Photograph by Mariam Magsi

Sunday morning in Harlem, 2016, and on the radio plays Whenever I Call You 'Friend' the duet sung by Kenny Loggins and Stevie Nicks. Too slick, too sweet I heard critics scoff but I think about how profound it must have been in 1978 to hear a man hold up friendship as a crucial component to love.

Before the 1970s, did men sing odes to friendship between the sexes? My radio awakening begins after 1974. So much is still awful for women but I hear prophets in the car, in my bedroom at night. Queen's Freddie Mercury declares his lover his "best friend" in the song bass guitarist John Deacon wrote for his wife. Freddie may have been gay but that didn't undercut the message to little girl me, who absorbed his loving kindness as much as I did Rod Stewart's request to loosen off that pretty French gown. Those lines from Stevie Wonder's That Girl: "She doesn't use her love to make him weak, she uses love to keep him strong"? I imagined that's what the best women did for their men. Didn't matter that in 2015, a fan would yell out "That Girl" during a concert at Madison Square Garden and Steveland Morris would joke about hitting "that girl" because she broke his heart.

Yes it does matter. My hero riffed on intimate violence. Until I type this, I conspire to submerge the memory for good.

Upstairs, my husband sleeps. Or he watches MSNBC Sunday shows with his Ipad on his chest. I am writing. He never looks over my shoulder. Whenever I Call You 'Friend' plays and I think: my husband is my friend. This is what I incinerated relationships to get to, this hard-earned equilibrium. I sing along but I'm bested by the harmonies and held notes. Still I try.

A few weeks later I'll pick up the New York Times to see the Bronx apartment door where a down-spiraling man thought he could stab his wife to death--and did. I'll scream in my head stop killing us. No one belongs to anyone. But how many of us refuse to believe this? I live in my bubble of protection, one that can be singed away so easily by an aggressor. Sovereignty is fraught in family. The notion that I am not chattel, and that the courts will agree--this is new. The promise that my beloved will cherish my friendship? This is me living and not dead.

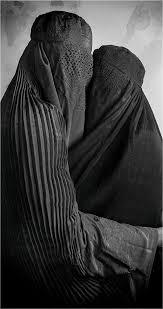

That Sunday afternoon I attend Of Note magazine's "Art of the Burqa" co-hosted by the Afghan Women's Writing Project. Afghanistan has been called the most dangerous place for women, a country where war and harsh patriarchal norms keep women subject to violence. Head-to-toe burqa use is widespread. We will hear the poetry of those who wish to throw off their blue cages. We will absorb the fine art of those who are free enough to play with the cloth. Like Mariam Magsi's photograph, when she covered two same-sex lovers in burqas and shot their embrace. Or Hangama Amiri's painting, where she placed her burqa-clad mother inside of an art museum, surrounded by, yet separate from, the landscapes on the walls.

Poet Hajar is a university student only a few months into her new American life. When she stands up to read Roya's "Remembering Fifteen" I can already hear the mother's refrain in the poem: be like other people, be like other people. But the speaker in this poem wants to discover love for herself: she does not want to be treated as a goat to be sold into marriage. Yet, how to speak up when the decisions of parents must be obeyed? The poem states no solution. Instead, offers itself.

The final question for the panel: What do you hope for the future? Hajar had just written a poem about a woman struggling after her progressive fiancé hits her with his belt. This is a poem she has made into a song here in America. She takes the microphone: What I hope for is friendship. More friendship between men and women, husbands and wives, fathers and daughters. And I am in the audience clapping to her answer and I can feel that packed room think, feel, and perhaps take stock of how this kind of relationship helps us transcend what is hateful about human life: our refusal to see the forever in every single one of us, not just the ones we choose.