The Royal Academy's Rubens and His Legacy raises more questions than answers and make me wonder why the English find it so difficult to understand or even tolerate him. The clearest example of this confusion comes from the exhibition's fiercest critic, The Guardian's Jonathan Jones.

Jones is right at pointing out that the curators' decision to turn the whole exhibition into a Rubensian assortment of works by artists allegedly influenced by him, is a bad idea. The examples that he chose, however, to illustrate his point are so wrong that they evidence a worrying lack of awareness. From the beginning, Jones broadcasts his frustration with the curators' decision to place a painting by John Constable at the beginning of the show, nearby one of Rubens' landscapes.

In his own words: 'It is hard to think of a painter who has less in common with Rubens. But the curators have spotted one connection I never guessed: they both painted rainbows. That is the RA's less than precise approach to art history. So Rubens invented the rainbow, apparently. Rubens and His Legacy tries to distort the rich and complex story of art to fit a simplistic big idea. Constable, Turner and Gainsborough - all of whose landscapes are juxtaposed with those of Rubens here - were fascinated by the great European masters: their biggest "influence" was the 17th-century French landscape artist Claude. So why try to claim that Rubens was somehow their one true source?'

Even though it is true that Constable, Turner and Gainsborough's landscapes were influenced by Claude, they were more so by Rubens. While Claude's landscapes are idealised arcadian perfections with mythological figures, in Rubens' Het Steen we see a conflation of this and the Late-Renaissance Flemish tradition of Patimir, Brueghel and Bosch. It is that human inflicted ruggedness that Constable observes in Rubens and that is enough of a reason to suggest a curatorial link.

When referring to the curators' decision to include a Warhol portrait of Jackie Kennedy besides one by Rubens, Jones says: 'Please, tell me, that I am dreaming it! I really don't see any possible similarity between Rubens and Warhol'. Well, what about the fact that both were artistic superstars that used the pictorial surface as a space where theirs and their sitters' identities were negotiated. It is a fact that when we look at one of Warhol's Marilyns, we see her facial features but we can also see him through his style'. Another similarity between these two artists has to do with the fact that they both used to leave the execution of their paintings to their employees.

This confusion takes us to the real problem of a show that does not appear to do itself many favours by placing pieces by Rebecca Warren and Sarah Lucas along masterpieces by Rubens' and Andy Warhol. I think that the problem with this show is that it does not do what it promises to do. Even though the show's title includes the word 'legacy', there is no distinction made between 'allusion' and 'influence' for the former has to do with borrowing while the latter is often unconscious.

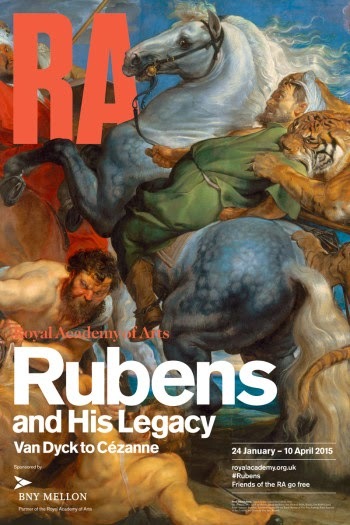

Jonathan Jones, however, becomes insulting when saying that Rubens was not only just a courtier but also 'a supreme decorator who never touches profundity. Thus, he will never be a Rembrandt, Caravaggio or Velazquez. These three geniuses all lived in the same age that Rubens dominated. But where he created seductive confections, they tell a more serious truth'. Here, Jones misunderstands the use of 'chiaroscuro' with 'the ability to convey serious truth through painting'. Rubens' art should, however, be understood as an alchemic manipulation of something dead (pigments) into something alive (Inmortal Art). His works has that centrifugal drive that demands an over-crowded pictorial space compositionally organised as a wheel which transforms the painting itself into an allegory of the cycle of life. Besides, while Velazquez used to be a painter of peace (for even his war paintings depict people at rest), Rubens is a painter of violence. There is always conflict and blood in his paintings to the point that it is not too far fetched to think that he uses blood as an allegory of painting for, at the end of the day, when one has nothing else to paint with, there is always blood.