I devoured these three books in the space of a week -- all about strong women doing outrageously difficult things against harsh and stunning landscapes. Reading these in tandem will drench you in a world of vast dry vistas, ranching, and barbed wire.

Stilwater, a memoir by Rafael de Grenade (Milkweed Press, 2014)

At age 24, Rafael de Grenade is dropped off at a remote corner of northern Australia to spend a dry season mustering cattle. Incessant mosquitos are the least of the critter worries; there are poisonous snakes and crocodiles. But this is no prison sentence; de Grenade is here by choice, in search of someplace wilder, more remote, than she has known before.

The work itself leaves many injured -- thrown up against fences, pressed there by feral bulls --sliced, mangled or busted fingers, ankles, feet and hands are commonplace. The work goes on.

I helped with the smashing and snaring and tumbling and tying of those massive animals, until I lost count in the madness... my heart throbbing, the sweat of nerves as I wrapped my hands around the leather straps and pulled the legs of the bulls to be tied. I came close enough to get covered in their snot, to feel the daggers of their eyes and dodge their huge horns.

What impresses me most is the co-existence of de Grenade's encyclopedic knowledge of her subject -- this piece of Australian Outback -- and her gift for poetic description.

In the stillness, beans dangled from the acacia trees, crows perched in the branches, and as night plummeted, mango leaves turned pale maroon on the branch tips. A blue-winged kookaburra ate a snake in silhouette against the sundown. Flocks of bright green budgerigars etched the teal sky, the little parrots sweeping through the gum trees long-leaved and faintly blue.

Because the author chooses to focus more on place than person, Stilwater pushes the boundaries of memoir. It's a beautiful piece of reportage--immersion journalism at its best. Ironically, it is how little de Grenade shares about herself that tells us the most about her.

On Stilwater, I did not have enough energy to love all that needed love; I could only give what compassion I could summon and observe the rest. I was ...quick to exclaim at beauty--wedge-tailed eagles flying, a low sun on bronze grass. But brutality was never far behind.

In this expanse, the gift of compassion dissolved in a flood of need.

This contemplation of compassion and its place in the outback, tells us about this narrator's priorities and perspective. She knows that place was and always will be first. That place has its way with us and we humans should honor that for the infinitesimal time we are here.

Where the Crooked River Rises, essays by Ellen Waterston (Oregon State University Press, 2010)

I love a book that leaves me altered -- that sidles up to my own experience via a terrain and occupation completely foreign to me. After reading such a book I understand my own life better. I burst into the other room to read some brilliant passage aloud to my husband. In Where the Crooked River Rises, Ellen Waterston gives us portraits of places and people, while synthesizing for us a local, practical wisdom and philosophy.

From the essay "PauMau," comes this collective portrait of the women who gather once a month:

...they can open and close the door with a simultaneous pull and swing, with the matter-of-fact agility of someone who has done lots of hard physical work, known hope, and weathered heartbreak, wielded a branding iron or vaccine gun, waved their husband through countless gates, cradled a colicky child, ridden the buck out of a mare, forgiven a drunk spouse...

From "Blue Bucket Gold," these bits of earned wisdom:

We were young enough to still think a whim was a factual survey.

This high desert, it seemed, wasn't much impressed by man's monuments to himself, tended to take itself back.

While most of these essays focus on the places and people she aims to articulate, Waterston occasionally lets readers in on her own hopes and heartbreaks.

I never was one for the realistic appraisal of things. ...fantasies about my husband, our marriage, and ranch life together.... I never anticipated, was not prepared for the fact that things could turn out badly, that the possibility even existed. And I came late to realizing that investing my energy in the fact they had in some ways turned out badly was not the best use of my energetic dollar...

I'm now a person of amalgamated faith. Despite everything, my sails are full.

Advice from this book that will stay with me:

...go like beautiful, exquisite hell in the time you have. Because in the end...nothing matters except the one hundred percent of the right now.

And Don Kerr's motto that I've now adopted:

The main thing is to keep your main thing your main thing.

Brilliant in its simplicity.

Waterston admits to hypocrisy in her own thinking, with essays like "Cows Kill Salmon." She admits to her own dreams gone bust in "Church of the High Desert." Every essay in this collection immortalizes something; as writers, we can't aspire to much more than that.

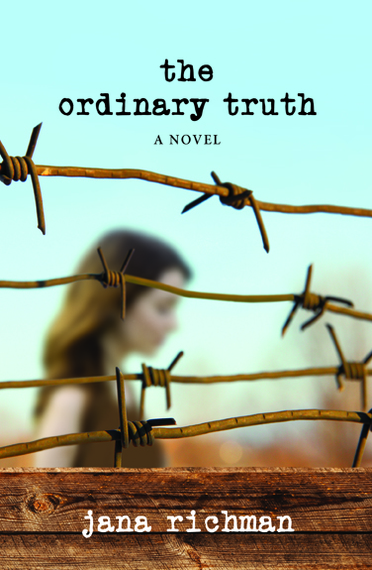

The Ordinary Truth, a novel by Jana Richman (Torrey House Press, 2012)

Fences feature prominently in all three of these books, but the cover art of Ordinary Truth puts barbed wire front and center, both close up and intentionally blurry. You don't realize how smart, artful and evocative this cover is until after you've read the book. By blurring the scene in the far distance, we see only smudges and heights, dust and lights, indications of a terracotta landscape. By keeping it suggestive rather than specific, the landscape can represent any era. Similarly, the soft edges to the young female's face allow her to stand as any of the female characters. She could be Cassie, the young Nell, or the young Kate, and this matches one of Richman's strengths as a writer -- her ability to ascribe equal importance to each woman's unfolding narrative.

Even Leona, Nell's sister-in-law, is given ample air time, and serves as an unbiased observer, an ever-present pair of eyes and ears, a heart, a surrogate, a Greek Chorus of commentary on the unfolding drama. We trust her take on things. Whether we are hearing Cassie's voice, from her summer job at the whorehouse, Wild Filly Stables, or her mom Kate's voice, from her high-powered job at Nevada Water Authority, or her Grandma Nell's voice back in Spring Valley, the authorial investment is the same. We're not meant to side with one more than the other. And as unlikable as Kate comes across, as bitter and closed up as a green pine cone, Richman gives her enough texture that we trust she has reason to be bitter.

But the barbed wire represents more than the ranching life and the sad boundaries family members erect between themselves. It harkens back to Kate's most potent memory of her dead father -- a day he was tightening a fence and the taut wire snapped and the young Katie was too close, right in its slicing, slingshot path.

I must have stopped screaming as soon as he picked me up. The only sounds I remember are his running footsteps--fast and hard on the packed earth--and his voice--deep and soft. I had no idea what had happened, but I wasn't afraid; my father had hold of me.

The scar she wears on her cheek is as indelible as the man himself--Henry Jorgensen, the book's most lovable character.

Toward the end of Ordinary Truth, after lies and secrets, grievances and resentments have been levied, Cassie expresses that "[t]he ritualistic nature of ranch work seemed the most likely path to healing." This could not be a more fitting conclusion to draw from all three of these books. The ritualistic nature of ranch work, the path to healing. There are always fences that need mending.