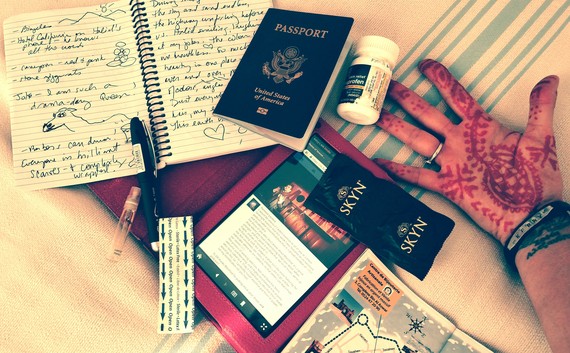

Essentials, practical and purposeful, for your journey:

Band-Aids:

I used to carry Band-Aids in all my purses and pockets because I used to cut my arms with whatever was sharp and at hand. An Xacto in my wallet. A paper clip on a desk. A shard of glass in the gutter. Now my arms, though scarred, are healed since I no longer believe that I deserve pain and shame but am inherently worthy of pleasure and joy. These Band-Aids are strictly for skinned knees (sliding down a rocky cliff in the Atlas Mountains), blistered heels (dancing to the wild drumming and singing of Berber nomads), and a camel-chafed thigh (legs astride the dromedary's wide body for three hours across Saharan dunes in a sandstorm).

One night in the coastal city of Essaouria, a city so drenched in color that when I wandered its maze of streets I felt like the throbbing pulse inside a stained glass heart, I stopped at a café. Gnawa musicians were playing their guitars, drums, and tambourines. Their music is an African blues descended from North African slave songs. One of the drummers, a hip-twenty-something nomad (turban, white robe, and black Chuck Taylors), sat beside me, smiling, and offered me hash.

"No," I said. "But thanks." Moroccan men offered me lots of things (mostly tea and marriage) because I was an American woman traveling alone. I said "No," to most of it.

He looked me over, and then suddenly, grabbed my arm and touched the scars across my wrist with his finger. He nodded, pushed back his robe's sleeve, and turned over his brown arm. His forearm was crisscrossed in scars. "Yes," he said. "Me, too. But now I am okay. You are okay?"

"Yes," I said.

"Good," he said. "We are good."

No Band-Aids necessary. Just healing words.

Ibuprofen:

For hangovers of all kinds. Too much mountain-climbing (to see the waterfall where the men, swimming in the icy pool, unfurled their prayer mats to pray in the shade). Too much sun (from driving across desert roads, my head hanging out the window like a happy dog's, trying to lap up the light). Too much Shisha (smoking a hookah for an hour with my friends in Rabat, the apple tobacco burning under the red coals, smoke ribboning from our nostrils).

But not for a real hangover. Not anymore. Five years sober and I never felt so drunk as I did on too much joy, in my hours of wandering inside a prism (rugs, doors, robes, markets, stalls, tiles) and swallowing the call to prayer, constant because of Ramadan, that filled the streets and sky.

Condoms:

Better safe than syphilis. This was not in anticipation of any traveling promiscuity. I don't sleep around. Which is not to say there's anything wrong with sleeping around if you do it clear-eyed and with deliberate intent, i.e., to revel in the body's shared joy-making. But packing condoms was also a belief in what might be possible. Not just random, hook-up Spring Break sex on the beach, but those kinds of connections that occur because you are in a specific place at a specific time and bump up against a fellow traveler, someone not just sharing, coincidentally, your itinerary for a day or a week, but someone who shares a capacity for joyful vulnerability and risk. I was traveling, in part, to put some distance between myself and T., my miraculous fling of the previous months. We were still friends, but my heart was in carefully guarded pieces, still tied to the hope of him. Was it possible to see beyond him? So this offered a different kind of hope for a different kind of fling.

Anton was sitting in the Jardin Majorelle, a beautiful garden in Marrakech, with his camera perched on his knee, an old Flexaret Automat, the kind that you look down into as if snorkeling across the surface of the earth, or the garden, in this case. He was a professional photographer, and miraculously, also a recovering alcoholic five years sober. We started talking, and he asked to look at my pictures, all two thousand. After an hour of scrolling and pausing, he said, "I feel what you see." It was a perfect day which turned into a perfect night. Crystalline and contained.

Perfume or Cologne:

In the desert, I didn't shower. Too much sand blowing and sticking in my ears and on my neck and somehow inside my bra and underpants. Pointless to try to wash it off because it would just blow back again. So a little jasmine at the collarbone and on the stomach. But perfume everywhere, anyway. Real jasmine and honeysuckle. Cumin and lavender. Olives and figs. Mint and rosemary. And an earthy sweat, as if the tawny dust was seeping through my skin and into my body. The sea was sharp with salt. And the cloudless sky, an endless blue wave, smelled like truth.

Pen, Paper, and Words:

Many pens (they will run out) and a notebook (it will be full and then so, too, will the backs of receipts and the margins of maps and hotel brochures). Writing into the late hours of the night, inside the SUV as it barreled around the mountain cliff edges (fighting off nausea to get the words down), in the orange-walled restaurant lit by candles where I romanced only myself, on the train without air conditioning in 110 degrees, sweat dropping on the pages, smearing ink. So many words in lists, jagged, spontaneous, unformed-- memory's shorthand.

Bicycles.

"Hotel California" on Khalid's phone--he knows all the words!

Red and pink canyons.

Stone ziggurats.

Joke: I am such a drama-dary Queen!

Berbers can drum!

Everyone in brilliant scarves and complexly wrapped.

Watching YouTube music videos with Berber bachelors.

Looking at T's picture on phone while riding camel in the swell of the sand dunes--heartbroken.

So much beauty and over and over, permutations of colors, angles at the sky.

Dust in my hair, my eyes, my mouth. Grit in my teeth. This earth is taking me over.

Grief and longing. Need to write it and write it away.

Map:

To know where I was, where I had come from, and where I was going. Where are the Atlas Mountains in relation to Marrakech? Ouarzazate--the name I could never say with certainty--was exactly where in all that desert topography? How many hours between one stop and another? How many songs would Khalid and I try to sing and dance to while driving? He wanted to listen to my music, so we plugged in the IPod and laughed through Beastie Boys and Foo Fighters and Taylor Swift. He kept replaying Ray LaMontagne's, "Hey, No Pressure," stumbling through the choruses with intensity, trying to form his mouth around the English words: "Anything you want to be you can be, Anything you want your life to mean it can mean."

"You," he said to me once, "you no married? You free? You go where you go?"

"Yes," I said, trailing my hand out the open window through the air, as if trying to catch all of the speeding country in my fingers. "I go where I want to go here. But home? I stay with my children. Love keeps me from moving, moving, moving."

Passport:

Of course, there is customs on entry and departure. But a passport is not merely proof of citizenship or a collection of exotic stamps. Both the stamped and blank pages are space for dreams: where have I been and where do I want to go? Stamps of joy (Bahamas yoga ashram) and stamps of pain (Jamaica, the last trip with my ex-husband who had already moved on to the other woman).

Morocco's stamp was one of hope: do I dare take on this world alone, my single, solo self? This was my first trip after my divorce. I could have chosen some all-inclusive sex camp in Cancun, or a beautiful but "safe" idyll in Tuscany. But I wanted to risk all of me, push the boundaries of what felt comfortable, try to navigate my way through an utterly foreign landscape and language. To say: Yes, I'm scared shitless, but I'm doing it anyway. This is the only itinerary to a Joy-Stamp.

A Whole and Willing Heart:

The henna design on my palm, inscribed by a Berber girl as a "thank you" for taking her family's photographs, is the symbol for an open and full heart. I sit writing this now, three weeks later, at my desk in Pennsylvania, and my palms are still stained with the orange ink, as if I am still holding my heart in my open palm, offering it to the world.

This open heart is the center of wanderlust. Meeting others not with fear or defensiveness, not with assumptions or guidebooks, not with wariness or judgment but with my heart. A friend once said that I wear my heart on my sleeve. It's true. But better that than cuts on my arms. This open, full heart is what led me to the Berber girl's kitchen where she mixed up green henna paste and spent an hour slowly writing a story of hope and love across my hands. Her younger brother fed me bites of pistachio cake and gave me sips of tea while the henna dried. Their father showed me his drawings he made while in prison; they were elaborate, colorful geometric mazes.

"I used to look out the narrow window of my cell at night," he said," and memorize the arrangement of the stars in the sky. Then I would paint that part of the universe. It was how I felt free."

When his daughter brushed off the dried henna from my hands and rubbed a garlic paste into my own stained maze, she smiled. "Beautiful!" she said, proud of her handiwork. "Beautiful! I think you will find a husband now! If that is what your heart wants."

Courage:

Courage to pack my inside self, the self that is both damaged and healed. I packed along a photo of a friend, Terence Leclere, in his moment of discovering his purpose. He is performing for Mortified (listen here: http://mortified.prx.org/2016/05/61-how-not-to-masturbate-and-other-hollow-victories/), a podcast and performance dedicated to telling stories of adolescent silliness and shame; his story was about the angst of teenage masturbation. When the podcast went live, he sent it to me, a little mortified that something so personal (even though he told the story in front of a live audience) was now more public.

"What you're doing is courageous," I said. "Being open as an artist, you end up going where you're needed. Your job is to be vulnerable to tell that story, whatever it is."

I can see his courage in that photograph as he stands on the stage, speaking a truth that might seem on the surface embarrassing (after all, how many of us are willing to talk about our own masturbation history), but under the embarrassment, is the story of connection and longing for shared experience. That's what his story was about: how, inside our solitary hearts, we all share in each other's shame and pleasure, pain and joy. His story is my story is the Gnawa musician's story is the photographer's story is my driver, Khalid's story, is your story.

Also on HuffPost: