Everyone from the President on down seems concerned about how the midterm electorate's composition hurts Democrats. Some predict fewer younger voters turning out. Others point the finger at minorities. Still others say women voters' lagging turnout will hurt Democrats. Then of course there is the perennial Democratic turnout pot-o-gold: unmarried women.

But it's just not accurate to place blame for Democrats' struggles at the feet of women, young people and minorities. Simply looking up past numbers, rather than parroting conventional wisdom, brings this into stark relief.

First, turnout across the board is lower in midterm elections. The census shows a 16-point gap between presidential turnout and midterm turnout between 2006 and 2012 (and a 15-point gap among whites). So the composition of the electorate stays similar, even as fewer voters overall turn out. The press frequently gets this wrong when talking about gender. Politico calls it "simple logic" that Democrats do better when women vote. And a recent Washington Post article headline jokes "Obama really, really needs women to vote." Yet women have been a majority of the electorate in every single election since 1980. If women's turnout always meant a Democratic victory, there would be no more competitive races.

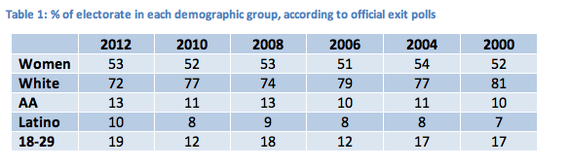

The table below shows the percentage of each year's electorate that has been female, white, African-American, Latino, or 18-29, according to official exit polls. As you can see, age does bounce around between midterm years and presidential years. But gender varies essentially not at all, and African-American and Latino turnout, as a percentage of the total electorate, only varies slightly.

Second, Democratic performance--not turnout--differentiated the last two midterms.

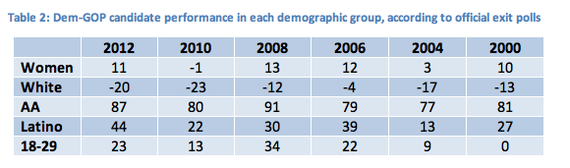

Table 2 below shows the Democratic advantage in each of same six elections for each of the same demographic groups. In 2010 Democratic performance was low across all subgroups. In 2006, the previous midterm, Democratic performance was higher across all subgroups. (And consistent among African-Americans.)

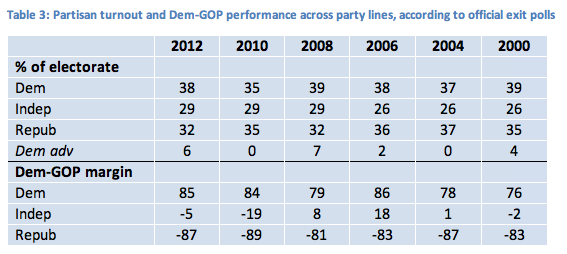

Some may say, "Well, Democratic-leaning women, minorities, and younger people could have stayed home in 2010!" But the partisan composition of the electorate is not the answer either. The table below shows Democrats and Republicans were equal or near-equal portions of the midterm electorates. But between the two midterms, there was a drop in Democratic performance across all three partisan groups, particularly among independents.

Third, turnout among unmarried women was the same in both 2006 and 2010. Since not all exit polls show the vote by unmarried women, we turn to the census and self-reported vote behavior. For both midterms, a nearly identical percentage of unmarried women citizens voted (2010: 36%, 2006: 37%). There is also no difference in turnout among unmarried women under 24 years old (2010: 22%, 2006: 23%).

My very first post--over six years ago--at the original pollster.com explored how political coverage portrayed women as falling down on the job when it comes to voting. Sadly, not much has changed since then.

Of course higher Democratic turnout boosts Democratic chances. We only need to look at Republicans' systematic vote suppression efforts to know they agree. And make no mistake, my record on urging Democrats to make their messaging more women-centric is long.

But there is more to our past success--and failures--than simply getting more women, minorities and young people to the polls. Turnout doesn't exist in a vacuum, and demographics aren't destiny. As in the past two midterms, the party with the overall message advantage--not merely a turnout advantage--won decisively. Right now Democrats are far less unpopular than Republicans, hold the advantage in party identification, and hold a slight advantage in the generic ballot. If Democrats are to stave off tough challenges in November, it'll need to be because of messaging, not just a secret turnout sauce.