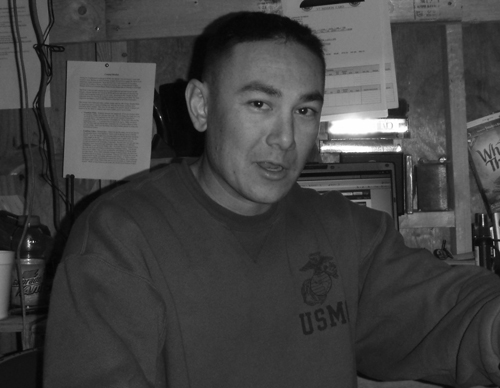

If you had to put a face on the American everyman, Joe Cavins' mug would probably fit the bill. Cavins is a 27-year-old Sergeant in the Marine Corps, working on his third deployment in Iraq. His goal is to accomplish five tours--a plan of attack that is either pathological, maniacal, or the outward manifestation of an unsettled psyche. The thing is, Cavins is about the most stable guy you'd ever want to meet.

He stands about 5-feet-8 and probably weighs a buck-sixty. He's got light brown hair and brown eyes that adorn a typically American countenance. He's the product of a typically American small town--Newport, in Monroe County, Michigan--which lies about 40 minutes south of Detroit (the all-American town that Americans love to denigrate). He left that place for the most typical of American reasons: a girl.

In 2004, Cavins and his then-girlfriend, Kelly--the Jack and Diane of a strange new century--didn't know what the hell they wanted to do with their lives (he was working construction, she was bartending) or where they wanted to go. But they knew one thing for certain: they didn't want any more of Newport or small town America. A simple plan was hatched. Joe would join the military and fate would decide their next exotic home. He went away to boot camp at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot in South Carolina, in the spring of 2004.

Boot camp was as tough as boot camp is supposed to be and Cavins--who's a hard guy not to like--got through it just fine. The only hiccup came near the end of the 13-week stretch, when he got a letter from Kelly. She was pregnant. And they both knew, according to the math, that Cavins wasn't the father. It turns out she'd had a one-night stand with her previous boyfriend--a passing fling with heavy repercussions. She kept the baby but not the previous boyfriend ... or the new one.

Though they split before he left boot camp (a hellishly bad time for a heart-rending separation debacle) the two are still best friends, Cavins says, and they talk every week. In the meantime, he's gone on to do three tours of duty in Iraq. His most current assignment--on a Police Transition Team in the small Anbar Province town of Haditha--will end in January 2009. After that, he'll be back overseas as soon as possible.

It's not the exotic lure of faraway lands that appeals to Cavins, nor even the idea of living in a culture so foreign it doesn't recognize toilet paper. It's the relaxed nature of combat duty. If there's one thing that Cavins digs about his four years in the service--to boil it down to the very solid core of the dregs of the issue--it's the fact he's not had to stomach a single room inspection. Which is a window onto the mind of everyman Joe Grunt.

In three tours (the most recent has been dull and quiet) Cavins has been "blown up" (hit by IEDs) nine times. He's watched several buddies die and been the spiritual leaning-post of several others who've quietly unwound under the pressures of imminent death and hostility. On February 13, 2007, Cavins was in a Fallujah unit hit so many times it was shut down. He says:

There's a road called Lincoln and it used to be AO [area of operation] Riley. It was on the north side--north of MSR mobile--and when 1/7 [First Marines, Seventh Battalion] RiPped [Relief In Place] with 2/7 they had like a week-long gap when nobody patrolled that road; they couldn't get anybody to go up there to do it. Two-seven pretty much said, We've got all these small towns, we got a couple big ops going on, we're not f---ing around with that road. So they pushed it to us.

Our platoon was gonna take it--four sections, six hours a day, four patrols. Well nobody in our platoon had ever been up there, except me and my section leader, Sergeant Arnold. He volunteered us to go first. We got out there at 5:30 in the morning and by 4:00 o'clock in the afternoon our platoon was mission incapable. We didn't have enough trucks and we had too many guys down in different sections from concussions and medevacs, to keep on with the mission.

A rear-truck got blown up first and our truck turned around and we got blown up. An EOD [Explosive Ordnance Demolition] team came up to clear the IED--what they do is a post-blast to find out what blew us up--and they got blown up on the way, coming through Karma. So our other section came out to relieve us. They were just gonna sit on the site. EOD came up and told them, It was 200-pounds of this, blah, blah, blah. EOD went back down the road and our section guys were like, F--- it, we'll just take the rest of your shift. Then they got blown up.

My buddies Mike Weimet and Stone both got medevaced. So then we had to go back out again to help them cordon the area. So we went back out, Medevaced those two guys and three local nationals--because when my buddy's truck got hit he was knocked unconscious and ran off the road and hit a car. So they medevaced them, we went back out, we cordoned the area, and they had to send a wrecker up because the truck was just f---ed. Well, the Motor T [Motor Transportation] got blown up on the way.

Then EOD came back and they got blown up again. So then we were sitting there with them while they go the truck hooked up. They had four trucks down to three and as we were escorting them down the road they got blown up again. So we had to stop, hook up a tow bar to that truck and start towing it--and then we got blown up again. Finally, when we got back to OP [Outpost] Viking, they sent our other section out, Rebel. They were out for like 45-minutes and got blown up again. I think it was like nine or 11 IEDs that day.

Given his choice--sitting on a Southern California base, in an artificially spruce world where bedding has to be board tight and a wrinkled shirt will cost you recreation time ... or serving in a place where a determined enemy is intent on blowing you up--Cavins will take the latter. Pathological, maniacal or plain unsettled, the thinking is quintessential grunt logic. A hard look at the numbers makes the issue more transparent.

Divide the number of Corps casualties, over five years, by the hundreds of thousands of Marines that have served in theater--the number isn't great. Then look at the chances of getting your balls busted by a gung-ho stateside Staff Sergeant, who's got nothing better to do, and who's got a Second Lieutenant breathing down his neck every minute because he's taking heat off his newly betrothed and he's never truly lived with a woman before; he's on the verge of going nuts and about the only thing that makes sense to him is leaning on his lazy-ass Staff NCO to whip his guys into shape since there's a war going on in the Middle East. The chances of that--ball-breaking, soul crushing skull-drudgery that means nothing in terms of the big picture--are relatively high.

At least in Iraq, whether people back home understand it or not, Cavins is doing something. He's making a difference, amid a Herculean society-building experiment in a land that's been victimized--practically traumatized--by war and heavy-handed, repressive authoritarian rule for ... eons. And it doesn't matter a damn if his boots are shined in the process, or not. It doesn't matter what time he gets up in the morning, so long as his job gets done, and he's got his head out of his ass whenever he leaves the safety of the COP (Combat Outpost).

And as far as COP Haditha is concerned, Cavins leaves a lot. He's part of a 12-man squad that's been attached to India Company (a part of the 3/7 Marines deployed in Haditha since August 2008), which is training local police. The team is called a Police Transition Team (PTT ... known as a pit team among the Marines) and it is part of the Corps' guerrilla wars strategy; Vietnam had military advisors who worked in the same capacity.

The pit teams emerged sometime around 2006 as part of the sage strategy introduced under the guidance of American General David Petraeus (much of the military's surge, in fact, wasn't about straight number enhancement, but dozens of minor strategic alterations). Clear, hold, build has been a mantra of the U.S. military brass the past few years and Iraq is deep into the third stage. Part of that involves increasingly heavy use of pit advisors and Military Transition Teams (small units that embed with the Iraqi Army and counsel and advise its soldiers on effective strategy and leadership).

Cavins works with Staff Sergeant Mayers and Sergeant Peña--who work under team leader Captain Scott Newton--to bring to the police force in Haditha the knowledge and ability to police their own city, without American support. The investigators they're working with, the pit team says, don't need much training. They were investigators under Saddam, they're educated and proficient, and in fact--according to some--could rival American detectives in basic investigation. They're suffering in the realm of procedure, however, and in finances.

They're still working through the process of paperwork, and especially in sharing information (in both directions) with their provincial superiors in the town of Ramadi. The greatest obstacle to effective police work in Iraq, the pit team says, one that might be insurmountable, is money. The detectives don't have patrol units or radios. Until three months ago, they didn't even have filing cabinets. They're still lacking simple folders, just to archive their cases. Regardless, Haditha's creative and determined detective corps has forged ahead and made reasonable progress. The conventional Iraqi Police (IP), meanwhile, have achieved security and stability in town and in the region.

The evolution has been startling, in Cavins' eyes. From a 2007 deployment where he was getting blown up on a weekly basis, to this most recent, where the most serious injury he's sustained has been a paper cut, while training the IPs on the dull and endless paperwork that attends their jobs. Each of the men on the pit team has a different task, and Cavins drew procedure. That means a lot of thankless and boring writing.

Staff Sergeant Mayers, a ten-year vet who grew up in Singapore and Las Vegas, is in charge of administration. He helps the IPs bridge the gap between Haditha and Ramadi, trying to get money, supplies and information flowing between the two cities--a novel concept in post-Saddam Iraq. For a generation of authoritarian rule, the locals didn't have to report too much to provincial. Orders and supplies came down from province (in unilateral fashion) with the regularity of flooding on the old Euphrates. Wheat seed arrived in the fall and supplies filtered in whenever provincial prefects decided they were needed. The idea of the locals planning their own budget and sending in requests for money is a new one in Iraq.

The idea of corruption isn't. In fact, corruption has flourished under the unique dichotomy of insurgency-born martial law, and democracy. As a quick look at a newspaper in any First World, democratic capital will spell out, governmental corruption isn't unique to Iraq. The exacerbating factor is that in the third world the crooks running the government don't seem to have the brains, manners or subtlety to conceal their greed and graft. Many in the civilian population and local government consider Baghdad's cabal of leaders a band of thieves. And the thought isn't reserved exclusively for the capital. The ruling tribe in Haditha, the Jughafi, holds the top two security posts in town--the heads of the IP and the Provisional Security Force--as well as the mayor's office; and it is popularly believed to be Mammon's own crucible of wayward and covetous hands.

Graft and corruption are rumored to be rampant. Which creates a pickle of a situation for the dozen men on the straight-thinking, rule of law pit team. Who polices the police? The Iraqi civilians believe the U.S. bears the responsibility (many here see the Americans as omnipotent saviors with the power to decide who survives and who suffers). The Marines, meanwhile, are continually more hamstrung by bilateral pacts and agreements demarcating their increasingly restricted freedoms and their looming departure date. As stipulated by the SOFA agreement, the Marines have to give local authorities 72-hour's notice when they want to leave the COP (which is but one small absurdity, among a laundry list of them, in an uncharted, unprecedented experiment in forced nation building).

Officially, Cavins and the pit team are impressed with the progress in Haditha's security and are happy to have met their goals for the deployment. Unofficially, they're thankful to be leaving. Dealing with the strange parameters here (asked to help an underfunded police force achieve the impossible--while handcuffed by bi-national agreements) and corruption so rampant it seems institutional, all of which has been carried out in an atmosphere where a grisly death at the far end of a sniper's hollow pointed intention is not only a possibility but a likelihood, the seven-month tour has been frustrating.

Privately, members of the pit team confide the fear that all their work (and, more importantly, their buddy's deaths) could be for naught. If the U.S. pulls out too early (and the SOFA-defined pullout of 2012 is probably too early), long-simmering grudges could easily throw the country back into civil war. And even if that doesn't happen, another hazard lingers--those heroic and brave Iraqi security figures that fought off Al Quaeda and brought stability to Iraq (men who now have small armies of police at their command) could grab for power and turn their civil security forces into militias.

Cavins tries not to think too much about it; he doesn't get paid to think. He goes to the police station when he needs to, keeps alert and does his job. I'm not that smart, he says in a typically self-abnegating tone, when asked about the big picture and hard answers to seemingly insurmountable problems. And really, as aw shucks humble as he comes across, everyman Joe has learned--like all the Marines at COP Haditha--to live the serenity prayer.

The fact is, when the shooting stopped a year ago, the Marines ceased being a truly dynamic force of change. Since then there's been thankless tedium (which is exaggerated by the fact the American media has forgotten Iraq) and a lot of learning to know the difference. The whole thing, the Marines have come to accept--the future of Iraq, and of the Middle East, and by reflection their own sense of achievement--is a crap-shoot and way out of their hands. Direction-changing policy is made at a level so high they can't see that far above them, and, more importantly, when it comes right down to it, the whole shooting match depends on the Iraqis. How bad do they want this strange Western notion of democracy and some semblance of self-control?

The Marines have accompanied them about as far as they can go. Now they're feeling like a parent with a toddler on a bicycle. The training wheels have to come off at some point. And glory or stitches, it's all on the kid after that.

For more observations from Iraq, go to http://sdliddick1.shutterfly.com/