We've recently been witness to the fact that politics can definitely be cinematic. Maybe not always in a good way, but it is. So is cinema political in return?

When we watch a film, we make a choice that is oftentimes political, because it involves gender, ethnicity, religion and our own personal beliefs. With our money, we help shape the choices Hollywood, Bollywood and world cinema filmmakers will make in the future. Say you watch the latest Fast & Furious film, or instead choose a cozy viewing of Jeff Nichols' Loving. The first will help perpetuate a certain kind of hyper popular, testosterone filled moviemaking, while the latter will more likely inspire cultural understanding, across gender and race.

I believe every movie ticket we buy is a vote, and it may end up counting more in the long run than any vote in the US election.

So if we're talking Arab cinema, well that term is undeniably charged, at its very roots. These days, the country of origin of a film and the theme of a particular movie are all inescapably political if we are talking modern Arab cinema.

At the recent Dubai International Film Festival, which neatly closes the year for filmmakers, film buffs and distributors from the MENA region, quite a few films that were in the line-up, as well as a couple conspicuously missing, all showed political choices. Personally, I felt discouraged coming into the festival, with so much chaos enveloping the Region and spilling beyond the Middle East, but in typical Dubai fashion, DIFF managed to ease my mind, somehow.

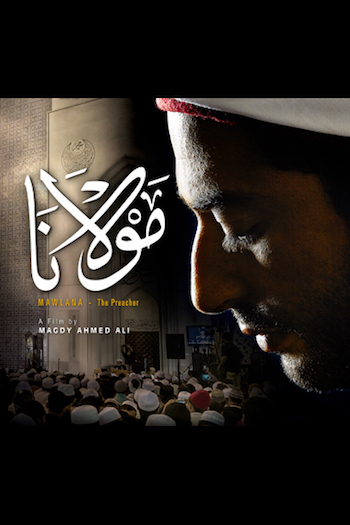

Nearly six years after the revolutions of the Arab Spring, Egyptian filmmakers are finally steering clear of the topic and returning to what they do best, tell beautiful stories. Two films struck a chord with me at this year's DIFF, Yousry Nasrallah's Brooks, Meadows and Lovely Faces, and Magdy Ahmed Aly's Mawlana ("The Preacher"). Nasrallah's films have always dealt with the humanity beneath the politics, and Brooks is no exception. It is an ode to "Love, food, freedom and dignity," as Nasrallah himself introduced it at the Dubai screening and I'll add, a damn great film about the sensuality of women in the Arab world. In a post-viewing interview I asked the Maestro if he feels that his film is political in any way, and he replied, "there is a political gesture in a period of austerity when death is glorified, in making a film which glorifies abundance, sexuality, sensuality, freedom -- it is transgressive by default." He concluded, "the world is becoming more and more conservative, all over, and making a film so irreverent to whatever is conservative is political; it's something to remind you that we're not like that, it is a film in the present tense."

Mawlana on the other hand is a movie that jumps out of today's all-too-common headlines. Actually, the film screened at DIFF within twenty-four hours of the latest Coptic Christian church bombing in Cairo and there is a scene in the movie so eerily like real life that it could not be ignored or dismissed as just cinema. In fact, Mawlana is based on the novel The Televangelist by journalist Ibrahim Eissa who through his book aimed to show how religion can be misused for the sake of politics. Prevented from writing the story in 2009, Mawlana became a tale that could only be told through the revolution, but which thankfully does not delve into the usual turns of the uprising. And at the center of the film, stands a man, a religious man whose humanity makes the story thoroughly spellbinding.

Mawlana on the other hand is a movie that jumps out of today's all-too-common headlines. Actually, the film screened at DIFF within twenty-four hours of the latest Coptic Christian church bombing in Cairo and there is a scene in the movie so eerily like real life that it could not be ignored or dismissed as just cinema. In fact, Mawlana is based on the novel The Televangelist by journalist Ibrahim Eissa who through his book aimed to show how religion can be misused for the sake of politics. Prevented from writing the story in 2009, Mawlana became a tale that could only be told through the revolution, but which thankfully does not delve into the usual turns of the uprising. And at the center of the film, stands a man, a religious man whose humanity makes the story thoroughly spellbinding.

From Syria these days there are a lot of documentaries told through the shaky handheld cameras of anti-regime rebels. The work of artists who have been persecuted by the Al Assad government and with their smartphones, small camcorders, by any means necessary, are portraying their side of the story. Usually helmed by a Western man, they are most often the stories of women such as Obaidah Zytoon as edited and viewed by Danish filmmaker Andreas Dalsgaard in The War Show, an interesting effort. From my own very personal prospective, a bit problematic because it only shows the politically correct side of the story, the one the media is already telling the world in their own narrative and in order to truly understand something I believe all sides must be at least discussed.

While Egypt may turn out to be OK after all, in Tunisia, the country which sparked the Arab Spring, there are politics at play even before you and I can get to watch a film.

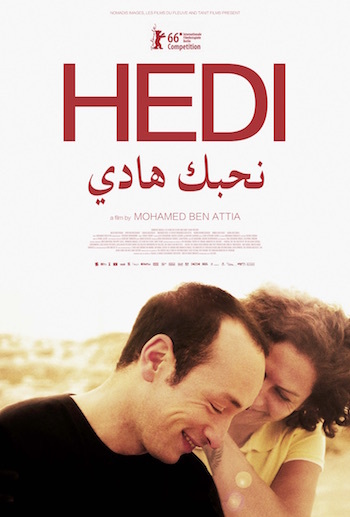

Hedi filmmaker Mohamed Ben Attia gently scoffed at me in Berlin when I pointed out that his film is quite courageous in its choice of images. A man and a woman having sex, in all its details, to me represents courage in Arab cinema regardless of its origin. He explained, "I was even reproached that the film is somehow too chaste; it was my choice to show a love story in a very natural way, maybe naive but that's what happens when you fall in love. What is tough for Tunisian audiences is not so much to accept nudity or the sex scene, but the fact of having violence around all of that, adultery, incest or rape. But nudity and sex, they are used to watching American and French movies."

Hedi filmmaker Mohamed Ben Attia gently scoffed at me in Berlin when I pointed out that his film is quite courageous in its choice of images. A man and a woman having sex, in all its details, to me represents courage in Arab cinema regardless of its origin. He explained, "I was even reproached that the film is somehow too chaste; it was my choice to show a love story in a very natural way, maybe naive but that's what happens when you fall in love. What is tough for Tunisian audiences is not so much to accept nudity or the sex scene, but the fact of having violence around all of that, adultery, incest or rape. But nudity and sex, they are used to watching American and French movies."

So more risqué images, and hidden-in-plain-view themes that both praise and criticize Tunisia as a country and its people, should mean a freer cinema culture, right? Unfortunately not, as the recent Oscar nominations from the country pointed out. One committee -- the official one -- nominated Ridha Behi's latest The Flower of Aleppo, while another committee popped up out of left field and nominated As I Open My Eyes by Leyla Bouzid, which premiered at the 2015 Venice Film Festival. That resulted in the disqualification of both films, and so Tunisia didn't even enter in the running for a Foreign Language Oscar in 2017.

Palestine this year isn't well represented either, slim pickings I'd say, and the decision to submit Hany Abu-Assad's The Idol to the Foreign Language Oscar race was more out of dire need than the value of the film itself. To yours truly, it's not a surprise the film didn't make the shortlist. The reigning triumvirate of great contemporary Palestinian cinema is made up of Abu-Assad, Annemarie Jacir and Najwa Najjar. So, while we eagerly anticipate projects from both Jacir and Najjar, which are currently in development, there isn't much else to say about Palestinian cinema. At this year's DIFF, two shorts and a medium sized feature about militant cinema in the Middle East, titled Off Frame AKA Revolution Until Victory were the only Palestinian film presence.

Lebanon will always mean for me the films of Nadine Labaki. I know, I can hear the collective moans, I'm selling the country short if I refuse to take into account other filmmakers. But I attribute to Labaki's sultry Caramel my passion for Arab cinema and until she makes her next film, I'll simply have to turn elsewhere, country-wise, to get my cinematic entertainment.

In fact, the previous two points highlight the fact that women filmmakers have always been a strongpoint of the Arab film industry, with numbers much higher than their Western counterparts. I asked Shivani Pandya, the Managing Director of DIFF about this incredible aspect of diversity, in a part of the world where the Western media would like us to believe women are kept down and at home. She admitted, "I'm super proud that in this part of the world we have such a high representation of women directors. People keep saying, what are you doing to promote this? And we really don't have to do much. They [women filmmakers] want to compete on even keel, on an even platform, and that's what we are providing them and have great numbers coming through. So at any given time we have more than 30 percent women directors. For me, it's a great average!"

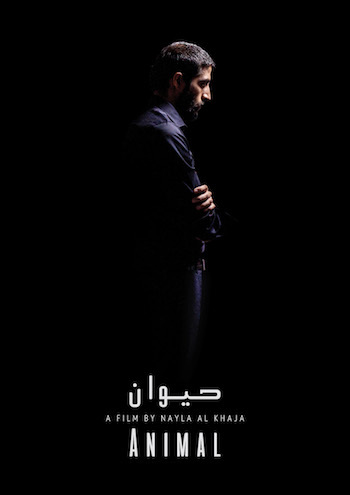

In the UAE alone, the numbers seem to be even higher. Year after year, women filmmakers like Nayla Al Khaja, Noujoum Al Ghanem and Amal Al Agroobi are showing the boys just how it's done and their work is deeper, more soulful and better grounded than that of their male counterparts. Take for example Al Khaja's latest Animal, a fifteen minute short she plans to develop into a full feature. Autobiographical and deeply personal, Animal tells the story of a family held in the psychological stronghold of a bully father -- and is based on Al Khaja's own experience growing up. I asked Al Khaja about being a kind of ambassador for her culture. She answered readily, "my husband said that to me, about being an actual ambassador for my country!" And continued, "because, he said, you present your country in a good way, it's not too polished but it's not too dark, it's realistic" and anyway, Al Khaja added, "most filmmakers who are true to the nature of their artwork are ambassadors of sorts."

In the UAE alone, the numbers seem to be even higher. Year after year, women filmmakers like Nayla Al Khaja, Noujoum Al Ghanem and Amal Al Agroobi are showing the boys just how it's done and their work is deeper, more soulful and better grounded than that of their male counterparts. Take for example Al Khaja's latest Animal, a fifteen minute short she plans to develop into a full feature. Autobiographical and deeply personal, Animal tells the story of a family held in the psychological stronghold of a bully father -- and is based on Al Khaja's own experience growing up. I asked Al Khaja about being a kind of ambassador for her culture. She answered readily, "my husband said that to me, about being an actual ambassador for my country!" And continued, "because, he said, you present your country in a good way, it's not too polished but it's not too dark, it's realistic" and anyway, Al Khaja added, "most filmmakers who are true to the nature of their artwork are ambassadors of sorts."

Taking its cue from the Khaleeji tradition of storytelling, which is as ingrained in the culture of the UAE as family values, Arabic coffee and glistening sand dunes, the Dubai Film and TV Commission understood the importance of having a YouTube hub in the Region. After all, even a blockbuster venture like Bassem Youssef's original Al-Bernameg ("The Show") got its start as an internet show. I asked the Commissioner Jamal Al Sharif about this addition to the already healthy cinema industry the Commission is helping to build in Dubai.

"The closest YouTube hub is in London and India and the Middle East didn't have one. That's why I worked with them for the past year and a half on positioning and creating a platform for them in Dubai Studio City, they will be there by the second quarter of 2017. We have already reserved the location for them, it's going right now through the whole facelift of becoming a YouTube space. It's going to be a destination where creators can go and create their content comfortably and YouTube will provide them with all the necessities: Studio, post-production, lighting cameras, and then a platform to distribute through their YouTube channel. You go in there and you are a creator, and you have an account with more than 10,000 in viewership and you have content. And they help you to create that content produce that content, do the post-production, use their equipment all at no cost. And of course, it's an enabler. It's a lounge when you'll also meet other creators, who will help you."

Al Sharif also brought up the need for cross pollination, and independent cinema of all cultures traveling across borders. "I miss watching foreign films, which I only watch on Emirates Airlines. The last couple of times when I traveled I saw Spanish and Italian movies, subtitled of course, and it's beautiful! That's the problem with the Arab world. I don't see any single Arab content on any TV in the West, or even on their airlines. Sadly, they are only carried on our airlines -- Etihad, Emirates and Qatar Airways. What about in the cinemas in the West? That's the part that is missing. Even Japanese, Italian or Spanish films, you don't see them in the theaters here. Why?" Arab cinema this year is once again conspicuously missing from the Oscar shortlist, and even more so in theaters.

Even in the Middle East, a film from Egypt, such as the recent Clash is only shown in Arabic without subtitles, thus excluding the entire expat contingency which makes up the majority of the population in a country like the UAE. Mohamed Diab's Clash opened this year's Cannes Un Certain Regard section where it definitely was subtitled for world cinema audiences.

To fill the gap of arthouse cinema, a concept still in need to catch on as far as numbers go in the Middle East, the task is left to organizations like Zawya in Cairo, which coordinates with existing movie houses across Egypt to create a series of art-house cinema screens across the country. In Beirut there is Metropolis, a labor of love where films like Planetarium starring Natalie Portman can alternate between the latest Xavier Dolan project and Café Society by Woody Allen. Last but not least, in the UAE there are two entities Cinema Akil and The Scene Club, both featuring programs that alternate venues, for the time being, and both founded by phenomenal women -- Butheina Kazim and filmmaker Al Khaja respectively. Later in 2017, in fact Cinema Akil will move into its permanent location on Arserkal Avenue in the cool district of Al Quoz in Dubai, where cinema magic will be made on a regular basis. Inshallah.

Saudi Arabia has joined in with a slew of young, vibrant, enthusiastic filmmakers with a vision. My favorites include Haifaa Al Mansour, whose Wadjda created ripples around the world, and Mahmoud Sabbagh. Premiered in Berlin and showcased throughout the world, Sabbagh's Barakah Meets Barakah is the kind of film that creates a movement and that movement may just turn out to be the birth of actual cinema houses in the restrictive Kingdom of Saudi Arabia -- something only dreamed about till now. Incidentally, both films were submitted by Saudi to the Foreign Language Oscar race --for 2014 and 2017 respectively -- though neither made the final cut. But the pride of a whole country to me speak louder than receiving a tiny golden statuette.

All in all, Arab cinema seems to be going steady and perhaps the best description of the parallel between this particular cinema of the world and its protective yearly home in Dubai, DIFF, was explained by the festival's Chairman Abdulhamid Juma, to whom I'll leave the last words of this piece. "I think we have changed gear. You know when you are driving on the highway and you are really cruising right? And everybody in that car is having a really useful and beautiful time. And music is playing." He continued, "our music are the films, the passengers are the filmmakers, and there are a lot of people waving on the street and they are the audience watching the films. And it's a beautiful sunny day, we have a destination, we know where we're going but we are enjoying the ride." He concluded wisely that for the year ahead his wish is to keep "the momentum, hopefully. I want you to tell me [next year] that there was a real change and it wasn't just a lucky edition. We have left the city, and are now on the highway, and nothing can stop us because there is no traffic anymore."

Top photo of Eva Longoria on the DIFF red carpet by Neilson Barnard/Getty Images for DIFF; all images used with permission.