Problem-solving skills are a powerful combination of intuition and learned behavior.

- Some people (including Justin Bieber) can solve a Rubik's cube puzzle in less than two minutes; others remain hopelessly stumped.

- Some folks take delight in the challenge of solving a crossword puzzle; others lack the necessary combination of vocabulary and cultural literacy that would allow them to make a dent in the puzzle's grid.

- Some musicians can sight read music from the printed page, but not everyone can play something they have heard by ear (or effortlessly transpose a piece of music from one key to another).

- Taken by themselves, these skills may not seem to overlap. However, they demonstrate the way a nimble mind quickly reacts to challenges and can deftly overcome unexpected obstacles.

Nowhere are such skills showcased as brilliantly as in the physical comedy scenes featuring some of the great artists from the silent film era. Back in those days there was no such thing as computer-generated imagery (CGI). The intricate plotting and execution of each stunt, sight gag, or elaborate chase scene relied on fertile imaginations creating a meticulously-planned, fast-moving series of comedic events that could be executed by an athletic actor of remarkable agility. Consider the following two sequences: Buster Keaton's epic chase sequence from 1925's Seven Chances and Harold Lloyd's prolonged climb to the top of a Los Angeles office building in 1923's Safety Last!

The 2015 San Francisco Silent Film Festival included works by two of the silent era's comic geniuses. One was a titan of silent film who personally took great care to make sure that his work was preserved for future generations. The other was a relatively unknown actor/animator whose prodigious imagination (and fascination with mechanical devices) combined physical comedy with dazzling feats of surrealism.

* * * * * * * * * *

Five years after Safety Last!, Harold Lloyd made his final silent film (the only one to receive an Academy Award nomination). Directed by Ted Wilde (who was nominated in the short-lived category of Best Comedy Director), Speedy told the tale of a baseball fan who was unable to hold onto a job. Whether working as a soda jerk or driving a taxi, Harold "Speedy" Swift's mind could easily be distracted by thinking about baseball or his girlfriend, Jane (Ann Christy).

Shot in Hollywood and on location in New York, Speedy was the last of Harold Lloyd's silents to be released in theatres. The film's plot revolves around Speedy's attempt to save the last horse-drawn streetcar in New York from being put out of business by a group of corporate thugs who want to monopolize Manhattan's transit system. Why should any of this matter to Speedy? The horsecar is owned by Jane's grandfather, "Pop" Dillon (Bert Woodruff).

There are many wonderful moments in Speedy, starting with the scene in which Lloyd is seen working as a soda jerk and including the segment in which Babe Ruth plays a terrified passenger while Speedy attempts to drive him to Yankee Stadium. The trick, of course, is that the starstruck Speedy can't stop looking back at his idol and chattering on and on as his taxi negotiates a hair-raising course through traffic.

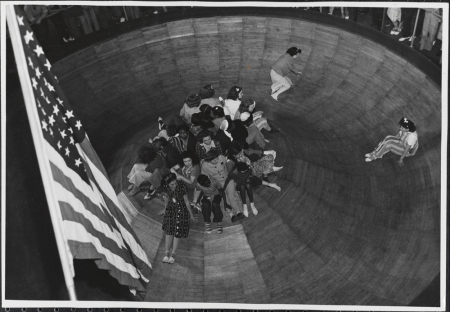

One of my favorite segments takes place when Speedy takes Jane on a trip to Coney Island's amusement parks. Although Luna Park (which was built in 1903) was destroyed by fire in 1944, I have fond memories of my family's visits to George C. Tilyou's Steeplechase Park (built in 1897) during the 1950s. It gave me great joy to see the rides I used to love (the mechanical horse race, the whirlpool, the rotating barrels, the giant slides and the funhouse mirrors which distort a person's size and shape).

Like many of his films, Speedy (which was accompanied by the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra) is filled with lightning quick sight gags which are often breathtaking in their conception. The following clip, in which Speedy and Jane travel to Coney Island on the subway, is chock full of them.

By the time Speedy finds himself smack dab in the biggest crisis of the day, the film's grand chase through New York is a masterpiece of ingenuity and comic timing.

* * * * * * * * * *

On March 22, 1962, when Harold Rome's new musical entitled I Can Get It For You Wholesale opened on Broadway at the Shubert Theatre, audiences were amused by one of the biographies appearing in their Playbill. As the actress making her Broadway debut in the role of Miss Marmelstein, the copy for Barbra Streisand's blurb began "Born in Madagascar and reared in Rangoon, she attended Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn..."

During the 2014 San Francisco Silent Film Festival, Serge Bromberg introduced the audience to the work of Max Linder with a screening of 1921's Seven Years Bad Luck. This year he introduced and accompanied four hilarious shorts -- A Wild Roomer (1926), Now You Tell One (1926), Many A Slip (1927), and There It Is (1928) in a program entitled The Amazing Charley Bowers.

As with Max Linder, few in the audience had ever heard of Bowers (who died in 1946 at the age of 57). In his program note, Sean Axmaker wrote:

More than 40 years after his rediscovery, Bowers remains an enigma with a biography wrapped in myth and tall tales. What is known of his early years is largely conjecture, informed by fanciful studio press releases and Bowers's even less reliable accounts.

According to these anecdotes, he's the son of a countess, learned to walk a tightrope at the age of five, was kidnapped by circus gypsies at six, and worked variously as a bronco buster, jockey, cowboy, horse trainer, and circus acrobat before an injury grounded him.

What can be confirmed (thanks in large part to research by film scholar and historian Rob King) is that he worked as a newspaper cartoonist, which led to a career as an animator on early cartoon series such as The Katzenjammer Kids and Bringing Up Father.

In 1916 he was put in charge of the Mutt and Jeff series and wrote, produced, and directed more than two hundred cartoons between 1916 and 1926. Sometime in the 1920s he began experimenting with puppet animation and stop motion techniques.

Bowers transformed himself into a silent comic without the training that shaped the great performers. It's no surprise that he lacks the physical polish and comic timing of his contemporaries, but he's perfectly appealing as a plucky, energetic hero willing to try anything in the name of scientific inquiry.

Like Buster Keaton's films, Bowers's films share a fascination with machines and technology. But where Keaton took an engineer's delight in the operations and mechanical possibilities of steam engines and paddle boats, Bowers applied the limitless imagination of a cartoonist and the tools of stop motion animation to push the conceptual possibilities of his devices beyond the limitations of physics and into the realm of fantasy.

As the audience in the Castro Theatre kept dissolving into hysterical laughter, it became obvious that (a) Bowers was a comic genius, and (b) seeing is believing.

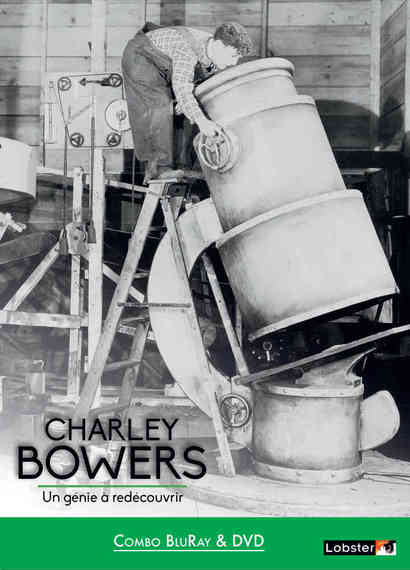

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Serge Bromberg, 15 surviving Charley Bowers films are available in a two-disc, four-hour DVD set that has been released by Image Entertainment (USA) and Bromberg's company, Lobster Films of France. It's also available on Netflix.

Poster art for Charley Bowers: A Genius Rediscovered

In the meantime, here are two of the shorts that were shown at the festival. Enjoy!

To read more of George Heymont go to My Cultural Landscape