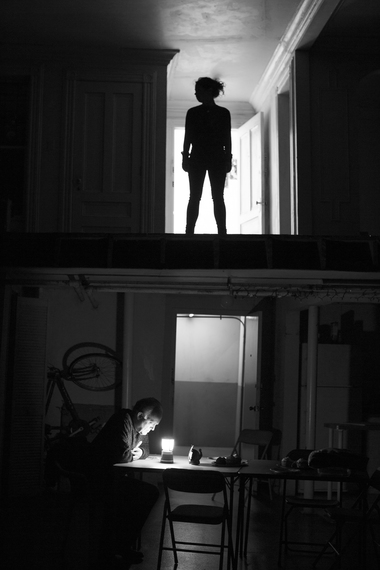

As the lights go up in Stephen Karam's potent new drama, The Humans, we see a balding, sixtyish-year-old man in a baggy beige sweater and loose-fitting jeans standing and holding two plastic grocery bags, sagging, as he stares forlornly into space. It may be the quintessential image of middle America today. The Humans is not an overtly political play. As its title suggests, it is about our enduring existential condition, not about a moment, which is to say that it is a domestic drama in the tradition of Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller, albeit if they had dosed their plays with levity. The Blake family, of whom the forlorn man is the paterfamilias, has gathered for Thanksgiving dinner at the Manhattan Chinatown apartment of its twenty-something younger daughter and her boyfriend, who have just moved in, and in the course of the meal, they proceed to peel away the layers of their sorrow and angst. But if The Humans is more familial than political, it nevertheless demonstrates how that existential condition is expressed in the current moment of discontent that runs through this year's presidential campaign. And that moment contains the nearly inexpressible pain and exhaustion of the beleaguered American middle class.

We all know that something has happened to the middle class in the past two or three decades -- many of us because we are victims of the change and think of our lives as the damage. Post-war America was built on a dream. It was the dream of the middle class, of a good, secure job and a home and a car and higher education for our children and a yearly vacation and the idea that life would get progressively better for us and our offspring.

For nearly a half century in this country, it was a dream fulfilled. But then the dream began to fade. Even before the Great Recession, jobs became less good and less secure for many if not most Americans, and wages stagnated, while expenses soared. By one recent study, over 70% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. "Don't you think it should cost less to be alive?" asks Erik. It could be the question of the age.

Statistically, the middle class is not only being squeezed economically, it is also being squeezed out of existence. According to a Pew Research Center survey last year, the middle class (as defined as a three-person household with an income between $42,000 and $126,000) has been steadily declining since the 1970s, from 61% of the population in 1971 to just under 50% in 2015. There are now fewer Americans (120.8 million) in the middle class, once called the backbone of the nation, than at the economic extremes (121.3 million). And though these Americans may qualify as middle class, they do not live what we once considered a middle-class existence. A 2013 study conducted by USA Today, determined that the typical middle-class life - a $250,000 home, the car, the vacation, the children's education - would cost $130,000. Only one out of eight Americans could afford that, notwithstanding that just about half are middle class. So Erik is right. It should cost less to be alive. Or, put more starkly, most of us cannot really afford to live.

Without ever being didactic about it, The Humans hums with a powerful undercurrent of this economic distress. Erik and Deirdre, his wife and the mother of the Blake clan, go to buy their daughter Brigid a candle as a house-warming gift, only to find it costs $25. A single night of nursing care for Erik's mother, Momo, who is suffering from dementia, they say costs $100. Brigid gets paid off the books so she can continue to collect unemployment, and when she complains about her student debt, and her parents mention the cost of her education, she tells them, "It's not like you gave me any money to help me out" - a line that elicits both laughs and groans from the audience, laughter perhaps to mitigate what the groans signify, which is how much we want to help our children and how difficult it is to do so (and the underlying resentment they feel when we can't). Even the Irish folk song the Blakes sing as a family tradition, "The Parting Glass," begins: "Of all the money that ere I had..." and the first line of its final stanza is, "Oh, if I had money enough to spend and leisure time to sit awhile...." But they don't.

The Blakes are the American middle class personified without being made generic. Erik has worked for 28 years as the head of maintenance at a posh private school in Scranton. Deirdre has worked for 40 years as an office manager. Their older daughter, Aimee, is an attorney at an upper-crust Philadelphia firm. Decades ago, those would have provided the foundation for the good life. But Erik has been fired for a transgression, just before his pension was to kick in, and he hasn't saved any money. Deirdre soldiers on, complaining about being bossed by twenty-five-year-olds who know far less than she, and appreciating full well that in America, age is a curse. And Aimee has just been informed that she isn't on the partner track, which means she will have to find a new job. This is American life in the 2010s, and for most of us, it isn't heading upward. "You can never come back," Momo babbles repeatedly in an unconscious diagnosis of the state of the union.

But it is not just the end of the American middle class as we have known it with which we are face-to-face in The Humans. From a psychological rather than a sociological vantage point, we are face-to-face with something even worse, something even more terrifying and agonizing than the loss of a job or the loss of money. It is the loss of hope. The Humans understands that too. The Blakes try to put on brave masks. They try to hide their disappointments and their despair from one another. After all, it is Thanksgiving, ironic as that is under the circumstances. But the truths leak out gradually. Erik can't sleep and stares vacantly out the window. Aimee suffers from ulcerative colitis. Brigid keeps having to summon the spirit to maintain her dreams of being a musician and composer, even though those dreams have been dashed. And Deirdre has no choice but to pretend she will surmount it all, though the sag in her shoulders, like that in Erik's, tells a different story. The dream is extinguished. And, as Momo repeats, they all know there is no going back. "One day it goes," sighs Eric in the dream's valedictory. "Everything, you know, goes."

In The Humans, the only balm for the condition, though not its antidote, is family and the love that binds it. (The levity in the play comes from the banter of familiarity.) What America cannot achieve in the macro, through some grand national program, individuals must achieve in the micro, through those around them. If there isn't hope anymore, there is still the embrace and forgiveness of those who love and ultimately need us. That is the non-ironical side of Thanksgiving. Hackneyed as it may sound, there is nothing Pollyannish about it in The Humans because playwright Karam doesn't see this familial devotion as a means of salvation, only as a means of survival. You love one another, and you plod on. When Brigid's boyfriend Richard confesses that he was a late bloomer because he suffered from depression, which, he says, runs in his family, Aimee counters that the Blakes don't suffer depression. "We just have a lot of stoic sadness."

And stoic sadness may be the most appropriate response of the middle class to the slings and arrows that beset them. If the play's opening image is a quintessentially modern American one, so too is its closing image. Erik sits alone at the dining table in Brigid and Richard's dingy darkened apartment, quietly weeping - weeping over his errors, his losses, his emptiness, his hopelessness, and, because it is a resonant play, he is weeping for us too. Then he slowly rises, exits, and the door closes behind him, leaving us in darkness as he trudges onward, because that is all any of us can really do now.