Hampton Sides has written one hell of an Arctic adventure story. In the Kingdom of Ice is the tale of Lieutenant George Washington De Long and his crew aboard the USS Jeannette who, in 1879, attempted to find the North Pole through the Arctic. Their ship left from San Francisco, backed by a notorious New York playboy and staked to the idea that a warm northern current would take them through the Bering Strait. They hoped to reach what was then thought of as the"Open Polar Sea," warm waters made for easy sailing to Asia.

Things didn't go according to plan.

De Long and his crew spent two years locked in a churning mass of sea ice that pushed their increasingly crumbling vessel further into frozen ocean. It was a disaster that killed any hope for an expedient current, the Open Polar Sea, and (SPOILER ALERT) a prolonged future for most of the crew and its sled dogs. Sides tells the story through first person accounts from De Long, ship engineer George Melville (distant relation of Herman), and De Long's wife Emma, who wrote the lieutenant heartbreaking letters throughout the Jeannette's journey.

The story is riveting, a non-fiction page-turner on the level of Devil in the White City and Lost City of Z, and when I read it ravenously on a red eye flight from Anchorage to Atlanta I couldn't help but wonder what it had to teach us about the current Arctic crisis. When I talked with Sides after I returned, and he told me the story didn't end in the 19th century, I was thrilled.

Sides told me that the meticulous records De Long and his crew took throughout their time in the Arctic are now being used by Old Weather, a group of citizen scientists who are working the with National Archives to digitize and analyze the Jeannette's log books.

The story of how the log books survived is nearly as compelling as the story of the Jeannette itself. The massive volumes had to be hauled with Herculean effort through the ice and tundra by the starving crew, then carried through Siberia to St. Petersburg and finally by ship to Washington D.C., where they gathered dust for a century.

Sides was astonished when he picked them up.

"I found about these log books by virtue, really, of sitting down at the National Archives and requesting everything they had on the Jeanette," Sides said. "They wheeled these massive books out on a cart and I didn't really know what they were at first, just that they were really heavy, some of them folio-sized, just massive volumes, you know, and I started thinking, 'How did these get here?' And then I thought, 'Why did these get here?'

"Most of these volumes are truly just log books, just measurements of things in ledgers--specific gravity, salinity, water temperature, Barometric pressure readings taken hourly, a lot of stuff I don't really understand or care about as a writer. I looked at all of them and I thought, 'Wow. That was a lot of work that was probably useless.'

"So it was with great surprise and a sense of satisfaction to learn that NOAA and Kevin Wood and his group at Old Weather are using them on their research."

Wood and Old Weather are digitizing log books and journals from the Age of Exploration to find out what they can tell us about how the world -- in this case, the Arctic -- has changed in the past 150 years. And they want to see what these changes can tell us about what's happening to our climate.

What they've been able to see through De Long and his crew's data is scientific proof of just how massive the sea ice loss has been over the past century and a half, something environmentalists have known in theory for years. Now they have primary documentation.

"The value of a single ship's observations is limited," Wood wrote in an email. "Though it does give us a good sense of what the state of the was like at a particular time and place in the past. If it's very different from today, that is a clue to what the scale of change and variability could reasonably be like."

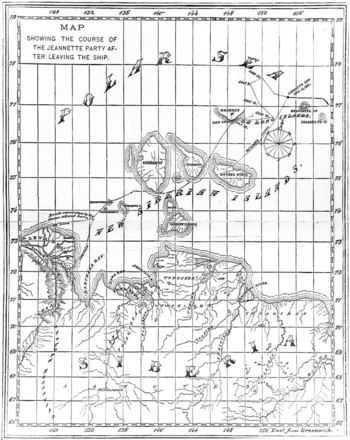

On September 9, 1879 the Jeannette became trapped in sea ice 7-15 feet thick near Herald Island in the Chukchi Sea.

"This area is often ice-free now," Wood said.

He sent a satellite view of the area from a recent day in July, and you can see that it looks chilly, but not deathly.

"This is a month before the date of ice minimum nowadays" Wood wrote,"so I expect there will be far less ice to see on Sept 9, 2014."

Being a scientist, Wood takes a cautious approach to his description of what's happening in the Arctic, careful not to put a dramatic spin on it. Sides takes a more narrative approach.

"The crazy irony is that the Jeannette was designed to test the theory of the Open Polar Sea," he said, "They set out North to find it and didn't, but now, the climate folks are telling us that there will be an open polar sea in some summer soon. There's a deep irony that this mythic thing that's been talked for centuries and centuries might actually happen now."

The irony will be a killer, not only for the indigenous communities who live in the Arctic, the polar bears, walruses, narwhals, and snowy owls who call it home, but the rest of us around the world too. Less sea ice means more climate disruption globally -- more super storms, more droughts, more resource-based conflict. The ice also reflects the suns rays, as opposed to an open sea which absorbs it. Less ice means a warmer Arctic and a warmer climate, which of course means even less sea ice at a faster rate.

"The Arctic explorers, especially the ones who kept going back, were entranced by it, and what they wrote about the ice in particular was poetically and beautifully," Sides said. "Before I wrote this book, I had this idea of the ice as one thing, but it's alive. It's constantly moving and changing, there's pressure ridges, old ice, new ice, fresh water, salt water, all constantly in flux and flow, subject to weather and wind and current. You start to realize it's this living breathing force, not just this slab of stuff that's just sitting there."

It's a living, breathing force that is rapidly dying. De Long and his crew would hardly recognize the Arctic ocean as it exists now. They were a few of the first, and a few of the last, to see the ancient Arctic as it was before fossil fuels. The overwhelming scientific consensus says that the sea ice's disappearance since the Industrial Revolution is due to anthropogenic global warming. The more fossil fuels we burn, the less sea ice we'll have. The late summer sea ice is nearly gone in the Chukchi, and global oil giants like Shell and Gazprom are hoping to exploit its demise. They plan to drill for more of the oil that's causing the sea ice to disappear in the first place. It's enough to make a person renounce the Jeannette's motto: nil desperandum, "never despair.

But there is hope, it will just take some of that 19th century courage to put it in motion.

"De Long took applications from across the country, hundreds if not thousands of people wanted to do go to the Arctic, to see it," Sides said. "There was patriotism, valor, and personal pride in that journey. It seemed like a glorious adventure to huge numbers of people."

The Arctic adventure is different today. We no longer need De Long's 19th century courage of exploration -- we need a 21st century courage of salvation. It's a kind of courage millions of people around the world have already shown by signing up to Save the Arctic. You can join them easily today, and you can also join the Old Weather team as they transcribe data and document events of all sorts found in the logbooks.

"When De Long was making his retreat across the ice and the tundra," Sides said, "he was constantly asking himself, 'Should I be lugging these volumes?' and a lot of his crew were asking that same question. They felt they weren't necessary. But the narrative you hold in your hands with this book was made possible by that decision to keep the books. Who knows what else we can learn from them."