New York sidewalks and chalk have been partners with the city's women for generations. Setting the scene for childhood games of hopscotch and jump rope, chalking on the city's pavements is a ritual of growing up female in the city. New York sidewalks also bear the weight of the city's footsteps and the hopes and dreams of New York women. So too, they bear the weight of dreams unrealized or cut short, however light or fleeting the step of the dreamer. In this way, New York's sidewalks link generations of women in the city, their hope and their despair.

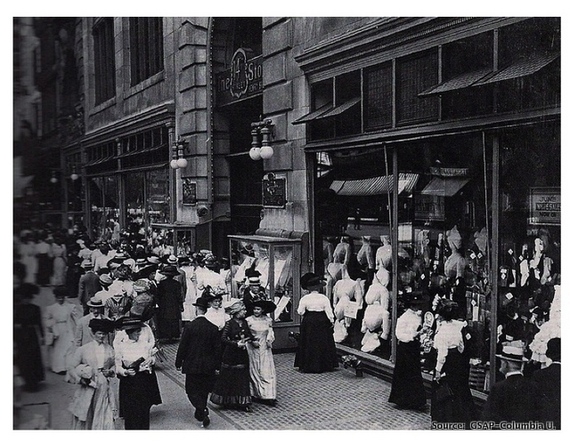

At the turn of the 20th century, New York's fashionable women strolled along the sidewalk of the city's shopping district, Ladies' Mile. Here, women admired displays of the latest styles of shirtwaists, a type of blouse that epitomized the modern American woman, in department store windows. Poised and fashionable, a woman wearing a shirtwaist was the ideal modern woman. But her stylish figure came at a price that was paid by other women working long hours for low wages in the city's miserable sweatshops.

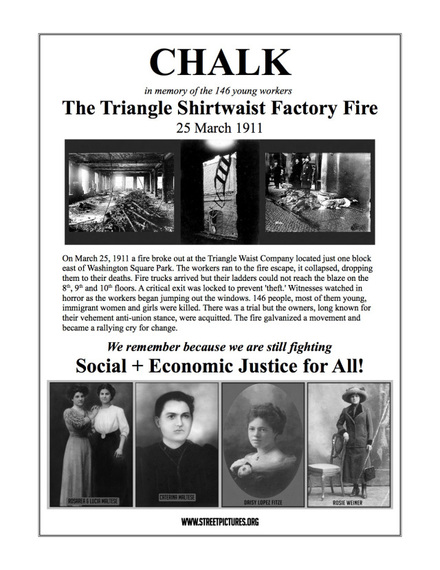

At the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in Lower Manhattan, women sewed shirtwaists six days a week. Around 500 women were crowded into three floors behind long rows of sewing machines. On March 25, 1911, shortly before closing on a Saturday afternoon, fire broke out.

Photo Credit: Photographer unknown, c. 1900, Kheel Center, Cornell University, trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu

Workers at the factory found their path to escape blocked by locked doors with only a single fire escape. Management fled the factory without warning those who toiled in crowded and unsafe conditions. Firefighters arrived with ladders that were too short to reach the eighth, ninth and tenth floors where the fire raged. As firefighters and police watched helplessly, women found their only choice was to perish in the flames or jump from the windows and plummet to their deaths on the pavement.

That day, 146 workers, mostly young immigrant women and girls, died in the fire. The youngest of the victims was fourteen years old; the oldest was forty-three years old. On April 5, 1911, over 100,000 New Yorkers took to the streets in pouring rain for a symbolic funeral procession. On the sidewalks of the city, nearly half a million more watched and grieved.

Photo Credit: Photographer unknown, 1911, Courtesy of Kheel Center, Cornell University, trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu

Those sidewalks, where once thousands mourned, are now the focus of Ruth Sergel, a New York City artist. Using the city pavement as her canvas, Sergel has devised a way to honor the lives and dreams of these women who perished in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. Sergel organizes Chalk, an art project that she labels a "public intervention" in which the struggle for social and economic justice continues for today's garment workers.

In Chalk, volunteers use colored sidewalk chalk to inscribe the name and age of each woman on the pavement in front of her home. A small sign is taped to her building, asking New Yorkers to remember her life, the tragedy of the fire and the continued fight for economic justice for all women. It's a ritual repeated each March 25th, the anniversary of the tragedy. Through Chalk, one day each year, these women become again, however briefly, part of the humanity that treads the sidewalks of the city.

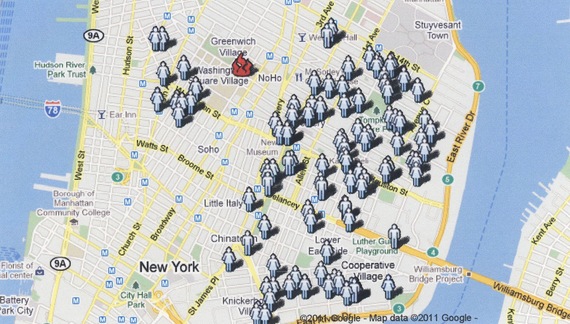

To participate in Chalk, volunteers go to Ruth's website. Here, a map is populated with figures marking the spot where each of the victims of the fire lived. On the website-map, the figures of women mostly cluster on the streets of the Lower East Side appearing like piled up like pieces of fabric cut out from chalked patterns. Through Chalk, these figures are stitched, piece by piece, not into shirtwaists, but into stories of New York women.

Photo Credit: Lewis Hine, 1910, Courtesy of Kheel Center, Cornell University, trianglefire.ilr.cornell.edu

The names on the list speak of women from southern Italy and Jews from the shtetls of Eastern Europe. Each pattern piece tells the story of a voyage in steerage from Europe, a life in the tenements of New York City, and a beautiful American dream, cut short by the flames of the fire.

The map is actually a new chapter in the story of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. At the time of the tragedy in 1911, a complete list of victims did not exist. Historian David von Drehle compiled the most authoritative list of 140 victims for his 2003 book on the Triangle: The Fire That Changed America. The six missing victims were finally identified by amateur historian and genealogist Michael Hirsch, almost 100 years after the tragedy. He was determined to change anonymous victims into known women with stories to tell.

Picture credit: Courtesy of streetpictures.org/chalk

A resident of the Lower East Side, Hirsch identified the women using public documents, family interviews, and reading ethnic newspapers including the Yiddish-language Jewish Daily Forward and Il Giornale Italiano. He visited the sixteen cemeteries holding the remains of the victims.

From the tiny figures on the map, I selected Maria Tortorelli Lauletti (age 33) and Isabella Tortorelli (age 17). Both women lived on Thompson Street, a stone's throw from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory on Washington Street. Maria and Isabella were one of several pairs of sisters working at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory that day.

The first year, I invited a friend to join me in Chalk to honor these two sisters. We imagined the walk Maria and Isabella took to work each morning from Thompson Street to Washington Street. We imagined them eating lunch in Washington Square in late March, a time when New York weather can carry the promise of good times to come. We imagined them stopping at St. Anthony of Padua church on Sullivan Street to light a candle or say a prayer. We imagined that some of their prayers involved giving thanks for finding work together in a building so modern that it even had an elevator that led to the top floors where they worked. But most of all, we thought of the tragedy of these two lives, cut short. By the end of that afternoon, our hands were covered with the dust of colored chalk. We transferred traces of that chalk onto our faces as we wiped away our tears.

Photo Credit: maryannerussell.com

Over the next years, as the details of the Tortorelli sisters' lives were revealed, I latched on to the hopes and dreams of the sisters for their new lives in America. Maria, I learned, was a widow with five children. I looked at the façade of the building at 133 Thompson Street and began to think of these sisters as women, not just as victims. I wondered: Which windows were hers? What hopes were in the daydreams of her children as they looked out those windows to the sidewalks below? As I finished chalking at 116 Thompson Street, where Isabella had lived with her parents, I wondered if she had a fiancé or a boyfriend. Had she been setting aside her wages for a new life and a family of her own in America?

Last year, I returned to Thompson Street to Chalk the Tortorelli sisters with two young women. They both had an incredible grasp of Women's History and the role of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in the history of the United States. They set to work enthusiastically and smiled with pride as they noted that these two women, whose terrible deaths we now memorialized, had contributed directly to changes in New York labor laws, making them a model for the nation. They spoke about how the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire was a turning point in the life of Frances Perkins, the U.S. Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945. Perkins, they informed me, was the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet. She dedicated her life to improving working conditions after witnessing women jumping from windows to the pavement below. These events were a source of pride for this generation of women. It was a happy occasion with smiles all around and colored chalk memorials decorating the sidewalk.

Photo Credit: Kim Dramer

We remembered Isabella and Maria Tortorelli as women of courage and vision; women of determination, hard work and perseverance. Powerless sweatshop workers were now a source of pride and inspiration for this generation of women.

Through Chalk, for one day each year, until spring rain washes the chalk from the sidewalk on Thompson Street, the lives of these women are part of our city again. They touch a new generation of women. Their hopes and dreams live again in the sound of footsteps, walking over colored chalk, on the sidewalks of New York.

Photo Credit: Kim Dramer