In 1995 my family moved to Jerusalem. My mother was pregnant with me at the time. She was there as the New Yorker's Jerusalem correspondent and my father was working as a foreign correspondent for Newsday. They were both covering -- for the most part -- the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As Americans, they were removed in many ways from their work: culturally, linguistically and up until that point, geographically.

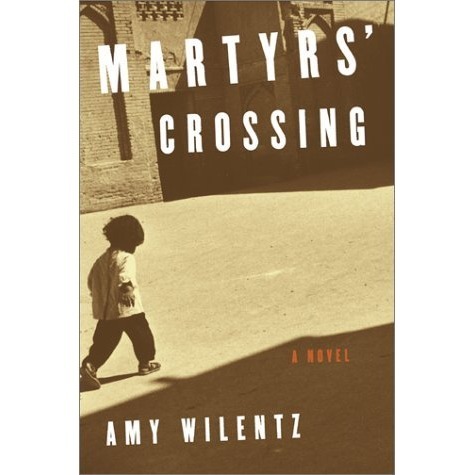

But I imagine that my birth at Hadassah Hospital inextricably linked them to that place in some way. In 2002, my mother published a novel called Martyrs' Crossing about a Palestinian toddler named Ibrahim and his mother, Marina, who are detained as they attempt to pass through a checkpoint into Jerusalem. The boy had a medical emergency that becomes life-threatening because he is unable to access his own doctor in the city. The cover of the book is a photo of a boy walking in golden Middle-Eastern sunlight, his face a silhouette, a tall stone building behind him. He looks just like I did when I was little. He could be me, my mother always said.

But his character isn't me. He occupied a much more dangerous position than I ever have. While my family lived in Jerusalem, New York, or Los Angeles, he lived under military occupation in the West Bank, unable to leave when he was sick and in need of medical care. In more recent years Israel has tried to segregate buses there so that Israelis would not have to ride with Palestinians. The Prime Minister went so far as to exclaim that there would be no Palestinian state as long as he was in power. All the while, more settlements go up. More rockets are fired. More strikes are launched on Gaza. More innocent civilians die.

I was in tenth grade and about to travel abroad alone for the first time. I had just received my new passport in the mail and my mother and I opened it together at the dining room table. It was a hot day in May in Los Angeles, California.

I haven't been back to Jerusalem since we left in 1998. I have forgotten all the Hebrew I once spoke. My parents relinquished my Israeli citizenship when we moved back to the States, too, so that I wouldn't have to serve in the army when I came of age. A few glitchy memories linger in my mind from my youngest years: A rabbit biting my finger at gan (nursery school), me hiding behind my mother as she spoke in English with the teacher, me climbing out of my crib in our apartment. Mostly though, Jerusalem is a blank in my mind. I have an incredibly clear memory of climbing over boxes at our apartment in New York City, presumably right after we moved back, in 1998.

My mother points at my passport, "There's no country here. Do you know why?"

"No."

"It's because Jerusalem is disputed territory. Israel and Palestine both claim it as their capital."

When we lived there my father would travel to Saudi Arabia and Lebanon and Iraq and Algeria and other Arab countries. He used a second passport so that those governments didn't know he had ever been to Israel, because they would not let people in who had been. He has interviewed Bibi Netanyahu, members of Hamas, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia. He and my mother have seen the terror of both sides of the battle. In an Op-Ed my father wrote for the LATimes in 2011 he called Jerusalem "the disputed city we once lived in, a city of Palestinians and Israelis, of Christians, Jews and Muslims, of checkpoints and bombings, of ancient beauty and religious passion."

Yesterday's Supreme Court decision that naturalized Americans born in Jerusalem are not allowed to name Israel as their country of birth on passports makes me remember all this. I was born to two American journalist parents in Jerusalem precisely because it is disputed territory. If Jerusalem were simply a part of Israel, there would have been no reason for my parents to be there reporting. Though it may not have been when I was in tenth grade, my passport is now a fierce reminder of the infant in my mother's novel, a child who is forbidden internationally to have a name for his country, or even to claim Jerusalem as his home. I am infinitely willing to sacrifice one line on a passport in recognition of children like him and in recognition of the rich, complex, painful, and constant history of Jerusalem.