As a serial entrepreneur, I'm in the business of innovation. An entrepreneur constantly looks for market opportunities, or the aspects of life that frustrate us and prevent us from living and working at our full potential. Then the entrepreneur brings together a passionate team of people to invent a better way of doing things. If they're right about the opportunity -- if the frustration is great enough -- and they build the right team with the right culture and everything else falls into place, then a new venture is forged and seemingly overnight people can't remember how they ever lived without the venture's wonderful new product or service.

Look around our country today. I see an incredible amount of frustration. The institutions that define America aren't working anymore. And by institutions I mean the organizations, market structures, and social norms that determine the way that we live, work, and govern. This includes the corporations that provide us with goods and services, the way that we educate our children, the way that we manage our health, where our food, energy, and information comes from, the way we manage our resources, the way we elect our representatives, and the way our government works.

But don't take my word for it. Let's dig into the data.

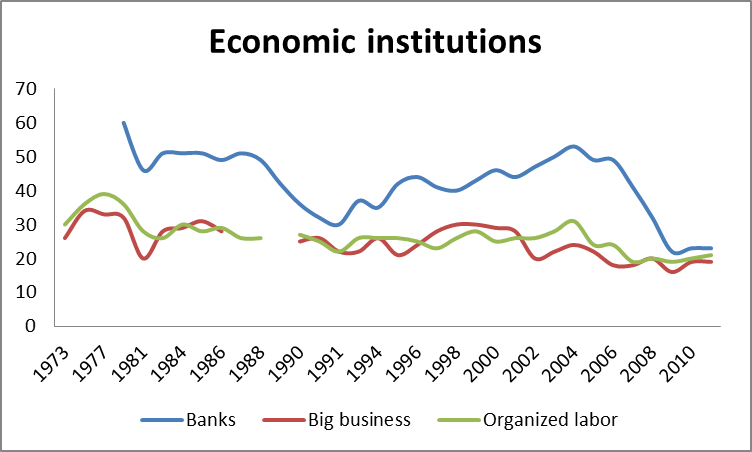

Based on polling data from Gallup, we've been getting more and more frustrated over the past 35 years but our anger has really gone from simmer to boil during the past few years and become a profound crisis of confidence. For example, in 1979, 60 percent of Americans expressed confidence in our banks, 32 percent in Big Business, and 36 percent in organized labor. While that's hardly resounding confidence, it's worlds better than last year when barely 20 percent of Americans had any confidence in any of them.

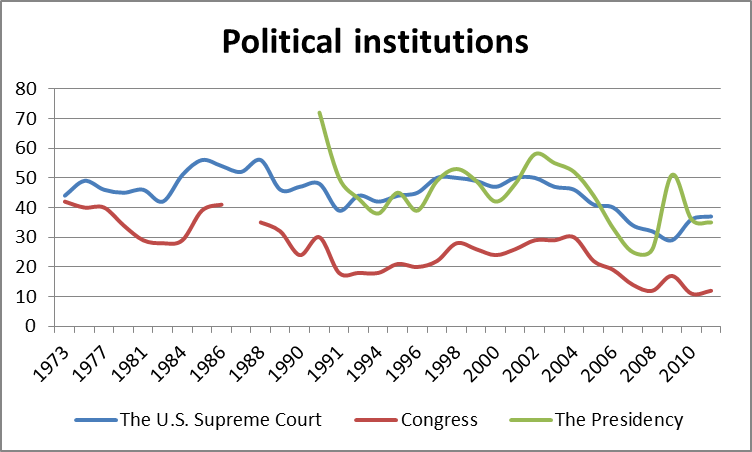

The same trend has held for our political institutions. In 1975, a year after Nixon resigned in disgrace, 52 percent of Americans had confidence in the Presidency as an institution, 40 percent in Congress, and 49 percent in the Supreme Court. Again, while these weren't stellar numbers, they're wildly better than 2011, when 35 percent of Americans had confidence in the Presidency, 37 percent in the Supreme Court, and an almost unbelievable 12 percent of Americans expressed confidence in Congress as an institution.

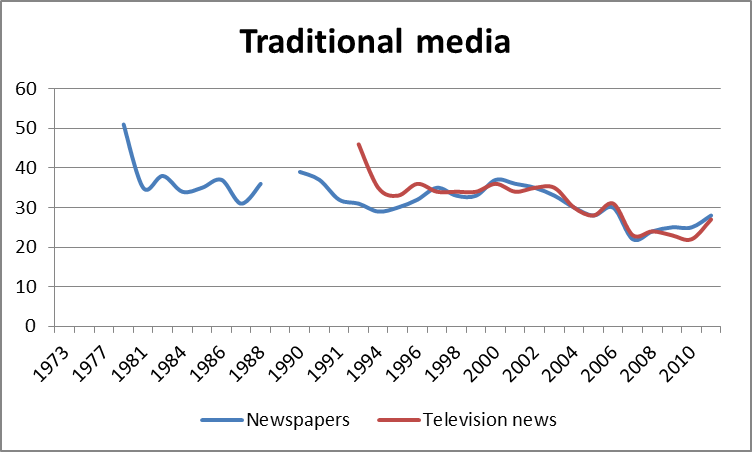

If you look at our traditional media, the pattern continues to hold. The last five years have seen the lowest sustained levels of confidence ever in our traditional media, with less than a quarter of Americans expressing confidence.

These patterns persist across other areas that Gallup has measured for a while. Through the late 1980s, around half of Americans consistently expressed confidence in our public schools. Over the past five years, barely a third feels the same way.

In fact, the only institution that has retained high levels of confidence over time is our military.

Gallup doesn't measure our confidence as a country in other institutions such as our universities, agribusiness, or political parties but I strongly suspect you'd see the same trends. This loss of confidence in the institutions that define the way we live, work, and govern is supported by other data sources. More importantly, if you look around American today, you can feel this palpable anger that things simply aren't working anymore.

The cause of this loss of faith isn't that these institutions have become less effective or less well intentioned. By and large, our institutions today are incrementally evolved versions of the institutions that we created before, during, and after World War II to organize a country that had suddenly become massively complex and industrialized. These institutions were designed to mass produce, mass market, and share risk -- with layers and layers of bureaucracy to move information from the bottom of the pyramid to the top and transmit decisions from the top back down to the bottom. They produce, we consume. We work, they insulate us from risk. At its core, this has been the implicit promise of America for the past 60 or 70 years -- whether between a corporation and consumers, between a media outlet and readers or viewers, or between government and citizens.

The institutions haven't changed much, but we have -- with radically greater expectations as individuals. Technology has empowered each of us with ready access to incredible knowledge and -- more importantly -- the ability to connect and collaborate with anyone and everyone. A single individual has never been more powerful. As we've become increasingly aware and empowered, we've also come less willing to defer to large bureaucracies that previously controlled information and the ability to mobilize resources. We now live in a world where one motivated individual can topple giants.

This transformation in the power of the individuals has profound consequences for America's economic and national security. Each of us is competing with every other intelligent, motivated person in the world for our economic prosperity and security. The winners will be the ones operating within a culture that values both individual freedom and the collaborative power of community, with institutions aligned to support individuals and communities rather than command and control them.

For America to lead, we have to reinvent our system and celebrate rather than fear the rapid shift from a culture of consumers and workers to a culture of entrepreneurship and collaboration.

My journey as an entrepreneur has taught me about the importance of culture in any venture. When there is misalignment between the expectations of your team, the culture of your venture, and the structure of your business, you will fail, no matter how great your market opportunity or brilliant your team. But I learned the incredible importance of culture before I ever started a company.

As I shared last week, I was kicked out of two schools in four years before I ever got to high school -- mostly for questioning authority. After getting booted out the second time, my parents drained their savings account to send me to seventh grade at a hippy alternative school. While I was there, I read about the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, a new magnet high school that had opened in Fairfax County. In order to apply I had to return to public school. Despite my checkered history, Jefferson miraculously accepted me.

I have no way of knowing if the actual education at Jefferson was better than what I would have received elsewhere. For me, however, the culture meant everything at Jefferson. It was cool to be smart and you were encouraged to show it. I still only graduated with a 2.6 GPA, but I learned an incredible amount, mostly from the other kids who also read voraciously and wanted to sit around talking about how the universe works.

While the academic culture was supportive, the experience that truly taught me about culture and leadership was rowing, which had only started at Jefferson three years earlier. Entering my junior season, we had a new coach, Eric Rothstein, and a group of seniors who were all excellent athletes in other sports. I was one of only two juniors in the boat and we entered the season with high expectations. It was a disaster. By the end of the season, few of us could stand each other and we were ecstatic to make it to the finals at the regional championships and not finish dead last. We had a "me" culture.

When the season was over, I was elected as one of two captains. Eric and I talked about what was broken with the team: We needed to completely reinvent our culture if we were ever going to win big. We needed to go from "me" to "us." He challenged me to sell the culture of us to the team. It was the first time anyone ever challenged me to be a leader and coached me that leadership meant creating the right culture.

My first foray into team building was my first lesson in entrepreneurship. Without a road map I did what I thought was best, organized the team and put structure in place. We didn't have many natural athletes left on the team, so we focused on the gawky kids who had never excelled at sports before, but were successful in the other parts of their lives because of their hard work, stamina and dedication.

By the time the season began, the 10 guys in competition for the top boat were all stronger and faster than any of the natural athletes had been the year before. We trained in complete silence while on the water. The other teams would goof around on the docks but we built our pride in our calm stoicism.

By regionals, we were convinced that we were going to win. With 500 meters left in the final, however, we were far out of the medals. Our coxswain called for one last sprint right as we heard the roar of the crowd at the finish line. We put everything we had into it, the boat felt like it flew completely out of the water, and we started closing the gap at a furious pace. When we crossed the finish line, we were in third, just off the first and second boats.

The most pride I've ever felt as a leader is when we got back to the docks. The rest of the team was there to celebrate, as we were the first men's eight in the history of Jefferson rowing to win a medal at regionals. What made me so proud though wasn't the celebration but the fact that every one of the guys in the boat was furious about losing. We had changed the culture of the team from relief at not finishing last to fury at not winning it all. While I never won gold at Jefferson, the men went on to win gold the next year and in fact 13 of the next 16 years. They've also won multiple national championships over the last decade and are now regarded as one of the finest high school rowing programs in the world.

Despite my atrocious grades, I was recruited to row at most of the Ivy Leagues, which only reinforced my suspicion that most everything my guidance counselor was telling me was wrong. Then, a month before the end of my senior year, I decided not to go to college.

When we arrived at Jefferson our freshman year, we were all told that if we did what we were supposed to do then we would get into the finest universities in the country. Even as a freshman, I wondered what came next. Would we get jobs at the finest corporations in the world? And then eventually become senior management, retire, and die? For whatever reason, going to college at that point in my life felt like I was accepting pre-defined limits on who I could be. At 18 years old, I decided to jump off the path that everyone assumed I'd take and become an entrepreneur.