistance totaling $20,000 with a basic income of $12,000 for her and $4,000 for each kid, so $20,000. She is no worse off at all. In fact, because she no longer has to ever jump through another hoop for any of those things again, and unlike before, can earn any amount on top of her basic income without it being taken away from her like welfare would, she is far better off.

So if one cares to dig into the details, which I do recommend we do, it's patently false to claim that a universal basic income by design will leave people worse off by leaving us no choice but to replace all of government with cash. Any intelligently designed program would do no such thing, and realistically there would be no politically achievable way of doing otherwise, because neither the extreme right nor left is going to get everything it wants.

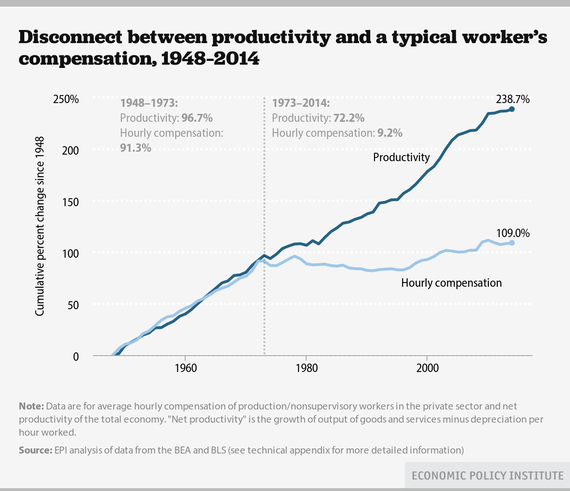

As for where the $1.5 trillion comes from, that answer is simple. It comes from the raises no one has gotten since productivity decoupled from wages and salaries back around 1973. Basic income belongs to us because it's been effectively stolen from us for decades.

Source: EPI

We are more productive now than ever. We are doing more with less. We are worth more to our companies than ever before. But we aren't being paid for it like we used to as part of the unwritten productivity growth deal. The result is the real upward wealth redistribution that has been occurring for decades, and being squirreled away in places like Panama.

It doesn't even stop there. Our taxes were invested in basic research and development, and the resulting technologies have been eliminating middle-skill jobs for decades, replacing them instead with the many low-skill jobs of today. Effectively, we're like employees getting our salaries garnished to train our machine replacements, with no pension as part of the deal and only worse paying jobs to look forward to if we're lucky. That's not a fair return on our investment. That's getting stabbed in the back.

Meanwhile, spending an additional $1.5 trillion to reduce poverty and inequality would likely save more than that by preventing the costs of not reducing them, costs imposed by health outcomes and crime rates that wouldn't exist to the same degree with universal basic income in place.

To look at all of this and ask where the money will come from is a joke of the highest order. The money is there, it's just massively maldistributed after decades of upward redistribution. Universal basic income is a real way to correct such massive levels of inequality.

Disincentive to Work?

The second argument Eduardo makes is that a basic income would sap the desire to work, and because "work remains an important social, psychological and economic anchor," basic income would be a bad idea. Although unmentioned by Eduardo, some strong evidence to the contrary was mentioned in another New York Times article late last year.

Abhijit Banerjee, a director of the Poverty Action Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, released a paper with three colleagues last week that carefully assessed the effects of seven cash-transfer programs in Mexico, Morocco, Honduras, Nicaragua, the Philippines and Indonesia. It found "no systematic evidence that cash transfer programs discourage work." Still, Professor Banerjee observed, in many countries, "we encounter the idea that handouts will make people lazy."

It's a good article I suggest be read in full. The author went on to explain how cash assistance does not show work disincentive effects, instead providing "very tangible benefits" especially for kids who go on to see improved longevity of life, educational outcomes, health, and incomes in adulthood. The author even concludes with a response to Paul Ryan who last year wished to move people from cash assistance to work.

Before the United States goes down that road again, however, it might make sense to reassess the strength of the underlying argument: that poor people will never act responsibly, get a job and stay in a family unless they are thrown into the swimming pool and left to struggle with little support from the rest of us.

So the author warns the reader that we should look at the evidence before thinking people won't find work unless forced to. I agree. That's exactly what we should do. What does strike me as odd is how the author is the same Eduardo Porter.

So, on the one hand, Eduardo believes basic income won't work because work is so important for us to keep doing and we'll choose not to work if work becomes fully voluntary. On the other hand he himself is familiar with the evidence that giving people cash does not reduce the amount of work we do, and does in fact have many positive effects. Even odder, Eduardo's article about welfare even makes the point that people continue to work despite the high marginal tax rates that welfare imposes by being removed with work. Universal basic income doesn't even have that problem because it's never reduced with any amount of earned income above it.

This is where it becomes clear that universal basic income is an idea judged by many not logically or scientifically, but emotionally. This is likely why Eduardo himself can make the case against those perpetuating the myth of welfare's "corrupting influence" regarding work disincentives in one article, and then in another about universal basic income, practically forget everything he knows is true in order to argue against giving people sufficient money to live without conditions aka basic income.

Be wary of any article against basic income that doesn't include any supporting evidence. Applicable experiments have been done. We have studied the work disincentive effects in the US and in Canada in the 1970s where the results were quite interesting. Fully universal basic incomes have been tested in Namibia and India, where the results of both were more work, not less. The charity Give Directly has given basic incomes to people in Uganda and Kenya, where the results in both locations were more work, not less. Unconditional cash transfers are being used more frequently all over the world entirely because of their successes, and in places like Liberia and Lebanon where they ended up being like basic incomes, they too show more work, not less.

Perhaps most interesting of all the applicable evidence of cash without strings is the seemingly universal shift from typical wage labor to more self-employment and unpaid work. This in no way points toward people doing nothing. This is also why basic income is not at all an idea about paying people to do nothing, but instead about paying people to do anything. There is so much work being done right now that is not seen or recognized as work, but is. And there is so much work people want to be doing on their own volition that they are prevented from doing in a system that requires they spend their hours working for someone else just to survive.

Look at the evidence. Always look at the evidence. If you do that, here's what the evidence is saying in a nutshell: in a world where all resources are locked up and money is the only key, a minimum amount of money does not prevent work, but enables it. No one can pull themselves up by their own bootstraps if they have no boots. The only way to make that possible is to make sure everyone starts with at the very least, a pair of boots with straps. That's universal basic income. It's universal bootstraps. It's the idea that in a globalized economy requiring less and less work of humans to meet the demand for everyone's basic needs, no one should start with bare feet.

And this brings us to the final straw...

Not Paternalistic Enough?

Eduardo Porter argues that a housing voucher is better than cash, because parents would be forced to use a housing voucher on housing and thus would be more likely to move to a better neighborhood, whereas they would be less likely to use cash on housing and therefore less likely to use cash to move into a better neighborhood. He is absolutely mistaken.

First, when asked to agree or disagree with the statement "cash payments increase the welfare of recipients to a greater degree than do transfers-in-kind of equal cash value," 84 percent of economists agreed. The greater value of cash to not cash is one of those few things almost all economists agree upon. It's also why sometimes food stamps are sold for less than face value, so that people can gain the freedom to make their own choices on how to use it.

Second, the reality of housing vouchers is nothing at all like Eduardo thinks it is, possibly because he's never actually experienced it. The reality is that vouchers are only accepted by those who choose to accept them, and those who choose to accept them tend to not be located in better neighborhoods. Chicago's "supervoucher" program provides an illustrative example, by being a program specifically designed to enable those in poor neighborhoods to move to wealthy neighborhoods.

After driving around different neighborhoods, she and her children decided Lincoln Park was their top choice. But Weaver, who is African-American, quickly realized that even with access to CHA's new supervouchers, finding affordable housing in a prime Chicago neighborhood wasn't easy. "We had a few places that said, 'Yes, we love her, we want to do this!' " Weaver recalls. "Then when they found out I had a voucher they would say no." Eventually Weaver told her real estate agent to alert people up front that she had a voucher and see if they were still willing to show her the apartment. "I would say out of ten at least seven canceled."

After searching for almost two years, and after scores of application fees, Weaver finally gave up. In the end she described the experience as "one of the most disgusting and deplorable experiences" she's ever had. The reality of housing vouchers is that few accept them, even despite any laws created to prevent that.

Yvette Jones has been a real estate broker for 22 years and works with many voucher holders. She says that out of ten listing agents or landlords she might reach out to, "maybe one" will be open to leasing the unit to a Section 8 client, supervoucher or not. Chicago is one of the few places in the country that bars discrimination based on a renter's source of income, including vouchers. The law is supposed to protect voucher holders like Weaver, but it's rarely enforced, and when it is, the penalty for landlords is only $500.

But the reality of housing vouchers is even worse than all of that, because to have a housing voucher you have to be deemed worthy of said voucher. This is where the grand flaw of means-tested assistance rears its ugly head. The truth is that 76 percent of those who qualify for housing assistance don't get it. Meanwhile those who do get it go through long waiting lists and the assistance is temporary in nature based on income.

Now compare all of this to cash. Whereas only one in four deemed worthy for assistance gets it in a means-tested system full of government bureaucrats and all of their hoops, four in four get basic income because there are no bureaucrats or hoops. There are even states like Wyoming where 1 in 100 living under the federal poverty line get TANF, whereas 100 in 100 would get basic income. The real effect of targeted benefits is that more people aren't helped than helped, and that help is always temporary. Basic income in contrast never goes away with any amount of income earned on top of it, and because it's universal and cash, it can truly be used anywhere by everyone.

In fact, when recipients of cash dividends in North Carolina were faced with an extra $4,000 per year without conditions, moving to nicer neighborhoods is exactly what some of them did. Should this really be surprising?

That people can use their basic income anywhere in any way they deem fit is its great strength. Cash can be used in an infinite number of creative ways, including the creation of innovative new businesses and inventions. It can be used at the consumer end of those as well. It can be put into savings. It can be used to pay down debts. And yes it can even be used to buy drugs and alcohol. But is that how it actually gets used? A meta-analysis of 19 studies and 13 interventions found that not a single randomized trial found a significant increase in alcohol and tobacco purchases as an effect of cash without conditions.

On the other hand, those same people in North Carolina given cash dividends saw decreases in alcohol consumption. That shouldn't be surprising either, but unfortunately it is because most people don't understand what actually drives addictions and that's impoverished environments. Watch this video by Kurzgesagt and read about "Rat Park." I've also written about this topic before as well. Want to reduce drug use? Eliminate poverty and reduce inequality.

We should all be fed up with non-evidence based thinking. I certainly am. I'm fed up with people writing for well-respected outlets like the New York Times who choose to ignore evidence because it doesn't suit their preconceived notions of how the world works. I'm fed up with people with positions "up on high" looking down at everyone else and telling them they know better who needs assistance and who doesn't, and how that assistance should be provided and when that assistance should be taken away. I'm fed up with the idea that anyone must prove their right to live to anyone at all.

Is universal basic income a poor tool to fight poverty? No. It's the best tool to fight poverty, because poverty inside a monetary system is quite simply a lack of money. Poverty is the inability to purchase food and housing. It's the inability to afford a new outfit for that job interview, or transport to the job if given the job. It's the inability to afford schooling. It's the inability to focus on anything except for where enough dollars are going to come from to live day by day. Poverty is a lack of resources.

To fight poverty, we must simply abolish it. And to abolish it, we must get over the many scientifically unfounded mental barriers that have always prevented us from doing it to this day, mainly the notion that one must work for one's daily bread.

We must flip this notion on its head and finally understand it's the bread that makes anyone able to do any work in the first place.

---